REVEREND PHILIP SLAUGHTER A SKETCH

By JANE CHAPMAN SLAUGHTER

Source: The William and Mary Quarterly , Jul., 1936, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Jul., 1936), pp. 435-456

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Philip Slaughter was born October 26, 1808, at Springfield, the home of his father, in Culpeper County, Virginia. His father was Captain Philip Slaughter of the 11th Continental regiment in the Army of the Revolution; his mother was a daughter of Colonel Thomas Towles, of Lancaster County, Virginia, and of Mary (Smith) Towles. As we cannot rightly understand the character of a man without knowing something of his heredity, I will speak somewhat concerning his parents. Elizabeth Towles Slaughter, his mother, was a woman firm, intelligent, affectionate, and of deep spirituality, whose strong personality and elevated character left a deep and lasting influence on the life and character of her off-spring. Her son Philip felt this and in his address called,-Christianity the key to the character and career of Washington, he makes this quotation,-“Behind every great man stands a great woman, his mother”; and I feel that just as Mary Ball left the impress of her forceful character upon that of her son George, so did Elizabeth Towles leave her impress indelibly upon her son, Philip; for from her, with his personal appearance, he seems to have inherited much of that brilliant talent which showed itself so conspicuously from early youth to his later years, years more fruitful, perhaps, than the old age of most men; years in which he rose upon the “eagle wings” of Christian oratory, leaving as its fruits the conversion of many souls. But of deeper import than his strength of oratory was that deep and fervent piety which shaped his life in the ministry of God. From his mother, too, he doubtless inherited his lifelong keen interest in the history of Virginia, just as he inherited the blood of his great uncle, Robert Beverley, the historian. Elizabeth Slaughter was a woman, who, although she had the care of many children, of countless guests, and of a large household of servants and dependents, was a lover of intellectual pursuits. It is told of her that as long as she lived, she habitually rose with the dawn to go to a large, quiet attic room in the old mansion, where, safe from interruption, she was accustomed to read, write and study for several hours each day, and where she not only gave religious instruction to her children and young relations, but prayed with them, and for them. It was to this attic room in old Springfield, and to his mother, I believe, that Philip Slaughter owed much of that creative inspiration, that warm enthusiasm for the holier, worthwhile things of life; things that made him a power for good, and a magnet toward the higher things of heaven.

Captain Philip Slaughter, born in 1758, had spent his early years of manhood in the hardships of a hard war, and had on him ever afterwards the burden of public duties, and of a large plantation, duties to which he minutely attended, as his diary attests. He was a man who seemed to have inherited with the public spirit and courage of his ancestors their scholarly tastes, as well as their many books. These books had been the mental food of his forefathers, the Colemans, Pendletons, Claytons and Slaughters, and thus nourished on their cultural traditions, Capt. Philip Slaughter believed in a classical education, and gave his children, and their many cousins who attended his private, home school[1] at Springfield, the best teachers to be had in those days, such *as Mr. Hoge, father of the Rev. Moses Hoge of Richmond, Mr. Robertson, the Fontains, the Maurys and that rare old nobleman, Louis Hue Girardin, whose patron, like Thomas Jefferson, he became at a later date; thus giving them, as far as possible the mental discipline and culture of Oxford and Edinburgh, Rouen and Paris. Rev. Philip Slaughter attended at fifteen years of age, an academy at Winchester, Virginia, kept by John Bruce, a very famous teacher of that day. We find in the diary of Captain Philip Slaughter, a diary which he had kept from the time of entering the army of the Revolution in 1776, to his death in 1849, this entry, “March 20th, 1823, Phil Slaughter went to Winchester Academy; Aron[2] going with him to carry his clothes.”

A Greek book is still extant bearing on the fly-leaf the name of the elder brother of Philip Slaughter, and his own name, and a statement, as follows: “Commenced this book March 15, 1823, under the tuition of John Bruce, principal of the Winchester Academy, together with G. A. Smith, W. H. Smith, M. Taylor, J. S. Turner, and T. Daily.” This book, Collectanea Graceca Majora, Vol. I, is interesting in its own right. It has copious notes in Greek, Latin and French, by Andreas Dalzel, A. M., member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Third American edition, published at Cambridge, Mass., 1819.

Captain Philip Slaughter was one of the commissioners appointed to select the site of the University of Virginia, and one among the first of its patrons, so to the University came his son Philip in March of 1825, he being at that time seventeen years of age; but with the same apparent ease with which he had mastered the contents of Graeca Majora, so he mastered his University course and graduated in law in 1828. He did not become a bookworm, nor devote all his time to study, for tradition tells of him that he “frolicked” a good bit and played cards more than he should have done, and, as Captain Philip relates to a brother-in-law in Kentucky, caused his parents much uneasiness, and it required several visits from his more staid elder brother to straighten him out and to pay his debts of honour, not to speak of a much more severe treatment later on, which effected a cure for all time.

The author well remembers hearing Dr. Charles Kent, while lecturing on Poe, relate a time honoured favorite joke of his, of how Poe, when he was once caught (it is supposed a little tipsy) rolling headlong down the steps of the rotunda, he, himself, be it understood, and not his “poet’s eyes, in fine frenzy, rolling” and on being sharply questioned by the irate professor-“Who is that disgraceful scamp rolling down there?” Until there came back the witty and pertinent answer from the inverted author of The Raven,, which he couched happily in the quickly thought of words of the bard of Hohenlinden,-” ‘Tis I, sir, rolling rapidly.” Dr. Kent added in defense of his hero, that after all, Poe was not more often found guilty of being “had up before the faculty” for such playful misdemeanors than several others he could name, who yet lived to bring honour on their Alma Mater,-Alden Bell for example, and Philip Slaughter, “The bright, particular star of the University, the banner pulpit orator of the South.” There happened at the recitals of this anecdote to be, each time, present a near relative of each of the two gentlemen he mentioned, and on their going up smiling to the lecturer’s desk to obtain further particulars, and telling of their relationship to the scapegraces, Dr. Kent laughed too, and added that, for the future, he must be wary of telling that anecdote or tapping that source again until time should have removed all danger of possible relatives present. Yet, whatever his professors may have thought of his escapades in those young, thoughtless days, Philip Slaughter was so far loved and honoured by his classmates as to be the one commissioned by them to invite a famous guest, Lafayette, then on his visit to Virginia, to a reception given in the rotunda. Moncure D. Conway tells us this fact, which he had learned from Philip Slaughter himself, and in speaking of him on this occasion adds,-“he told me with what emotion, he met that world famous man, whose name was a household word in his own home, since his father[3] and the Marquis had been warm friends and war comrades at Valley Forge. He told me also of his meeting with three ex-presidents, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, at Monticello, at a dinner given in honour of Lafayette.”

Thus, with the natural gaiety of youth, and the growing seriousness of manhood, Philip Slaughter passed his three years’ course of study at the University of Virginia and was admitted to the bar in 1828.

In a Memorial of the Rev. George Archibald Smith, who in December, 1826, took charge of St. Stephen’s Church, Culpeper, Philip Slaughter tells us of a strong life-long influence which came to him at this period thus,-“The present writer has a few pages of a journal in which is recorded the names of some persons who were the fruit of Mr. Smith’s ministry there, I, myself, having been presented to the Bishop for confirmation by him. I also remember that when I made my maiden speech, on a Fourth of July, at Washington’s Hotel at Stevensburg, Mr. Smith furnished me with books of reference, enabling me to give it a religious cast; and it is curious that when I made my last speech in Christ Church, Alexandria, at the Centennial of Washington’s inauguration, April 30, 1889, Mr. Smith,[4] at whose house I was sojourning, insisted upon reading the proofs, and supervising its passage through the press, this only a few weeks before his death.”

In regard to the final check-up that Philip Slaughter is said to have received in a rather wild career, his nephew, by marriage, the Rev. Thomas Forbes, of Accomac, gave me this incident of the old University life, as he had heard related in his youth: “I have often heard related the circumstance which changed the whole course of Uncle’s life and turned its current towards the ministry. It occurred while he was at the University. He and a chum of his were about to go to some entertainment, and had hired a sulky to take them, when they both got in and started off, the horse began to kick violently until the vehicle was overturned, and both young men thrown out. Philip Slaughter had his nose hurt which caused it to bleed profusely, the friend, not realizing how badly he himself was injured, endeavored to get up from the ground and go to the rescue of his comrade, but when he tried to rise he fell back, for one of his legs was terribly broken, a hurt from which he died in a few days.” The shock of his death and his grief for his friend inclined Philip Slaughter’s mind to such serious channels that his whole course of thought was diverted from the earthly law to the following of the higher Law of God, which was indeed, a fortunate turn for him, and gave great joy to both his parents. We find Captain Philip Slaughter mentioning this joy in a letter, in which he gives an account of the conversation which he had held with young Thomas Towles, a first cousin of his son, Philip, who it seems was going with a group of wild young men at Culpeper, and whom the Captain was, in a fatherly way, trying to divert from the error of his ways.[5]

One of Philip Slaughter’s biographers says of him, — “Dr. Slaughter began his career as a lawyer, but after a prosperous practice of five years, left the law for the pulpit.” It is presumed from his own words[6] that this practice was had at Culpeper. I herewith give quotations. “Mr. Green was my senior in age by several years, having been at the bar, while I was a student of the law at Culpeper, which place he persisted in calling Culpeper Courthouse, asking pardon, as he said, in a late letter to me, of the old burg, christened since the war Culpeper.”

Then again, on page 77, he says: “Richard Wigginton Thompson, late Secretary of the Navy, James French Strother, late member of Congress, Mr. Green and myself, who were all kinsmen and school-fellows made our first essays in the columns of a newspaper, in the Culpeper Gazette of that day. . . . Mr. Green and I had many tilts in the same newspaper, notably upon the division of the County of Culpeper, 1831, to which he was strongly opposed, and which I advocated. Wishing to do some sharpshooting from under cover, I got Stanton Field, brother of the judge, to be sponsor for that article. But the use of one word discovered me to my astute antagonist. The word was ‘exegesis,’ with which I, who had concluded to give up the law for the Gospel, had become familiar. Mr. Green, in his reply, said that there was but one person in the village whose studies made him familiar with theological terms. He then revenged himself upon me for my bushwhacking, by playfully reminding me of ‘a certain animal in the lion’s skin’ whose dialect betrayed him. This was a good hit, and I took it in good part, as it was intended to be taken.”

Philip Slaughter here showed that he was capable of that, –

“Stern joy which warriors feel “In foemen worthy of their steel”-

and he very amiably adds, on p. 78: “Mr. Green having been, as I said, my senior in age, and my superior in culture, generally got the advantage. If there were any exceptions to this rule, it would not become me to reproduce them.” And, again, he quotes Secretary Thompson as having recalled a quotation from Tom Moore that he had given in a Fourth of July speech at a barbecue in Sam Washington’s tavern in Stevensburg, adding that Mr. Slaughter applied the lines to “Jefferson, who had just made an unsuccessful application to dispose of his property by lottery to pay his debts.” In further confirmation of the view that Mr. Slaughter practiced law in Culpeper, his own words may be cited,-“I may say our paths of life parted at this point, Judge Green remaining at the bar, I going to the pulpit. During my term at the bar, I became the administrator of a large estate. A difficult question of law having arisen in my administration, I consulted Mr. Green, who gave me his written opinion.” In his chapter, in the Memoir of William Green, LL.D., on Hereditary Genius, p. 66, Philip Slaughter says that the “blood of the Claytons” is “fruitful of lawyers,” he then gives a list of the men of the law sprung, as he himself was, from the Claytons and Pendletons. It was from a Pendleton, Philip Pendleton, “the root of the family in Virginia,” that he, through his father, Captain Philip Slaughter, and his grandfather, Philip Clayton of Katalpa and of Essex County, derived his name Philip.

There is still extant a letter from Miss Agnes H. Marshall of Oak Hill, Fauquier County, Virginia, to her brother, John Marshall, a student at the University of Virginia. This letter is dated May 29, 1832. It gives us a little glimpse of Philip Slaughter, while “dividing the swift mind,” in regard to his vocation in life. The portion of the letter regarding Philip Slaughter is as follows:

Oak Hill, May 29th, 1832.

My dear brother,-

“I fear you think we have been very slow in writing to congratulate you on your having reached your twenty-first birthday. I assure you tho’ you did not hear from us on that day it did not pass unremembered by us. You are now your own master, and I hope you will be a blessing to your family and an ornament to society. Educated by such parents as we have been, great indeed would be our condemnation if we should be aught else.

We had a very interesting meeting in Alexandria. Sixty persons were added to the church and eight ministers ordained. Both Bishops were there and several ministers from the north. Among them Dr. Bedell of Philadelphia, who is the most impressive preacher I ever heard except Bishop Meade. The town was crowded to excess. Your friend Mr. Slaughter boarded in the house with us. He is a pleasing young man. He told me he should come and see us this summer. If vou call at his father’s8 on your return home remind him of his promise. He is about to become a student at the Theological Seminary. I am sorry for it. It is only because he has been so much pressed by Bishop Meade and other ministers to join the institution that he has consented to do so. He told Mary a day or two before he consented to join it that he would not do so. This business of pressing religious young men into the ministry I do not admire.”

If the young lady were right in her surmise, what she says shows the decided influence of Bishop William Meade on the life of Philip Slaughter, and for his good. The reverence he had for the good Bishop, the Memoir which he wrote of him shows.

In addition, we learn from Captain Slaughter’s diary that his son Philip went to the Episcopal Theological Seminary, at Alexandria, Virginia, in October, 1833, and also that he was ordained deacon by Bishop William Meade in Trinity Church, Staunton, Va., May 25, 1834, and also, in a letter dated September 14, 1832, which he wrote his wife’s brother, Dr. Thomas Towles, of Henderson, Kentucky, said,-“Philip, our youngest son, is studying Divinity and expects to be ordained in the Episcopal Church next winter.”

In her girlhood, Philip Slaughter’s mother, who so greatly influenced his life, had been, like all her family for generations past a member of the Episcopal Church, but had been disappointed in the conduct of the rather wild and gay young ministers sent out to us from England at that time, a period when we had no bishop of our own, but were supposed to be under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London.9

The proverb tells us that.-“When the cat’s away, the mice will play,” and the ministerial mice of grandmother’s day played to such purpose that the serious minded lady retired from the fold of the Episcopal Church to that of the Presbyterian Church, as more congenial to her spiritual tastes, and if, with all his genial sweetness, there was a touch of the austere Puritan in the religion of her son Philip and in that of his erstwhile monitor and elder brother, it was due, perhaps, to this influence, though, to the author’s mind, the religion of neither of these men was harmed by the inter-mixture.

Philip Slaughter was ordained priest in St. Paul’s Church, Alexandria, Virginia, July, 1835, by the Rt. Rev. Richard C. Moore. We are told by one of his biographers that his first parish was Dettingen Parish, Prince William County, Virginia. The author distinctly remembers hearing her uncle speak affectionately of Dettingen and of the interesting history of Dumfries, but Dr. Slaughter himself, says in a notice of his friend Bishop Joseph Pere Bell Wilmer, of Louisiana, who had been his classmate at the Theological Seminary of Virginia, that the first call of each was to St. Anne’s Parish, Albemarle County, Virginia, and that in after years they met in Albemarle County both as refugees.10

On June 24, 1834, while he was still but a deacon, Philip Slaughter was married to a beautiful and charming girl of only eighteen years of age, Anna Sophia Semmes, daughter of Dr. Thomas Semmes, of Alexandria, Virginia, who was much beloved by all who knew her. The author recalls an incident relative to this. When studying art at the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington she lived in Alexandria, and going to the shop of an old watchmaker, one day, she had a new main spring put in an ancestral watch which had the name of her brother, Robert Madison Slaughter, engraved inside the case. On asking the cost of the repair the old workman replied, “If it so happens you be any ways kin to her, who was Miss Anna Sophia Semmes, and is now Mrs. Parson Slaughter, it is nothing, for she was my Sunday school teacher when I was a little boy, she was the sweetest lady I ever knew, and I wouldn’t take a penny from anybody kin to her for anything in the world.” And he refused all compensation for the work itself of the repair. Regarding this marriage we find four entries in the diary of Captain Philip Slaughter: “June 7th, 1834, Daniel Slaughter to cash lent going to Phillip Slaughter’s wedding to Miss Ann Sophia Semmes of Alexandria, $20.00.” “June 15th, 1834, Philip Slaughter, our youngest son, went on today, to be married to Miss Semmes of Alexandria, on Tuesday, daughter of the late Dr. Thomas Semmes, of Alexandria.” “July 18th, 1834, received back from Alexandria, a letter directed to Phillip Slaughter, enclosing $20.00, he having left Alexandria.” “August 27th, 1834, Sent Philip Slaughter $20.00 enclosed in letter, by James Wylie Lee to Springs, also sent my carriage by Aron.”11

In 1836, when twenty-eight years of age, Philip Slaughter accepted a call to Christ Church, Georgetown, D. C., and it is presumed that taking charge of this church was the means of his knowing Mr. Corcoran12 and that the latter was one of his parishioners, since we have heard that Mr. Slaughter performed the ceremony of marriage for Mr. Corcoran, baptized his daughter, Louise, and was her Godfather. Mr. Corcoran became Mr. Slaughter’s close, devoted, lifelong friend and in his will bequeathed him a legacy.

In 1840 Philip Slaughter was at Upperville and Middleburg, having assumed charge of two parishes in Fauquier County, Virginia, and in 1843, he became rector of St. Paul’s Church, Petersburg, Virginia.

Regarding his success as a preacher, one of his biographers says, “He quickly became prominent as a remarkably effective preacher of the intensely evangelical type, and his services were in constant demand in series of meetings called ‘associations.’ In connection with these he preached in many of the city churches and rural parishes of Virginia.” “Though brief,” writes another biographer, “his active ministry was brilliant and effective. He had all the personal magnetism of Whitefield, the fire and spiritual power. Great crowds attended on his ministry and conversions were numbered by the hundreds.”13

Unfortunately his health began to fail, and feeling the need of rest and change, he spent the years of 1848-1849 in Europe, a trip which the means for taking he owed to his ever kind and generous friend, Mr. Wm. Corcoran. He has himself left an account of some portion of this trip in his ad- dress before the Historical Society of Virginia, delivered in the capitol at Richmond, in January, 1850, and which was afterwards printed by the society.14

In spite of this delightful European trip, his bad health continuing, he was compelled to give up the hope of further continuous pastoral work, and thus he returned to Richmond, where he published: The Virginia Colonizationist, a periodical devoted to the interests of the colonization of negro slaves in Africa, a class of people in whose welfare and conversion he had always taken the most heartfelt interest, an interest which remained with him through life, as any one must see who is familiar with his address called “The Colonial Church of Virginia,” delivered at Richmond, May 2, 1883. He discusses the Black Race (p. 22-27), and also mentions (on p. 24): “Another deeply interesting fact, which,” he says, “will surprise many of my hearers, is, that the first man who ever lifted up his voice against the African slave trade was one of the poor, despised Colonial clergymen of Virginia.” This clergyman, he tells us, was “the Rev. Morgan Godwyn,” who wrote, he adds, “a very strong pamphlet in Amerca,” entitled: The Negro’s & Indian’s Advocate, which was printed in London in 1680. The author recalls vividly, in this connection, that during prayers each morning in his household that his two negroes, a man servant, William, and a maid servant, Easter, had special seats, and they were usually present. Philip Slaughter edited The Virginia Colonizationist, we are told “with signal ability and was successful in enlisting the interest of the Virginia Legislature, and in securing large appropriations for the project.” This end being accomplished, he at this time returned to his own home, “The Highlands,” situated on the eastern slope of Slaughter’s Mountain, in Culpeper County. It was on his father’s estate, on the southeast skirt of this mountain, that with the aid of friends, but largely at his own expense, he erected a small church, called Calvary, and in this church he ministered to his relations, his friends, neighbors and servants.15 Many of these last were worthy, faithful descendants of the fine body of servants once owned by his father, and who had been reared on that very plantation. The author recalls some of them still serving her uncle, in her lifetime. This ministry in Calvary was entirely gratuitous and was continued until this church was destroyed by the National army in 1862. One of the most prized ornaments of Calvary was its stained glass window in the chancel, a window which has had an interesting history16, since it was thus rescued.

About 1870 another Episcopal Church was built a few miles away, near the railroad, in the little hamlet called Mitchells, and in its chancel was placed the rescued window with its dove of peace, its cross and crown. The first rector of this church was Rev. Charles Yancey Steptoe, whose first and only charge was Ridley Parish, cut off from St. Mark’s, in May, 1875, and here, in its churchyard, were interred the remains of Philip Slaughter, when he died on June 12, 1890. Later the family and friends of its old rector rebuilt Calvary at the foot of the Mountain and called it All Saint’s Chapel. When it was being built the Grand Army of the Republic was visiting the battlefield of Cedar Mountain and then occurred a rather pathetic incident; a soldier, evidently a very poor man, seeing them at work brought to Mrs. Thomas Slaughter, the Reverend Philip Slaughter’s daughter, a dime and said: “I was made, under orders from my officers, to help pull down that old church in 1862. I thought it was a sin then, and I think so still, and to prove it, here is this dime which I know will at least buy a shingle for the roof of the new church.” I have also heard it said that one of the officers who had commanded the destruction of old Calvary, gave quite a sum of money towards the building of the new All Saint’s Chapel, and now as in regard to the window, I will let good Mrs. Waller Yager17 speak again, as before in the note.

After the destruction in 1862 of his church, Calvary, Philip Slaughter edited at Petersburg a religious paper for soldiers and sailors, The Army and Navy Messenger, and also preached in camps and military hospitals. It was about this time, too, during the last eighteen months of the War Between the States that the Reverend Philip Slaughter, with his wife and two daughters, Mary, and Sophia Mercer, afterwards Mrs. Thomas Towles Slaughter, Jr., were in Albemarle. At first, after the entrance of Culpeper by the Union troops, making their home with Mr. William Nelson, their brother-in-law. Later, with Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter, his elder brother; both being forced to leave desolated homes and “refugee,” they occupied a house together. This house, since destroyed by fire, was near Scottsville on the old James River Canal. It was a big, old, ramshackle, rats’ castle of a dwelling, supposed to be haunted. Of the poor ghosts the author recalls nothing, for to her mind it was quite sufficiently haunted by huge, hungry rats, “Pied Piper of Hamlin” rats and by mice, “Bishop of Bingen” mice, badgered and starved by the said rats, that even nibbled the toes of the baby negroes in their cradles, and though grey-clad, were almost as great a terror to her as the Yankees, and like them all pervading, all devouring. In addition, every variety was in that house, of centipede, of cockroach, and almost every known tribe of ants-ants in several sizes and colors. Fierce big black warrior ants, many medium brown citizen ants, and millions of tiny red, proletarian ants, all, however, equally as good pioneering ad- venturers as Daniel Boone. These vermin, that the negroes termed “varmints,” should in all conscience, have sufficed, even for two families in one house, but, lo! a worse fate was yet in store for them, “the seat of war changed,” and there came over “the Ridge,” Sheridan, the ruthless, the despoiler of even the crows of the Valley of Virginia on his cruel way to join Grant at Petersburg. Sheridan, and his ten thousand made them a visit, or “raid,” as his little neighborly calls were termed-a very hasty visit it is true, for the Devil himself seemed to be on his heels, or he on the hoofs of the Devil, which the author never rightly knew; but it was all one, since as “birds of a feather flock together”; they caught up, joined forces and the little visit was quite long enough to scare a little girl nearly to death, and for him and his men to do all the harm to us Les Miserables, or as the old soldier said, Lee’s Miserables, and I was one of ’em, that they could. His troopers were literally like those of Xenophon, in the ten thousand, but, alas! not retreating they arrived about sunset, coming staving down the long driveway from the woods to the house,-as if-

“All the fiends from Heaven that fell”-

were on their trail, little military caps, like saucepans pulled down over their hard faces, grim set, bouncing up and down on their hard trotting cavalry horses, cursing, spreading everywhere, swarming over everything like the roaches, devouring like the rats. The one only thing that saved old Stony Point house was that Philip Slaughter, a minister of the Gospel, on the rumor of their approach, for they had been some days in the vicinity, had petitioned someone in power for a guard, and obtained three Union soldiers, one to guard the front and two for the back premises, which, unfortunately, did not include the out kitchen, cabins, or smoke house, or the stables. As for the barn, there was left us from former raids but one forlorn, old red cow, named Jinnie, but Jinnie had been with us since “before de war,” she was an old stager and, I suppose, looked too tough to tempt, even the appetite of a Yankee trooper, for she was left alone, but, as ill-luck would have it, the great, boat-shaped green farm wagon had just returned from Forest View, the plantation in Madison, and had brought back the “crop” of forty turkeys, that Uncle Joshua, the gardener, Aunt Cely his wife, and the overseer, George Washington Hawley, who were the sole caretakers, had raised. These turkeys, fine Confederate grey birds, had been expected to furnish food for the two families and servants for some time to come, for the bacon had long since been taken, and Uncle Gared, the wagon driver had in all haste shut them into the smokehouse, the other fowls in the anticipation of foul play, had been “refugeed” to the upper storeroom in the “big house,” where they were safe under the protection of the Union guard. But not so the turkeys, doubt- less feeling that they were, as the Yankees said, “damned rebels,” or more politely, “condemned to death,” were vigorously, and unanimously lifting their poor “Johnie-Reb” voices against fate and their unnatural imprisonment. Just as they anticipated, their stronghold was forced and they were ruthlessly and quickly decapitated with sabres, and, as their executioners were in a hurry, they were piled up at the wood- pile and burnt to the last feather. This was not the only vandalism that the children saw from the upper windows. The old family cook, Aunt Sally Banks, was made to serve the officers with dinner on the rear lawn, and as each man finished his meal from the very best blue, ancestral, imported- from-England-China, and by way of returning thanks, he took his plate and staved it against the trunk of one of the big oak trees, reducing it to fragments. The night was falling and the self-invited guests camped all over the lawn and nearby meadow and remained with us all night, an awesome, frightened night it was, too, for the inhabitants of the house, who could see through the darkness a circle of neighboring houses in flames. Some of the neighbors, dwellers in these houses took refuge with the two families in the Moon house, notably one old lady who seemed to be, from the rotundity of her figure, a relative of Falstaff, stout in figure, though not in heart, for she came to us in tears, but when she went to bed it was discovered to the no small astonishment and merriment of the children that she was wearing, by way of a “bustle,” her grandmother’s big silver punch bowl and that she was literally wreathed around with a string of the daguerreo- types of her relatives. Poor lady! She lost her pair of carriage horses and her colored servant boy, taken by the marauders when they left early next morning, as did Philip Slaughter lose his carriage horses and negro man, and Dr. Slaughter, his brother, lost all remaining of his horses, save Ball, a feeble old equine that could not make the trip to Hades, or wherever they were bound. But, far worse than the loss of the horses, was the loss of a wounded Confederate officer, a relative, who was forced to go with them, riding his beautiful battle charger, Nellie Grey. Ill, though he was, and hardly able to sit erect in the saddle, he had to go with the ten thousand demons. However, here again the minister of the Gospel, who had a strong ally in the husband of his niece, who had married General Ord, U. S. A., was able to prevail against the vandals, for Grant, a West Pointer, had a soldier’s chivalry, as he afterwards showed in his treatment of General Lee, and the wounded officer was allowed to return, but not so the good horse. Oh, no! The memory of the appearance of the highroad leading from Stony Point to Scottsville remains with the author to this day, the ground was soft and muddy and the rapid galloping of the ten thousand cavalry horses had left their footprints knee-deep in the mire, until it resembled nothing so much as a gigantic honeycomb.

After the surrender in April, 1865, Philip Slaughter, was for some time, in Richmond, where he was associate editor of the Southern Churchman.

Concerning Dr. Slaughter in the pulpit and in the editorial chair, the author would like to quote his own words, which he used in connection with the work of the Rev. George A. Smith, “The preaching of the Gosepl with the living voice to the listening numbers, when that voice is the echo of thoughts and emotions which are beating at one’s heart and leaping to one’s lips for utterance, is a mighty power for convincing the judgment, awakening the conscience, moving the hearts and moulding the manners of men. But when from want of voice, one is obliged to come down from the pulpit, it is a great privilege to sit in the editor’s chair. He at once becomes ‘Sir Oracle,’ and his pen, if it be guided by a vigorous and well-furnished brain, may exert an influence wider than the priestess of Apollo dispensing oracles from the tripod of Delphi. They who thus catch the public attention and keep it by iteration and reiteration, from week to week, always having the last word, should be the masters of public opinion.”

From this quotation we can have no doubt that his ruling passion for doing good was satisfied as was that of the Rev. Geo. A. Smith, as editor of the Episcopal Recorder. He then returned to his old home, The Highlands. In a conversation with a guest, Moncure D. Conway, he afterwards described the condition in which he found his possessions, pillaged, scattered, mutilated, burnt.18

As his beloved church, Calvary, was now destroyed, it was at this time that he had built, as an annex to the west side of his large parlor, the small recess chancel which I have before spoken of, as containing the “refugeed” window with its dove and olive branch, and in this chancel the faithful pastor renewed his preaching of God’s Word. The window remained in the private chapel until the building of the new Calvary at Mitchells, when the window was placed there, and there rested until he second Calvary, which was hastily and badly built, was struck by lightning and became ruin- ous. In the meantime Emmanuel Church, in what is now Slaughter Parish was built and dedicated December 13, 1873. It is situated on the Rapidan River in the small village of the same name. Philip Slaughter was called to take charge of Emmanuel, accepted the call and served there as long as his health and strength permitted, for about two years. His daughter, Mrs. Thomas Towles Slaughter, Jr., and his niece, Miss Bessie Slaughter, with Mrs. Agnes Maupin, Mrs. Fielding Lewis Willis and other volunteers, furnishing the music.

In 1874 Rev. Philip Slaughter received the degree of D. D. from the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

In 1879 he was elected historiographer of the Diocese of Virginia, which office he filled until his death. The Parish in which he served during his last years was called for him, Slaughter Parish.

Dr. Slaughter died June 12, 1890 and he was, with heartfelt sorrow by his family and many friends, laid to rest in the churchyard of the second Calvary at Mitchells, Culpeper County. But when All Saint’s Chapel, on the site of the first Calvary Church, at the foot of the mountain, was built, his remains were removed and placed in the church yard there, where were the graves of several of his former parishioners, who had looked to him for spiritual guidance in the olden days, and who had loved him as pastor and friend. Thus the faithful minister of God and good shepherd of his flock, now lies there, on his ancestral ground, in the protecting shadow of that old, beloved mountain, far’above on the side of which he had thought and worked and prayed for the “whole state of Christ Church militant,” and had so often seen the dim, grey dawn break through the veiling branches of his favorite trees, had loved to watch the sun rise in rosy clouds out of a sea of silver mist stretching away to the east- ward, a dewy mist, which he often said recalled to him the infinite line of old ocean, lying rimmed across the far horizon.

Dr. Brock, who knew him well, speaks thus,-“Few men have been more inspiring in stimulating their fellows in this state, with regard for its past history, and in quickening into active fruition their inherent veneration and pious sensibilities, than the subject of this sketch. Richly endowed, as he was, with the persuasive charms of the orator, and so possessed with that insatiate zeal to know, to guide, and to in- struct, which neither the infirmities of age could quench, nor physical anguish scarce restrict, he wrought to the very end, with such potency and excellence, that in pulpit or page, there was perceptible in his latest utterances no diminution in quality. Beloved sage!-he was taken to the Father in full mental panoply, and with plans of peculiar usefulness and beneficence still in progress.”

It has also been said of him by one who knew him well,- “In his case, life was so full and vigorous to the day that he was taken ill that it seems more like the cutting off a man in his prime, than the fading out of one weary with the toils of life.”

“As in other noble instances in which the predominant animus has been the good of others, subordinating thought of self, the life of Dr. Slaughter was touching in its exemplifications of simplicity, self-denial and generosity. In his home he was most tender and considerate as husband and father.” The author has tried to show how this tender consideration traversed the eight miles of distance between them to her home and what a ray of sunshine it brought into her life and how it watched over her path as child and young girl, until the sun of the noble heart from which it emanated was set in this world, to rise in a brighter sphere, yet leaving to her still, its afterglow of happy memories, as inspiration.

To quote the words of Dr. Brock again: “The desolation of war with him, involved not only res angusta domi, but for a time inadequate domestic service, during which, many du- ties to which he was wholly unaccustomed were cheerfully undertaken by him.”

Rev. Joseph Packard of the Theological Seminary of Virginia, thus aptly presents the personal characteristics of Dr. Slaughter: “No one who knew him can forget the warmth of his friendship, the charm of his conversation, his literary taste, shown in his familiarity with the best English literature and poetry, laid up in a remarkably retentive memory and above all, to use his own language in writing of Rev. Dr. May, ‘in the constant shining of the light and the savour of the salt that was in him, in the brotherly kindness which beamed from his eye, flowed from his lips, and emanated from his whole demeanor’.”

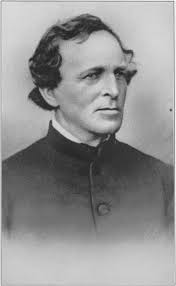

In his physical appearance Dr. Slaughter resembled his mother’s people, being very tall, and as straight as an arrow, with broad shoulders and an imposing presence of great dignity. Dr. Stanard says of him,-“strikingly handsome, even in his old age.” This tall figure was surmounted by a well-shaped head with a broad dome-like forehead with straight black eye- brows, from under which flashed with enthusiasm, or gleamed with mischief-for their owner was full to the brim of kindly fun-a pair of bright, keen, searching, dark blue eyes, eyes that could flash like a steel blade. Anyone who had ever met that eagle glance rarely would forget it. Yet, for all that, they were kind eyes, full of understanding, sympathy and compassion for suffering in any form, the eyes of one, brave, yet tender,-“Whose pity gave, ere charity began.” Dr. Slaughter’s keen sense of humor, the “best possession, next to the grace of God,” gave a delightful flavor to his conversation; children and the young around him were fascinated by him and all unconsciously drawn towards him. Judge Daniel Grinnan, then President of the Historical Society of Virginia, recalls his visiting Brampton, the home of the Judge’s father, Dr. A. G. Grinnan, and relates that he talked a great deal, but delightfully, in reminiscence of the days and people whom he had known in his youth. He adds an anecdote of the European tour which, for want of space, I must reserve for a future occasion.

After Philip Slaughter’s health failed too much for him to pursue the active work of the ministry, he devoted himself largely to historical and genealogical studies, subjects in which he had always been deeply interested, and in which studies he grew more and more enthusiastic as time went on. In 1846 he had published A History of Bristol Parish, and in 1847 A History of St. George’s, both of which were revised and republished, Bristol Parish in 1879, by himself, and St. George’s Parish19 in 1890 by Dr. R. A. Brock. “The publication of these,” says Dr. G. McLaren Brydon, “did much to arouse interest in the preservation of the original records of many parishes and in the protection of the historical records of the State.” Mr. Slaughter had formulated a plan for the preparation of a general history of the old parishes and families of Virginia, and for years had been gathering material, but his declining health compelled him to relinquish the task and to turn the material over to Bishop William Meade, who, after years of research, published in 1857 his monumental work, “Old Churches, Ministers and Families of Virginia.”

Philip Slaughter wrote A History of St. Mark’s Parish, 1877. The author recalls the enthusiastic joy and pleasure that he took in this work, and in his various “finds.” He would frequently ride over to Madison to share his discoveries with his brother, Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter, an ever sympathetic auditor; he found another even more sympathetic in Dr. A. G. Grinnan of Brampton, nearby, who himself, had a great love of the research work of an antiquarian. At the time of Dr. Slaughter’s death in 1890, he had practically finished The History of Truro Parish, which was published in 1908 by the Rev. Edward L. Goodwin.

Philip Slaughter was the author of many historical pamphlets and addresses, such as: The Virginian History of African Colonization, 1855; A Sketch of the Life of Randolph Fairfax, 1864; Memoir of Colonel Joshua Fry, 1880; Christianity the Key to the Character and Career of Washington, 1886. His more significant monographs include his address at the semi-centennial of the Theological Seminary in Virginia, 1873; a paper on historic churches of Virginia, printed in W. S. Perry’s papers relating to the history of the church in Virginia; The History of the American Episcopal Church, 1885; The Colonial Church in Virginia, published in Addresses and Historical Papers Before the Centennial Council of the Protestant Episcopal Church in Virginia, 1885; and a biography of the Rt. Rev. William Meade, in Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Vol. IV, 1885.

Moncure D. Conway, in his Barons of the Potomack and Rappahannock, tells of a visit to Rev. Philip Slaughter at the High- lands, 1889, as follows: “The first to discover the error of the biographers in stating that the Washingtons moved from Wake- field to the farm near Fredericksburg was Rev. Dr. Philip Slaughter, historiographer of the Diocese of Virginia, though the true facts do not appear in any of his works, being found after his days as an author were past. Alas! how do I mourn that I cannot compensate that venerable friend for the in- formation entrusted to me by hastening to gladden his heart with the revelations of these newly discovered letters! I can- not forbear introducing here some brief tribute to our old master in Virginia lore, by whose death, June 12, 1890, all historical students are bereaved indeed. Dr. Slaughter, born October 26, 1808, in Culpeper County, was not only the author of the historical and biographical monographs bearing his name, but contributed something to most of the work of that kind done in Virginia during his time, including the important volumes of his friend, Bishop Meade.”

“A thorough and exact investigator, caring little for his own fame as a discoverer, but much for the truth of history, he was consulted by historical writers long before his appointment, 1879, as historiographer, and freely distributed his stores of information asking neither credit or return. . . Dr. Slaughter began his career as a lawyer, but after five years of prosperous practice left the bar for the pulpit. His sympathies were deeply stirred for the slave, and he was one of the first to throw himself into the cause of African colonization. In 1850 he founded and edited in Richmond the Virginia Colonizationist. In 1856 he established himself in Culpeper County, at Cedar Mountain, where he built a church at his own expense, and preached without remuneration, ministering with especial care to the negroes. His church was destroyed in the terrible battle of Cedar Mountain, and his invaluable library, containing precious manuscripts accumulated through many years, pillaged, torn, scattered by the contending armies. When he returned to his home, he found bits of his treasured papers strewn about the grounds. He told me that a friend, visiting Philadelphia, remarked on a centre table there, one of his valuable books, containing his book-mark. He never applied for it, and in narrating these things the great-hearted clergyman uttered no murmur. When I visited him at Cedar Mountain in the year before his death, he appeared to me a sort of avatar of the old Virginian race, whose annals he had so largely recovered and preserved. His ancestors and those of his wife (nee Semmes, of Alexandria) had lived in the same region for two hundred and fifty years before them. They had inherited traditions so vivid that the scholar talked of the Spotswoods, Washingtons, and other worthies, as if they were old friends. His mind was clear, his memory exact, his heart full of sun- shine, as if he were still in life’s morning, instead of his eightieth year. With his wife and children around him in his pretty home, commanding a beautiful landscape, honored by his State, beloved by all who knew him, with a life of long and faithful services to humanity and to literature to look back on, the historiographer remains in my memory as an almost ideal figure. Although he had suffered many losses, he had nothing to grieve for, except that he was unable to publish to the world the results of his later investigations; and these he carefully made known to me, in words and by letters. As I was last parting from him, he said, ‘Since the recent discovery of the ancient Truro Parish Vestry-Book and Manuscript, containing so much of interest concerning the Washingtons and others, I have longed for a new lease of strength to edit and publish it. Can you not find in the North some wealthy gentleman who will provide means for publishing this most important document? A page containing autographs of the vestrymen, Washington, George Mason and others has been carried off and is now in the New York Historical Society, and some few parts are missing or dam- aged, but the substantial historical value of the manuscript is not impaired. I must leave these things to younger men. I feel a great satisfaction in delivering to all the information I possess. It is a relief to know that if it be of any worth it will not die with me’.”

[1] Which he called Locust Dale. The Locust Dale in Madison County was called after it by its founder, Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter, his son.

[2] “Aron” is often mentioned in the diary. At Springfield, tradition tells, there were six Aarons, Miller Aaron, Shoemaker Aaron, Carpenter Aaron, Old Aaron, Little Aaron and Snowball Aaron, so called by his fellow servants because he was so black.

[3] “John Marshall, Major Gabriel Long, and Capt. Philip Slaughter were invited by the State of Virginia to accompany Gen. Lafayette through the State, the State paying their expenses.” Reminiscences of Distinguished Men, by Wm. B. Slaughter, p. 113.

[4] Mr. Smith had married, February 14, 1825, Ophelia Ann, daughter of Isaac Hite Williams and his wife Lucy Coleman, daughter of Philip Slaughter, officer of the Revolution, and his wife, wife, Margaret French Strother.

[5] It has often been brought up that Philip Slaughter led rather a wild life as a student at the University of Virginia. In regard to this the author quotes his words of dedication of his first book, to the- “Professors, Alumni and Students of the University of Virginia, This humble contribution to the solution of an interesting problem is inscribed as a small token of respect for my Alma Mater. I look back upon the years of my boyhood spent within the walls of the University with feelings of pleasure and regret,-of pleasure in the memory of privi- leges enjoyed and friendships formed, of regret for privileges abused and friendships broken by death. That the present students and those who shall succeed them may so pass their time that they can look back upon it with pleasure and no regret, and that each of them may be an honor to the University, to his country, to his God, and to himself, is the sincere prayer of-The Author. May 10, 1860.”

[6] Memoir of William Green, pp. 73-76.

8 Springfield, Culpeper County, Virginia

9 Dr. Slaughter tells us in regard to the young clergy, that,-“It was impossible to supply our pulpit with a native ministry; and the people who would not be without the offices of the Church, were forced to tolerate many ministers who left their country for their country’s good.” He quotes the words of Hammond, a chronicler of the time: “Many came who wore black coats, could babble in the pulpit and roar in the tavern.” In regard to the Bishop of London he tells us that,-“As an historical fact the Bishop of London had no legal jurisdiction in the colonies” (The Colonial Church in Virginia, p. 30), and again,-“to say that we had a bishop in London, is, little to the purpose, if not a mockery. The Bishop of London never made a single visitation to Virginia in a hundred and seventy-five years.” (Idem, p. 29.)

10 A Sermon on All Saints’ Day, p. 14

11 The author, a poor accountant, wants the riddle solved. Who bor- rowed the $20.00, originally? In regard to the spelling of the names “Phillip” and “Aron,” Captain Philip, though usually a correct and careful speller, showed that when occasion offered, that like Thomas Jefferson, he believed in the Declaration of Independence and practised his belief.

12 Mr. Corcoran’s full name was William Wilson Corcoran; his father came to America from Ireland, and the son was born in Baltimore, became a banker of some wealth and among other things founded Corcoran Gallery and School of Art, Washington, D. C.

13 The author recalls that, for emphasis, Philip Slaughter habitually lowered his sonorous voice to a deep, quiet tone, and you might have “heard a pin drop,” the audience was so attentive.

14 Rev. Philip Slaughter was a member of the Historical Society of Virginia, as well as of the Historical Society of Wisconsin, and of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston, Mass.

15 The word “slave” was never used in the Slaughter family, always “our people,” or “servants.”

16 Mrs. Nina Yager, one of Dr. Slaughter’s parishioners, tells the story:-“It was my husband’s two sisters, Bettie and Sophia Yager who saved the window. They were standing in their yard, when the church was destroyed, and saw the Yankees crossing their field with the window and they remarked the one to the other, ‘Let’s try to get that window back for Parson Slaughter,’ as they called him, and so they ran across the field and asked the soldiers to give them the window. One Yankee said, after some parley: ‘If it is a Catholic Church, we will.’ One of the girls im- mediately replied: ‘Don’t you see the cross?’ [Part of the design of the window is a cross and crown.] Then he gave it to them. It was very heavy, indeed, and the girls thought that they would never reach the house with it, but after a long time, they did, they put it up in the attic under a feather bed, till the war was over, when they gave it back to Rev. Philip Slaughter.”

17 “Mr. Slaughter performed the marriage ceremony for my parents [Major Smoot and Miss Crittenden], and twenty-three years later for myself and Mr. Yager, and afterwards when my son Edward was seven years old, he asked to be baptized in the home of the Reverend Philip Slaughter, under the window we have mentioned; as you know, Edward is the nephew of the two Yager girls who saved the window. I may supplement this touching story by adding, of course the request of the faithful, affectionate child was granted. Edward was duly baptized ‘a soldier and servant of Christ,’ by the Reverend George Mosely Murray, on the spot that he had chosen, and on the 12th of June, the anniversary of the death of his old friend and loving pastor. I must also add that about 1866, when the two loyal girls gave back the window to their ‘Parson,’ as there was then no place to put it, the ‘Parson’ had a chancel built for his temporary use on the north side of his own big parlour and in it he placed the win- down, communion table and reading desk which had also been saved from other churches of his charge, and there under the window, in this chapel he ministered to such of his old congregation as gathered to hear his beloved voice.”

18 Barons of the Potomack and Rappahannock, p. 60.