Aquia Episcopal Church, Stafford, VA Established 1667

Aquia Church definitely is the type of Church that grabs our attention. It’s architecture, its history, and its cemetery all stand out as exceptional examples of early Virginian churches, those of Northern Virginia and specifically Stafford County. Being within an hour’s drive we have visited here numerous times, and none have disappointed us. Its history is intertwined with such notables as George Washington, Lawrence Washington, George Washington’s elder half-brother who owned the nearby iron-works Accokeek Furnace, George Mason, who grew up attending Aquia Church, as did his father and grandfather, Bishop William Meade, the Reverand Henry Wheeler, a well-known abolitionist, and many other prominent members of the early Aquia community.

Early Church History in Stafford County

Prior to the organization of Stafford County in 1664, the land forming Stafford was part of a larger Westmoreland County. When Westmoreland County was formed in 1653, the uppermost Church of England parish therein was called the Potomac Parish. This area included the land that extended from the juncture of the Machodoc Creek and the Potomac River, up the Potomac to the falls. No definite boundary was defined on the west, but it extended naturally in this direction as settlement moved further and further west. When Stafford County was formed in 1664, it included all of the region described as the Potomac Parish. At the same time, however, Potomac Parish was divided into two parishes, called the “Upper Parish” and the “Lower Parish. Over time the Upper Parish became known as Stafford Parish, and then again in 1702 as Overwharton Parish, while the lower parish became known as Chotank Parish, and then St Paul’s Parish. In 1777 when the boundaries of Stafford County were redefined, the area of St Paul’s Parish was added to King George County. After 1777, Stafford County consisted of a single parish, Overwharton Parish.1

The history of the churches of Stafford County is naturally closely interwoven with that of the county organization. Some of the very early records of the county, which were taken away during the Civil War, were found in the New York State Library, and restored to their rightful place within late years. From these the earliest acknowledgment of the establishment of Aquia Church can be found: 2

“April 3d, 1667. The Court doth order that the minister preach at three particular places in this county—viz.: At the southeast side of Aquia and at the Court House, and Chotanck, at a house belonging to Robert Townshend; to officiate every Sabbath Day in one of these places, successively, until further Order.” 3

This was the first of three known churches to be built on the present site of Aquia Church. Around 1700, this early structure burned and was replaced with a small wooden chapel.

In June of 1751, the Vestry of Overwharton Parish advertised its intent “to build a large Brick church, of about 3,000 Square Feet in the Clear, near the Head of Aquia Creek, where the old Church now stands.” On 6 June 1751 the Virginia Gazette carried the following advertisement:

“The Vestry of Overwharton Parish, in the County of Stafford, have come to a Resolution to build a large Brick Church, of about 3,000 Square Feet in the Clear, near the Head of Aquia creek, where the old Church now stands. Notice is hereby given, That the Vestry will meet at the said Place, to let the same, on Thursday, the 5th Day of September next, if fair, if not, the next fair Day. All Persons inclinable to undertake it are desired to come then, and give in their Plans and Proposals.”4

Mourning Richards, a local builder, “gave in” the winning proposal to the vestry. Following the practice of the time, Richards used his own money to defray the costs of construction as they occurred. The vestry, meanwhile, levied a special assessment on parishioners and paid Richards periodically in tobacco; it withheld most of the payments until he completed the project. Richards hired William Copein, a stonemason who later constructed Pohick Church (NRHP 1968), in Fairfax County, to lay up the walls and carve the doorways and quoins of Aquia Creek sandstone.

The church was more than three years in the building and was nearly finished when an accidental fire destroyed all but the walls. The Virginia Gazette reported the disaster on 21 March 1755:

“We hear from Stafford County, that the new Church at Acquia, one of the best Buildings in the Colony (and the old wooden one near’ it) were burnt down on the 17th Instant (17 March 1755], by the Carelessness of some of the Carpenters leaving Fire too near the Shavings, at Night, when they left off work. This fine Building was within two or three Days Work of being completely finished and delivered up by the Undertaker, and this Accident, it is said, has ruined him and his Securities. 5

The fire lay a heavy financial lost for Mourning Richards, however Richards finished the task by the spring of 1757.

The Disestablishment of the Episcopal Church in Virginia

After the Revolutionary War and the social, political, and religious uprising which followed the war, many Episcopal church structures in Virginia were abandoned and pillaged. In 1779 when Thomas Jefferson became governor of Virginia, he quickly proposed a “Statute for Religious Freedom”, which declared that no person should be required to support or attend a church or be punished or fined for his religious beliefs. He declared that:

“All men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in

matters of religion, without their civil capacities being in any way affected.”6

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison encouraged the legislature to repeal the laws requiring attendance at the established church and forbidding different religious practices. Repealing these religious laws encouraged the rise of Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians and other denominations in Virginia. Each of these religious denominations appeared in Stafford County in the mid- to late eighteenth century and exerted an influence on the religious composition of the county. 7

The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom was drafted by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the General Assembly on January 16, 1786, before being signed into law three days later. The statute affirmed the rights of Virginians to choose their faiths without coercion; separates church and state; and, while acknowledging the right of future assemblies to change the law, concludes that doing so would “be an infringement of a natural right.” Jefferson’s original bill “for establishing religious freedom,” drafted in 1777 and introduced in 1779, was tabled in the face of opposition among powerful members of the established Church of England. Then, in 1784, a resolution calling for a tax to support all Christian sects excited such opposition that James Madison saw an opportunity to reintroduce Jefferson’s bill. It passed both houses of the General Assembly with minimal changes to its text. One of the most eloquent statements of religious freedom ever written, the statute influenced both the drafting of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the United States Supreme Court’s understanding of religious freedom. Jefferson considered it one of his crowning achievements and a necessary bulwark against tyranny.8

This law “repealed every law which in any way favored the Protestant Episcopal Church in Virginia, totally disestablishing it” and in December 1801, the Assembly enacted a law empowering the Overseers of the Poor to “seize glebes and endowment funds of land purchased by the Episcopal Church prior to January 1, 1777” where no rector was active.9 This meant that glebes, which were at the time, the main source of income for rectors, would be seized once a rector of the parish died or left and churches could be seized if a “parish proved unable to maintain regular services in them.” 10

The Effect of Disestablishment on Aquia Church

As no form of governmental aid remained in place, disestablishment proved fatal for many churches in Virginia and Stafford County. Two church sites, Potomac Church, and Aquia Church, remained from the pre-Revolutionary period in Stafford. Constructed in 1664, Potomac Church was the first church in Overwharton Parish and one of the largest in Virginia at that time. Descriptions indicate that it was a rectangular building built of brick and covered with a hipped roof.11 Aquia Church was formed before 1680. Sometime before 1700, Aquia Church burned down and “was replaced with a small wooden chapel.”

Because of Disestablishment Aquia Church was swept up with the times. Disestablishment, in combination with other factors, would prove fatal to many churches. While the Church of Virginia was never formally subservient to the Church of England, its traditional association would give it a loyalist tinge. This does not appear to be the case here. Aquia’s minister, for instance, the Reverand Clement Brooke, embraced the revolutionary cause as a member of Stafford County’s Committee of Safety.

Other elements, however, would contribute to the decline of Aquia Church and Overwharton Parish. The rise of dissident faiths, and the spiritual emphasis of the “Great Awakening”, caused a loss of membership. Parishioners increasingly refused to both attend and support the Church. This was the same time that the soil depletion and movement toward the frontiers caused the population to drop. Stafford County recorded a gradual but steady decline in population during the first half of the 19th century.

Aquia Church suffered drastic membership losses due to these factors. Yet there was a revival to come. Bishop William Meade wrote in 1857 of the contrast between visits he paid to the church in that year and two decades earlier, when he beheld the churchyard which in other days had been filled with horses and carriages and footmen, now [1837 or 1838] overgrown with trees and bushes, the limbs of the green cedars not only casting their shadows but resting their arms on the dingy walls and thrusting them through the broken windows. . . . [In 1857] had I been suddenly dropped down upon it, I should not have recognized the place or building. The trees and brushwood and rubbish had been cleared away. The light of heaven had ‘been let in upon the once gloomy sanctuary. At the expense of eighteen hundred dollars, [the church] had been repaired within, with- out, and above. The dingy walls were painted white and looked new and fresh, and to me it appeared one of the best and most imposing temples in our land. The congregation was a good one.

War Time History

Intertwined in the life of those living through the early days of Stafford County were the effects of three wars, the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812 and the Civil War. Following the Revolutionary War Stafford County remained quiet until the War of 1812. During the War of 1812 the British fleet was sailing to Washington for an attack and anchored for some time on the Potomac River close to the Stafford shore near Potomac Creek. They landed and marauded the site of Marlborough Point, which had served as a fishing village since the town and courthouse were abandoned in the late eighteenth century. The British troops located Potomac Church which they burned and pillaged. The walls of the church later fell, and the ruins were visible for years.12

After the War of 1812, Stafford County enjoyed a peaceful existence until the Civil War. When the Civil War began, Stafford immediately became a large camping ground, and throughout the whole war troops from one army or another occupied its soil.13 Even though no major battles were fought on Stafford County soil, the Civil War was a staging ground for both the Confederate and Union armies. For the Confederates it was a defensive line. For the Union it was a key point in the Union Army’s move on Richmond.

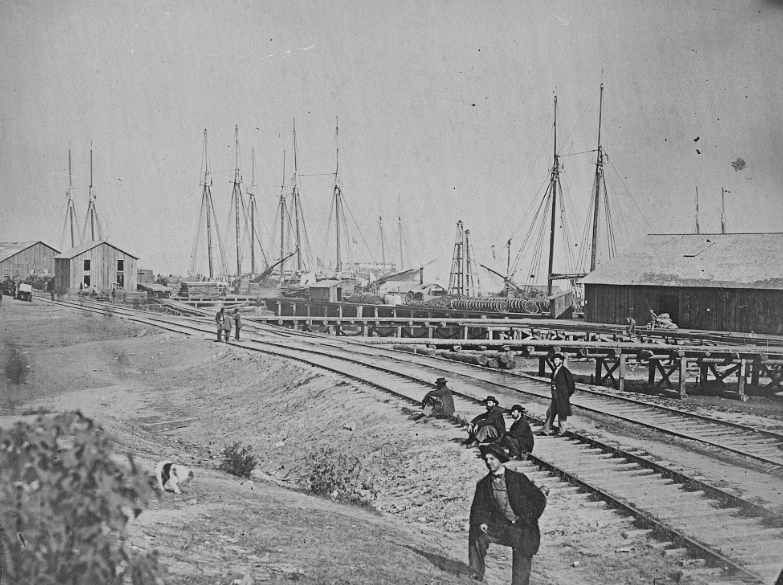

After the battle of First Manassas in July of 1861 the Confederates developed a defense line across Northern Virginia anchored at Aquia Creek in the east and Harpers Ferry in the west. By early summer 1861, the Confederate Army occupied Stafford in great force. To the Union Army it was obvious that there was a strategic importance to Aquia Landing’s location on the Potomac River as a port, coupled with its access to the Richmond, Fredericksburg, Potomac Railroad. This would make it an important supply base for the Union army and as the war progressed it would become such. Food, clothing and other equipment would be shipped down the Potomac River by the Union, unloaded there, and sent to the front by train. It was obvious to both armies that Aquia Landing had strategic importance for the Union army in reaching Richmond. This led to the first clash of the armies referred to as the Battle of Aquia Creek.

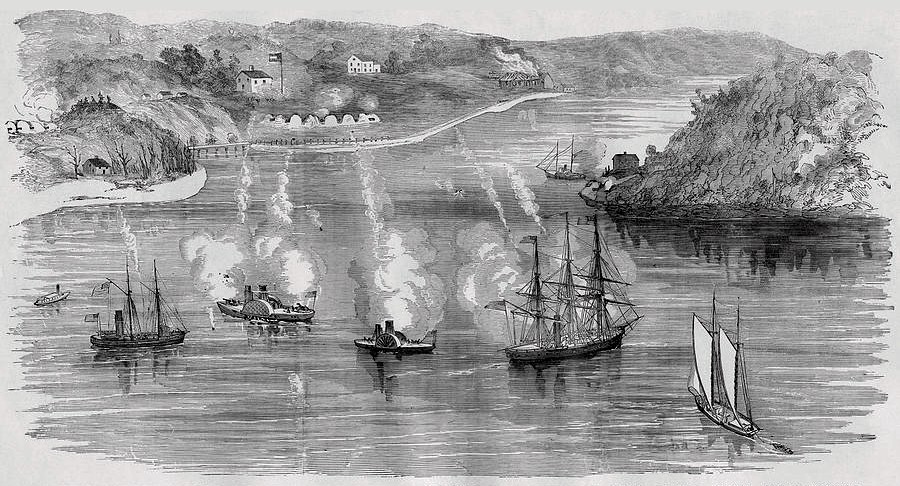

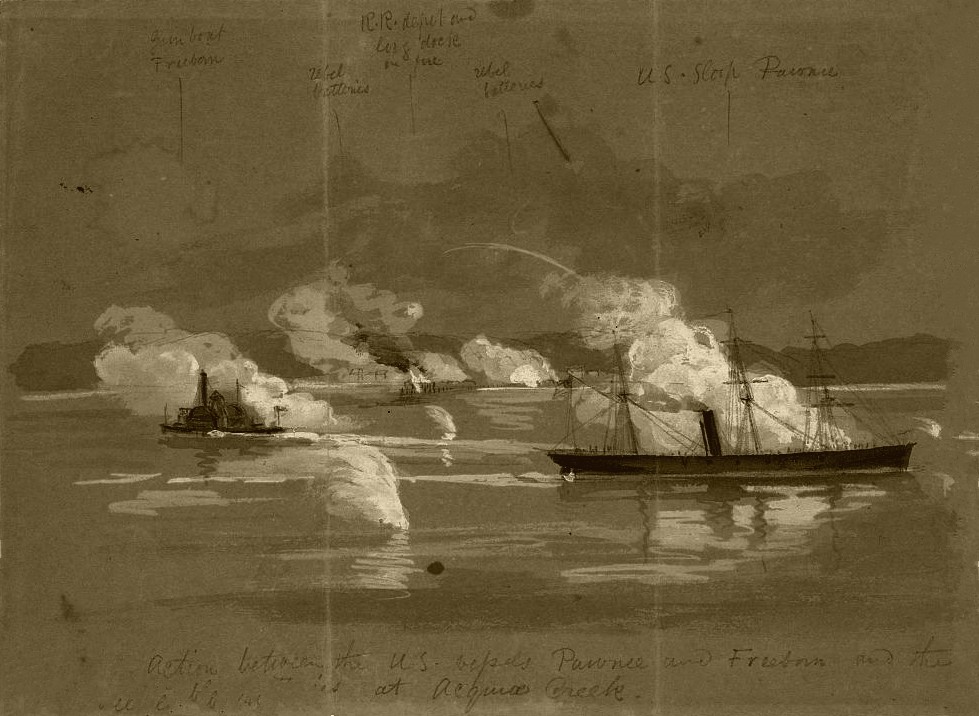

The Battle of Aquia Creek was an exchange of cannon fire between Union Navy gunboats and Confederate shore batteries on the Potomac River at its confluence with Aquia Creek. The battle took place from May 29, 1861 to June 1, 1861. Because of the Confederate defensive line was firmly established they were able to set up several shore batteries to block Union military and commercial vessels from moving in the Chesapeake Bay and along the lower Potomac River as well as for defensive purposes. Their battery at Aquia also was intended to protect the railroad terminal at that location. Knowing the strategic importance of the railroad and ship landing the Union forces sought to destroy or remove Confederate batteries as part of their effort to blockade Confederate States coastal and Chesapeake Bay ports. The battle was tactically inconclusive. Each side inflicted little damage and no serious casualties on the other. The Union vessels were unable to dislodge the Confederates from their positions or to inflict serious casualties on their garrisons or serious damage to their batteries. The Confederates manning the batteries were unable to inflict serious casualties on the Union sailors or cause serious damage to the Union vessels. The Confederates ultimately abandoned the batteries on March 9, 1862 as they moved forces to meet the threat created by the Union Army’s Peninsula Campaign.

It was during the winter months of 1861 and 1862 that the Union had devised a war strategy that involved an intensive assault on Richmond. One attempt at reaching the confederate Capitol included setting up a base at Aquia Creek. When the Confederate Army learned of the offensive, they destroyed the base at Aquia Creek, removed the cannon, burned the railroad ties and railroad bridges and retreated south.14 By the spring of 1862, Federal troops were rebuilding Aquia Landing for their own purposes while thousands of other Federal troops were moving through Stafford enroute to Richmond.

The Civil War’s Effect on Aquia Church

Over 100,000 Union troops would bivouac in Stafford for extended periods. The Church grounds were used both for encampment and for a hospital. The Church was occupied, as were most other buildings, and used as a stable. The pews were used as stalls, and the horse’s gnawing or “cribbing” on the pews necessitated them to be shortened after the war.

There is an account of Confederate soldiers holding a service in the church. An elderly Stafford resident told a Union chaplain of the 17th Pennsylvania Calvary that “a chaplain of a Tennessee regiment preached here and told his men in a few weeks he would preach to them from the steps of the capitol in Washington from the text, “Shout, for the Lord hath given you the city” (Josh. 6:16). 15

On November 8th, the 4th and the 5th Texas infantry regiments left for the Potomac arriving by train in Brooke Station, Stafford County sometime early in that month. 16 When they arrived, they joined with the 1st Texas and the 18th Georgia regiments to form a brigade known as the Texas Brigade.17 They would spend their winter camp in the area, patrolling from Dumfries to northern Stafford. By April 3rd of 1862, Nicholas A. Davis, a chaplain for the 4th Texas regiment noted “Acquia Church, the headquarters of the Texans.” 18

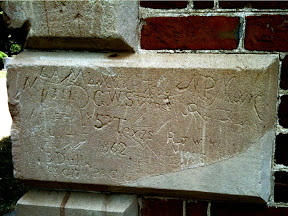

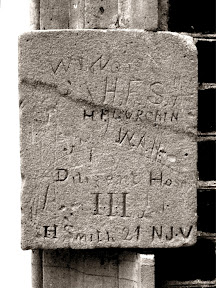

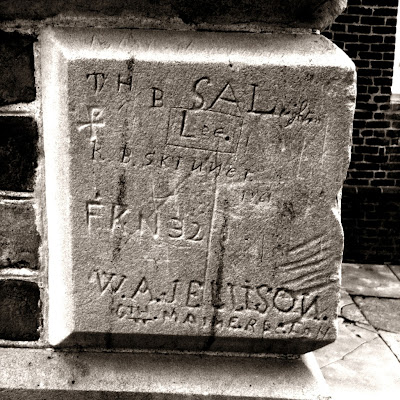

While the Confederates occupied Aquia Church the following soldiers left their names on the walls for posterity.

- Charles McCally of Company F, 5th Texas Infantry

- Benjamin Wickliffe Bristow of Company C, 5th Texas Infantry

- George W. Starnes of Company F, 5th Texas Infantry

- George Julian Robinson of Company A, 5th Texas Infantry (who carved only his initials, GJR)

The 17th Pennsylvania Calvary Volunteer Regiment also used the church for its intended purpose. “During our short stay [in February of 1863] at this beautiful spot several religious services were held in this church in charge of our Regimental Chaplain, Rev. Henry Wheeler”, apparently to overflow crowds of unit members. This Rev. Wheeler, a minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, took quite a liking to Aquia Church and was put in charge of the guarding troops.

The attitudes of the Church’s occupiers varied upon their view of the War. David W. Judd, “New York Times” correspondent, describer Aquia Church as “an interesting relic of the old-time Aristocracy, concerning which the present race of Virginians boast so much, and possess so little.” He writes of the presence of a fresh grave outside the door adjoining three old graves, containing the body of “Henry Basler, Co. H, 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers.” Other troops were also buried on Church grounds as the locals, studiously friendly by day, were equally dangerous by night. Judd further notes, without remorse, the desecration of a tombstone and grave.

During the occupation of Aquia Church the following Union Soldiers left their names on the walls for posterity.

- Charles Wilson Van Epps of Company A, 9th New York Cavalry

- Benjamin Dull of Company G, 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry

- Peter Pass of Company G, 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry

- H. Smith of the 21st New Jersey Infantry (there are 3 possible authors of that graffiti, Henry, Henry C. and Humphrey)

- William Albert Jellison of Company H, 6th Maine Infantry

Architectural Analysis taken from the National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet DHR File 89-8

Aquia Church sits on a heavily wooded hilltop at the northeast corner of the intersection of us Route 1 and VA State Route 610, about thirteen miles north of Fredericksburg, Virginia. Reached by a steep, curving drive, the church and its cemetery are located in a clearing enclosed by a nineteenth-century iron fence.

Constructed of brick laid in Flemish bond with random glazed headers, the two-story Georgian church has a Greek cross plan with a tower and cupola on its western arm. The arms of the cross are each about sixty-four feet long and thirty-two feet wide. Among the structure’s original details are keystones, quoins, and door frames carved from Aquia sandstone quarried at nearby Aquia Creek. The quoins appear on all eight corners of the church, and are supported by concrete bases which replaced the original stone in 1915-1916. The church is set on a water table of brick laid in common bond, which replaced the earlier water table in 1915-1916. The base of the building is lined with a modern concrete ground gutter.

All elevations but that on the east have pedimented and rusticated door frames of Aquia sandstone; all the raised-panel double doors themselves are twentieth-century replacements based on those at Vauter’s Church. The design for the door frames may have been derived from plate XXIX in Batty Langley’s Builder’s and Workman’s Treasury of Designs (1750). An architrave molding surrounds each door and is interrupted by rustication at the sides and a splayed flat arch with a scroll-faced keystone at the top. On the western elevation, the flat arch is superimposed over the base of a simple pediment, while on the other elevations the pediment surmounts both the lintel and the flat arch. The word Aquia was carved in the tympanum of the western door sometime before 1930. The tympanum of the southern door is filled with the inscription, “Built/AD 1751 Destroyed/By Fire 1754 (sic) & Rebuilt AD 1757/By Mourning Richards Undertaker William Copein Mason.”

The first-floor windows on every facade have flat heads, while those on the second floor have arched heads. The original nine over-nine sashes remain in the first-floor windows, but the muntins have been replaced. The three windows on each end elevation of the second floor have rubbed brick, semicircular arched tops; the rubbed brick is of finer quality than on the first floor. Both the flat and semicircular arches over the windows originally consisted of alternating stretchers and pairs of headers. The side elevations of each of the arms of the Greek cross have one window on each floor, matching the windows on the end elevations. The three entrances to the church are flanked by windows with rubbed brick jambs and flat arches.

There have been many repairs to the brickwork, and the stonework has suffered from graffiti and other vandalism. Brick repairs can be seen around many of the windows, and many of the window frames have been replaced, along with the entire water table. Aquia stone is known for its softness and some visitors have carved their initials or names into the quoins at Aquia Church over the years. During the Civil war, for example, soldiers who occupied the church not only carved their names and units in the stone outside, but wrote all over the walls of the interior as well.

The exterior of the church evidently was painted before the mid nineteenth century, for Bishop William Meade noted when he visited the church in 1857 that the “dingy walls were painted white, and looked new and fresh” compared to when he saw them last in 1837 or 1838.19 Paint was cleaned from the walls sometime around 1930.

The horizonality of the western elevation is countered by the vertical thrust of the pedimented door frame and the peculiar pedimented tower above it. Only the west wall of the tower is brick, with quoins and a window matching those below in the body of the church. A belt course of stone runs across the west wall at the springline of the arch-topped window, and another runs along the base of the tower. The other three walls are frame sheathed in wood shingles. The tower rests on the hipped roof of the church, which has been clad in copper shingles for most of this century. The roof of the tower is cross-gabled, and the front gable is broken by the base of a small, square, conical-roofed cupola that presently is surmounted by a cross. A simple cornice with rectangular modillions appears at the eaves, both on the tower and on the body of the church.

The construction date of the tower is unknown. An 1857 illustration shows a ball finial instead of the cross, as well as a clock that fills the cupola. If the tower was intended for a clock, it may date from the early nineteenth century; of course, a clock could have been added later to a preexisting tower. Bishop Meade, in referring to his visit of 1837-1838, called the tower an “observatory,” which could indicate an earlier date of construction. One architectural historian noted that the stonework in the tower (quoins, belt course, baseboard, and keystone) appears to be nearly identical in quality and execution to that of the rest of the structure, which suggests that it was built at about the time.

Inside the church, the chancel fills the eastern arm of the cross. The eastern end wall–the only one without a doorway–has the same fenestration as the others, but an elaborate, original classical altarpiece fills the central space. A three-level pulpit topped by a hexagonal sounding board dominates the southeast crossing, and a handsome gallery provides a modern choir loft in the western arm. Much of the interior is original, and despite an abundance of austere white paint, the immediate impression is of a richness of detail.

The pedimented Ionic altarpiece frames four arch-topped tablets on which are painted the Ten Commandments (on two tablets), the Apostles Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. These tablets are of pine painted black–the rest of the altarpiece is painted cream–and are signed by the painter, William Copein. The pediment has a low slope, a modillioned cornice, and a raised panel within the tympanum. Two Ionic pilasters support the entablature of the pediment. The horizontal and vertical panels below each tablet are restorations that date from 1933 and are based on the originals. The communion rail and other altar furniture are modern.

Only six large pedimented architectural altarpieces survive in Virginia: Abingdon Church, Gloucester County, ca. 1755 (NRHP 1970); Aquia Church, Stafford County, 1757 (NRHP 1969); Christ Church, Alexandria, 1767-1773 (NHL 1973); Christ Church, Lancaster County, 1735 (NHL 1969); Little Fork Church, Culpeper County, 1774-1776 (NRHP 1969); and St. John’s Church, King William County, ca. 1734 1765 (NRHP 1972), the altarpiece of which was removed in 1984 to St. Paul’s Church, Norfolk, ca. 1739-1786 (NRHP 1971), Of these six, three have triangular pediments; those at Abingdon and Little Fork are broken while that at Aquia is complete.

The pulpit and sounding board rival the altarpiece for visual impact. The first level is the triangular clerk’s desk which, as with the other two levels, is entered up steps from the altar side. The sides of the clerk’s desk are sloped, so that the readings lie pitched toward the reader on the lectern. This has prompted one architectural historian to note that the whole pulpit resembles a ship’s prow.20 The clerk’s desk has a raised panel on each side that is visible above the enclosing pew and scrolls that connect it to the pew that supports it. The next level is the reader’s desk where the minister stood to conduct the service; except during the sermon. This desk is square and is set at an angle to the crossing, facing the opposite corner. Each of its sides has two raised vertical panels topped by smaller horizontal panels. A short staircase with turned vase-and-column balusters leads ultimately to the top level of the pulpit; the stair has a short spur that allows access to the reading desk. The pulpit itself is hexagonal, matching the shape of the sounding board above it. The pulpit has a vertical and a horizontal raised panel on each of its sides. The upper pulpit is supported by a hexagonal column which curves to meet the sides of the pulpit, echoing the ogival top of the sounding board above the pulpit. The sounding board has a gilded hexagonal star on the raised panel of its soffit, and a finial at its top. The back of the pulpit is framed by pairs of simple fluted pilasters. Only one other triple-deck pulpit survives intact in Virginia, at the 1735 Christ Church in Lancaster County (NHL 1969).

The gallery in the western arm of the church is supported by four slender fluted Doric columns set on tall plinths that reach more than a foot above the backs of the boxed pews. The paneled parapet of the gallery is divided by eight pilasters, four of which are paired. Within the center panel is a coeval dark wood tablet on which are painted the names of the minister and the vestry at the time of the construction of the church. There are two small, gilded, five-pointed stars within the side panels that may indicate a support system within the parapet of the gallery. The hand railing at the top is of dark wood, while the rest of the parapet is painted a cream color. The gallery is accessible by a stair that runs up the west wall of the church from the door to the north corner, then turns at a right angle and finishes its run up the north wall of the west arm of the church. It has turned balusters like those around the pulpit, and a dark wooden handrail. A modern organ and chairs now furnish the gallery, which is used as a choir loft.

All the pews are painted white, with a dark wood molding at the top, and all but the pew at the foot of the pulpit were cut down after the Civil War. The height of the original pew enclosure is defined by a vertical panel with a smaller horizontal panel above, while all the others are only the height of the vertical panel, the upper panels having been removed. The benches are arranged in au shape within the pews that range the arms. Those at the crossings are large, square enclosures with benches on all four sides, except for the one at the northwest crossing, which has a spine of benches down the middle as well as around the sides. The christening pew is under the gallery, north of the aisle. The marble baptismal font was donated in 1917.

A wooden floor, which may have replaced an earlier stone floor, was itself replaced after the Civil War. The present floor is of irregular cut sandstone. A white marble cross was placed in the floor at the crossing in the 1930s, and the floor of the chancel was replaced with marble at the same time. There are several graves under the chancel that were not marked when the floors were replaced. The walls still have their original plaster, which is painted white. There is a coved cornice at the top of the walls, and the church now has a flat plaster ceiling, which replaces a nineteenth-century wooden ceiling.

The tower room is reached by a stair from the gallery that ascends from the north corner against the west wall. The tower room is a small space (nine and a half feet by eleven feet) with a very high ceiling and unpainted matchstick paneling on all four walls and the ceiling. The tower and this room may have been added after the fire of 1755, and it is likely that the clerk kept his office here. The tower’s window is in the west wall and a door to the attic is in the east wall. The framing system is visible in the attic, dominated by a king post in the center.

The large cemetery is enclosed by a nineteenth-century iron fence. To the south of the church there are several eighteenth-century graves, some marked by table stones that were moved from nearby family cemeteries. The church cemetery is still in use. Southwest of the cemetery is a pair of noncontributing eighteenth-century frame houses that were moved to the site in 1988 and reconstructed as one building. The smaller one has a large stone chimney at its west end. Across the driveway from it is the noncontributing parish hall, a modern, T-shaped brick structure built on the side of the hill. Because of the slope, its southern end has two stories, but the northern end, which faces the church, has only one story. A semicircular, lightly wooded area fills the curve in the gravel driveway at the top of the hill, with a space for parking across from the cemetery.

Sarah S. Driggs

OVERWHARTON PARISH REGISTER

1720 to 1760.

OLD STAFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA

BY WM. F. BOOGHER

WASHINGTON, D. C. THE SAXTON PRINTING CO.

1899.

STAFFORD COUNTY, VIRGINIA

The County of Stafford and Parrish of Overwharton derive their names from the corresponding ones in England. The County of Stafford was erected in 1666 out of Westmoreland, extending to the Blue Ridge Mountains, being the frontier county, and was about twenty-four miles in width south and west of the Potomac River. It was first represented in the House of Burgesses by Col. Henry Mees, June, 1666. (Henings Statutes. Vol. 2, p. 250,) he being allowed 130 lbs. Of tobacco and a cask per day; traveling expenses at the rate of four days each way for his attendance as a member of the Assembly. If traveling by water, only 120 lbs. Of tobacco per day. (Mercer’s Abridgement, p. 39.) The county first appears among the proceedings of the Assembly as a county in June, 1675, when the Rappahannock, Westmoreland and Northumberland, Stafford was exempted from erecting looms and weaves, in consideration of the newness of the soil and the consequent inability to maintain them; this being more conducive proof of its establishment as a county than the mere circumstance of its being represented in the Assembly, as by the law then existing, any county which would lay out 100 acres of land and people it with 100 tithable persons should entitled to a representative in the Assembly, notwithstanding the Act limiting the number of two representatives for a county. (Hening, Vol. 2, pp. 238-39.)

This law was changed October, 1705, requiring 800 tithable persons necessary to erect a new County on the frontier. Stafford Court House was first built at Marlboro, on the Potomac, afterwards moved about 100 yards from the site of the present Court House, which was built in 1783-material, brick covered with stucco of mortar; main building 20×40, with a T wing 20×30; two acres of land for the Court House and Prison deeded in 1783 by William Gerrard and William Fitzhugh. The number of voters in the County in 1899 was 1725; 1400 white and 325 colored. Population of the village of Stafford Court House is 25, all white.

There are but few records of old Stafford County to be found in the vault of this ancient Court House until about 1699. Very many of those from 1699 to 1862 were either destroyed or stolen during the Civil War. Those that remain are indexed so that examiners have no trouble in searching.

OVERWHARTON PARISH

This Parish was co-extensive with Stafford County, covering a part of what was once Washington Parish, extending about eighty miles along the Potomac, in breadth about four and twenty miles, embracing with its territory what is now Prince William, Loudoun, Fairfax, Alexandria Counties and part of Fauquier until 1730, when Prince William County was taken from Stafford, and Hamilton Parish was erected, succeeding Overwharton as the frontier parish. Of the early history of Overwharton Parish and its rectors, but little is known.

In 1724, there were 650 families and about 100 communicants. One Church, Potomac (situated about nine miles south of the present Aquia Church), the brick walls of which were standing until torn down by the Federal army during the Civil War. It is, however, evident, from the number of white occupants of the soil within an area of ten miles, that there must have been frontier chapels of ease in the immediate locality of Potomac Church about 1675, if not a church. The Rev. Dr. Scott was rector as early as 1710, and continued until he died, April 1, 1738, aged 52 years, 9 months, and 20 days; he was succeeded by Rev. John Moncure, a Scotch gentleman, but of Huguenot descent, who acted as assistant or curator to the Rev. Mr. Scott for a short time previous to his death; Rev. Mr. Moncure continued as rector of the Parish until his death, in 1764. Of the old Potomac Church, there are no vestry records known to exist. The earliest records of members of the vestry of Overwharton Parish are those of Aquia Church, beginning in 1757. This church was first built in 1751, thirteen years after the death of Mr. Scott, and was destroyed by fire in 1754, and rebuilt in 1757 upon the original foundation, as charred remains are yet to be found under the church, and about the foundation.

An inscription over the door states as follows:

“Built 1751; destroyed by fire 1754; rebuilt 1757.”

And upon a panel on the gallery appears the following:

“John Moncure, Minister, 1757.”

VESTRYMEN

| Peter Hedgman | Benjamin Strother |

| John Mercer | Thos. Fitzhugh |

| John Lee | Peter Daniel, Warden |

| Mat Doniphan | Travers Cook, Warden |

| Henry Tyler | John Fitzhugh |

| William Mountjoy | John Peyton |

As to the successor of Mr. Moncure in this parish, it is probable that the Rev. Mr. Green took his place in 1764. In the years 1774 and 1776, the Rev. Clement Brooke was minister. After the Revolution, in the Convention of 1785, called for organizing the diocese and considering the question of a general confederation of Episcopalians throughout the Union, we find the Rev. Robert Buchan the minister of the Overwharton parish, and the Rev. Mr. Thornton, of Brunswick parish, which had been taken from King George and given to Stafford when St. Paul’s was taken from Stafford and given to King George. The lay delegates at that Convention were Mr. Charles Carter, representing Overwharton parish, and Mr. William Fitzhugh, of Chatham, representing Brunswick parish, which lay on the Rappahannock, and extended to Hanover parish in King George. In the year 1786, Mr. Fitzhugh again represented Brunswick parish; and this is the last notice we have of the Church in Stafford until some years after the revival of conventions. In the year 1819, the Rev. Thomas Allen took charge of this parish, preaching alternately at Dumfries and Aquia churches. At a subsequent period the Rev. Mr. Prestman, gave all his energies to the work of its revival. The labors of both were of some avail to preserve it from utter extinction, but not to raise it to anything like prosperity. The Rev. Mr. Johnson also made some ineffectual efforts in its behalf as a missionary.

Old Aquia Church stands upon a high eminence, not very far from the main road from Alexandria to Fredericksburg. In 1838 it was a melancholy sight to behold the vacant space around the house, which in other days had been filled with horses and carriages and footmen, now overgrown with trees and bushes, the limbs of the green cedars not only casting their shadows but resting their arms on the dingy walls and thrusting them through the broken windows, thus giving an air of pensiveness and gloom to the whole scene. The very pathway up the commanding eminence on which it stood was filled with young trees, while the arms of the older ones so embraced each other over it that it was difficult to ascend. The church has a noble exterior, being a high two-story house, of the figure of the cross. On its top was an observatory; which was reached by a flight of stairs leading from the gallery, and from which the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, which are not far distant from each other, and much of the surrounding country, might be seen.

After a visit made to the same church, about 1856, Bishop Meade says:

“I should have not recognized the place or building. The trees, brushwood and rubbish had been cleared away. The light of heaven had been let in upon the once gloomy sanctuary. At the expense of eighteen hundred dollars (almost all of it contributed by descendants of Mr. Moncure), the house had been repaired within, without and above. The dingy walls were painted white and looked new and fresh, and to me it appeared one of the best and most imposing temples in our land. The congregation was a good one. The descendants of Mr. Moncure, still bearing his name, formed a large portion.”

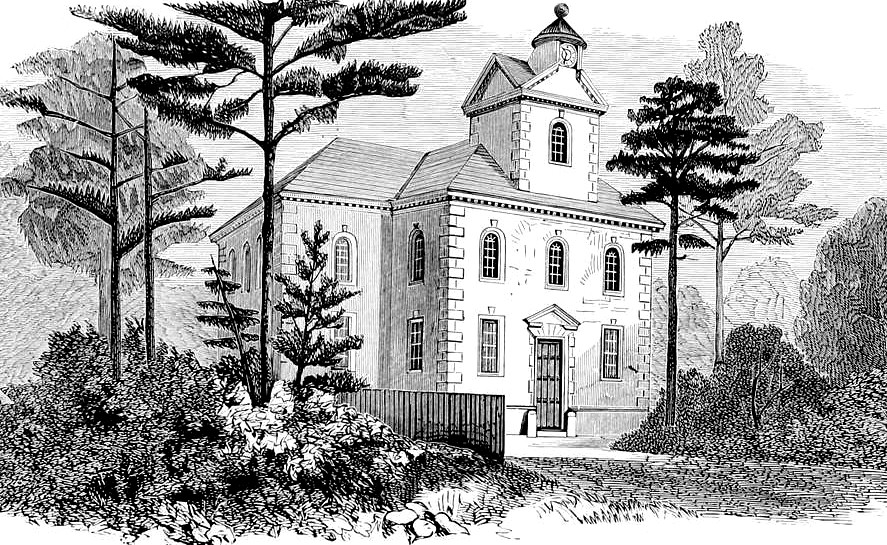

The following is the view of the church subsequent to the late Civil War, supplied by Messrs. Lippincott & Co., being from the same plate as the one used in “Old Churches and Families of Virginia,” by Bishop Meade, Volume. 2, pp. 197-206, to which publication I am indebted for a portion of this historical sketch.

About 1840 the church had fallen into decay and remained so, as stated by Bishop Meade, until about 1850, when Henry Wall took charge as minister. He was succeeded about 1858 by the Rev. Mr. Mackenheimer, who served until the Civil War, during which time the church was temporarily occupied by the Federal troops and, as a result was desecrated and defaced, for which a claim is now pending before Congress.

Shortly after the war the church was again repaired, largely by the assistance of Rev. J. M. Meredith and Hon. William S. Scott, of Pennsylvania, a descendant of Rev. Alexander Scott. Rev. Mr. Meredith then became rector, and in 1875 was succeeded by Rev. Mr. Appleton; in 1877 by Mr. Pruden; in 1878 Rev. Geo. M. Funsten; in 1884 by Rev. Thos. Cater Page, who remained until 1889. It was then vacant for two years, when Rev. John H. Birckhead became rector and remained until 1896. He was succeeded by the present incumbent, Rev. J. Howard Gibbons. The above dates are claimed to be nearly exact. Vestrymen before the war, not known, but the first vestry after was as follows:

| Gen. Fitzhugh Lee | Geo. V. Moncure |

| Wm. E. Moncure, Warden. | Hugh Adie |

| R. C. L. Moncure, Warden | N. W. Ford |

| Powhatan Moncure | E. A. W. Hore |

| Col. Thomas Waller | Benjamin A. Bell |

The present vestry is as follows, viz: (1899 when this was published)

| Jas. Ashby | Walter Bozzell |

| Powhatan Moncure | Sec’y and Treas |

| Hugh Adie | E. D. Moncure |

| Geo. V. Moncure, Jr. | Frank Blackburn |

| Geo. V. Moncure, Sr. | R. Minor Moncure |

| J. M. Ashby | Wm. P. Patterson |

| R. A. Moncure |

Number of families represented, not known. Present number of communicants, 80.

Wm. F. Boogher

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

INVENTORY NOMINATION FORM

ENTRY NUMBER 69-11-45-0055

Virginia SP Aquia Church – Stafford, Virginia

Aquia Church is a two-story brick structure with a hipped roof and an unusual and unique tower and cupola worked into the upper level of the entrance arm of the building. The exterior of the church is noteworthy for its fine stonework decoration which appears in the keystones of all the windows, the quoins of all eight corners of the building, and in the three pedimented and rusticated doorways. The walls are laid in Flemish bond with random glazed headers; rubbed brick appears in all the window jambs and arches. The modillion cornice on both the main part of the building and the tower is probably original. The windows of the first level have flat arches while those of the second level are topped by semi-circular arches. The sash of the first level windows is original although the muntins have been replaced; the sash of the upper level windows is a twentieth century restoration. Other twentieth century work includes the roof shingles and doors. The water-table has also been renewed.

The handsome interior of Aquia Church retains its original triple-tier pulpit, reredos, west gallery, and pews. The magnificent pulpit includes the reading desk, and the clerk’s desk, as well as the sounding board. The reredos is composed of four tablets separated by Ionic pilasters and topped by a pediment. Although the pews are original, all save the one immediately below the pulpit have been cut down. The wooden ceiling dates from just after the Civil War. The flagstones in the aisles are twentieth century, the originals having been removed to make the front walk and fill the old road to the church. The marble floor in the chancel dates from 1933. Although most of the later alterations detract from the building, none of them are irremediable.

One of two colonial churches in Virginia with a true Greek cross plan, Aquia Church was erected in 1751, with Mourning Richards as “undertaker” (contractor). William Copein, who also worked on Pohick Church in nearby Fairfax County, was employed as the church’s mason. The church was severely damaged by fire in 1754 and rebuilt in 1757. It is believed that the present walls date from 1751, and that the remainder of the fabric including the interior dates from the rebuilding of 1757. Services have been on or near the site of the existing building as early as 1654. The present church became the parish church for Overwharton Parish in 1757.

As it stands today, Aquia Church is one of the most elaborate, as well as one of the preserved of Virginia’s churches. It ranks as one of the more important examples of colonial ecclesiastical architecture in the nation. Its rich interior appointments are among the finest in the state; the magnificent triple-tiered pulpit is unique in Virginia.

Aquia Church is fortunate to possess its 1739-40 Thomas Farren communion silver. The silver was buried in the wars of 1776, 1812, and 1861-65.

Although located near a major highway in a part of the state that is rapidly becoming urbanized, Aquia Church, with its church yard and surrounding woods, still possesses a placid rural setting.

Other Early Churches of Stafford County

After the Revolutionary War and the social, political, and religious uprising which followed the war, many Episcopal church structures in Virginia were abandoned and pillaged. In 1779 when Thomas Jefferson became governor of Virginia, he quickly proposed a “Statute for Religious Freedom”, which declared that no person should be required to support or attend a church or be punished or fined for his religious beliefs. He declared that:

“all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in

matters of religion, without their civil capacities being in any way affected.”

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison encouraged the legislature to repeal the laws requiring attendance at the established church, and forbidding different religious practices. Repealing these religious laws encouraged the rise of Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians and other denominations in Virginia. Each of these religious denominations appeared in Stafford County in the mid- to late eighteenth century and exerted an influence on the religious composition of the county.

In the last half of the nineteenth century, as population centers were reaching further afield, a series of small chapels representing various denominations were built throughout the parish. Twenty chapels from the late-nineteenth to early-twentieth century were examined during the survey of the county. Listed below are some of the churches on that list we were able to find information on:

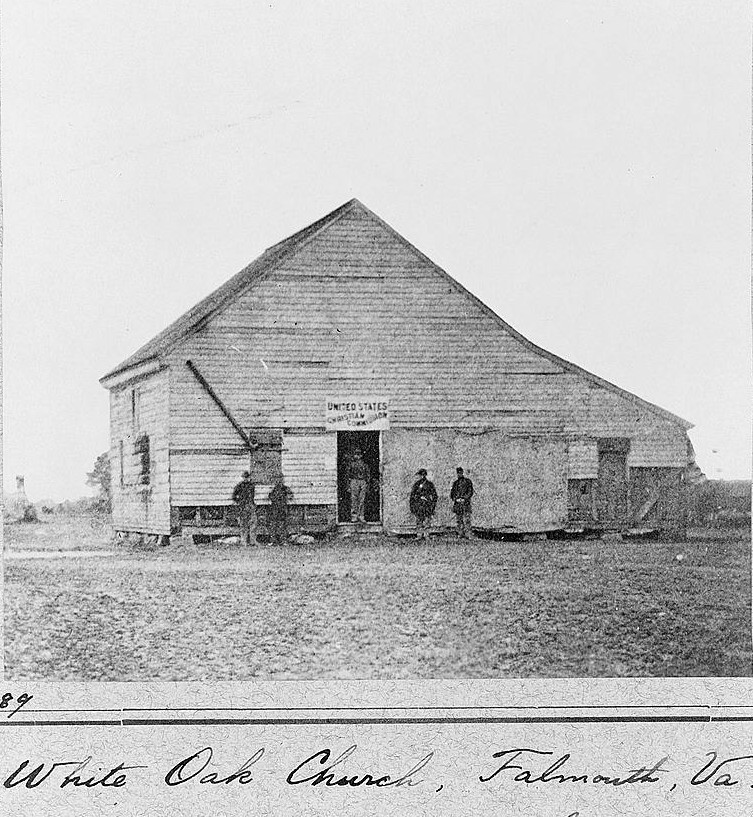

White Oak Church

White Oak Church, also known as White Oak Baptist Church and White Oak Primitive Baptist Church, is a historic Primitive Baptist church located off White Oak Road in Falmouth, Stafford County, Virginia. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.

Clifton Chapel

Clifton Chapel was a little white framed building in the Wide Water area of Stafford. Exactly when Clifton Chapel was constructed is uncertain. A diary kept by Nathaniel Waller Ford (1820-1880) of nearby Woodstock notes that in February of 1850 he had collected $15.50 for repairs to the chapel. Based upon construction techniques and this diary entry, the chapel may have been built in the late 1840s. The repairs undertaken in 1850 were completed by a local free black man named Barney Wharton (c.1792-after 1870), a carpenter who also built a new house for Nat Ford that same year.

Union Church and Cemetery

Union Church and Cemetery is a historic Episcopal church and cemetery located at Falmouth, Stafford County, Virginia. The property contains the archaeological sites of the 1733 and 1750s Falmouth Anglican churches and the standing remains of the Union Church, built about 1819. The Union Church narthex, measuring 10 feet by 40 feet, is the section remaining from the Federal style building. The building contains an original stairway to the balcony and framing that extends upward to form the belfry which supports an estimated 300-pound bell. Also on the property is the church cemetery with headstones, dating from the 18th and the early 19th centuries through the 20th century. A violent rain storm in 1950 severely damaged the roof of the 40 feet wide by 54 feet long church leading to a collapse of the chancel and nave, leaving only the narthex intact.

Hartwood Presbyterian Church

Hartwood Presbyterian Church was organized in June 1825 by Winchester Presbytery as Yellow Chapel Church, the brick church was constucted between 1857 and 1859. It became Hartwood Presbyterian Church in 1868. During the Civil War an engagement took place here on February 25, 1863. Confederate Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, commanding detachments of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Virginia Cavalry Regiments, defeated a Union force and captured 150 men. The interior wooden elements and furnishings of the church suffered considerable damage during the war, but were replaced. The building was listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 1989 and it is an American Presbyterian Reformed Historical Site.

Ebenezer Methodist Church

Ebenezer Methodist Church, Stafford, VA was established in 1856. The original building was a brick structure built on donated land which is now at the corner of Onville Road and Ebenezer Church Road in Northern Stafford County. For 135 years, the church building remained at this location, surviving damage from the Civil War and ministering to generations of residents in the community. In 1991 the church was relocated on an eight acre parcel of land located next to Embrey Mill Road in Stafford.

Ebenezer United Methodist Church is said to have been an encampment for Federal troops on their journey from Manassas to Fredericksburg. According to the WPA Report, the interior of the church building was completely destroyed: the windows were broken, the pews were removed and the floor boards were torn up. The church appears today with an entirely remodeled interior with modern pews and new floors.

- Historic Resources Survey Stafford County Virginia – Stafford County Planning Department and Virginia Department of Historic Resources – Page 38 ↩︎

- “Colonial Churches in the Original Colony of Virginia”, Publ. 1908. By the Rev. John Moncure, D. D. ↩︎

- “Colonial Churches in the Original Colony of Virginia”, Publ. 1908. By the Rev. John Moncure, D. D. ↩︎

- An advertisement that appeared in the Virginia Gazette of June 6, 1751. ↩︎

- The contract to build Aquia Church was awarded to Mourning Richards of Drysdale Parish, King and Queen County, master builder and architect. The unfortunate accident befell the new church as it neared completion is recorded in the Virginia Gazette of March 21, 1755 ↩︎

- Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom ↩︎

- Historic Resources Survey Report of Stafford County June 1992 TRACERIES Page 39 ↩︎

- Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786) ↩︎

- The Disestablishment of the Church of Virginia – Aquia Episcopal Church Website ↩︎

- Holmes, David L. The Decline and Revival of the Church of Virginia Up from Independence: The Episcopal Church in Virginia, The Interdiocesan Bicentennial Committee of the Virginias, Orange, Virginia, 1976, p 57. ↩︎

- Historic Resources Survey Report of Stafford County June 1992 TRACERIES Page 39 ↩︎

- Historic Resources Survey Report of Stafford County June 1992 TRACERIES Page 33 ↩︎

- Historic Resources Survey Report of Stafford County June 1992 TRACERIES Page 34 ↩︎

- Historic Resources Survey Report of Stafford County June 1992 TRACERIES Page 34 ↩︎

- Mover, H. P. History of the Seventeenth regiment, Pa. volunteer cavalry or one hundred and sixty-second in line of Pa. volunteer regiments, war to suppress the rebellion, 1861-1865, Sowers Printing Company, Lebanon, PA, page 34. ↩︎

- Everett, Donald E. Chaplain Davis and Hood’s Texas Brigade, LSU Press, Apr 1, 1999, pg 47. ↩︎

- Everett, Donald E. Chaplain Davis and Hood’s Texas Brigade, LSU Press, Apr 1, 1999, pg 49.

↩︎ - Everett, Donald E. Chaplain Davis and Hood’s Texas Brigade, LSU Press, Apr 1, 1999, pg 54. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, Volume 1 Houghton, Mifflin, The Riverside Press, Cambridge, 1905, p 17. ↩︎

- National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet – Aquia Church Section 7 Page 3 ↩︎

I

LikeLike

I love your blog, David and Mary.

LikeLike