John Washington was born into slavery on May 20, 1838, in Fredericksburg, Virginia. His mother was Sarah Tucker, an enslaved woman, and his father was a white man. His mother, Sarah, was rebellious and tried to escape several times during his childhood. The first time, she was punished by being hired out for a time as a field hand. Despite the hardships, she took the time to teach him to read and write. After the end of the war, Washington penned one of the few escaped slave narratives, Memorys [sic] of the Past, in 1873. The narrative below from Washington’s Memorys, his passage across the Rappahannock to freedom in April 1862, encapsulates the high point of his life, a slave no more. Washington crossed just hours after the arrival of the Union army at Falmouth; indeed, he may have been the first to do so, the first of more than 10,000 – 12,00 more to follow.

First Night of Freedom – John Washington’s “A Slave’s Narrative.”1

April 18th 1862, Was “Good-Friday,” the Day was a mild pleasant one with the Sun shining brightly and every thing unusally quite [sic]. the Hotel was crowded with boarders who was Seated at breakfast a rumor had been circulated amoung them that the Yankees Was advancing, but nobody Seemed to beleive it, until Every body Was Startled by Several reports of cannon.

Then in an instant all Was Wild confusion as a calvary Man dashed into the Dining Room and Said “The Yankees is in Falmouth.” Every body was on their feet at once, No-body finished but Some ran to their rooms to get a few things, Officers and Soilders hurried to their Quarters Every Where Was hurried Words and hasty foot Steps.

Mr Mazene Who had hurried to his room now came running back called me out in the Hall and thrust a roll of Bank notes in my hand and hurriedly told me to pay off all the Servants, and Shut up the house and take charge of every thing. “If the Yankees catch Me they will kill me So I can’t Stay here,[”] “Said he” and was off at full speed like the Wind. In less time than it takes me to Write these lines, every White Man was out the house. Every Man Servant was out on the house top looking over the River at the Yankees for their glistening bayonets could easiely be Seen I could not begin to Express My New born hopes for I felt already like I was certain of my freedom now.

By this time the Two Bridges crossing the River here was on fire the Match having been applied by the retreating rebels. 18 vessels and 2 steamers at the Wharf was also burning.

In 2 hours from the firing of the First gun, Every Store in town was closed. Every White Man had run away or hid himself Every White Woman had Shut themselves in doors. No one could be seen on the Streets but the Colord people. and every one of them Seemed to be in the best of humor. Every rebel Soilder had left the town and only a few of them hid in the Woods West of the town Watching. The Yankees turned out to be the 1st Brigade of “Kings Division,”* of McDowells Corpse [sic], under Brigader Genl Auger, having advanced as far as Falmouth they had stoped on Ficklins Hill over looking the little town. Genl Auger discovered a rebel Artillery on the oppisite Side of the river, Who after Setting fire to the Bridge was fireing at the Piers trying to knock them down the “Yankees” Soon turned Several Peices loose on the rebels who after a few Shots beat a hasty retreat; coming through Fredericksburg a a [sic] break neck speed as if the “Yankees” was at their heels.

As Soon as I had Seen all things put to rights at the hotel, and the Doors closed and Shutters put up, I call all the Servants in the Bar-Room and treated them all around plentifull. and after drinking “the Yankees,” healths,” I paid each one according to Orders. I told them they could go just Where they pleased but be Sure the “Yankees,” have no trubble finding them.

I then put the keys into my pocketts and proceeded to the Bank Where my old Mistress lived Who was hurridly packing her Silver-Spoons to go out in the Country, to get away from the “Yankees.” She asked Me with tears in her Eyes What was I going to do. I replyed I am going back to the Hotel now after you get through “Said She,” child you better come and go out in the country with me, So as to keep away from the Yankees, Yes Madam “I replyed” I will come right back directly. I proceedeed down to Where Mrs Mazene lives (the Propietiors Wife) and deliverd the keys to her.

SAFE IN THE LINES

After delivering the hotel keys to Mrs Mazene I then Walked up Water St above Coalters Bridge Where I noticed a large crowd of the people Standing Eagerly gazeing across the River at a Small group of officers and Soilders who was now approaching the river Side and Immediately raised a flag of Truce and called out for Some one to come over to them. A White Man named James Turner, Stepped into a Small boat and went over to them. and after a few Minutes returned with Capt. Wood of Harris’ Light Calvary, of New York. Who as Soon as he had Landed proceeded up the hill to the crowd amoung which Was the Mayor, “Common Council,” and the Corporation Attorney, Thomas Barton.

Capt Wood then in the name of Genl Auger, commanding the U.S. Troops on the Falmouth Heights demanded the unconditional Surrender of its Town. Old Lawer [Lawyer] Barton was bitterly opposed to Surrendering, Saying “the Confederacy had a plenty of Troops yet at their command.” Then Why did they burn all the Bridges When We appeared on “Ficklins Heights?” demanded Capt Wood—Barton was Silent. “The Orders are “continued Capt Wood” that if any further attempt is made to burn Cotton or any thing else, or if any Trains of Cars Shall approach or attempt to leave the town Without permission of Genl Auger the Town Will be immediately fired upon.

The Mayor and “Common Council” hesitated no longer. Notwithstanding Lawer Barton’s objection, and Capt Wood then Informed the Mayor that he would be required to come over to Genl Augers Headquarters the Next Morning at 10. 0.clock, and Sign the proper papers. He then bid them all good evening and having again entered the little Boat he Was Soon rowed across the River and in a few Minutes there after he was Seen mounted on horse back and being joined by Scores of other Horsemen, that had not been Seen While he was on our Side of the river. Evidently having been concealed in the Woods near by.

As Soon as the Officer had left the Constables was told to order the Negroes home Which they did, but While we dispersed from thereabout, a great many did not go home just then. I hastened off in the direction of home and after making a circutous route, I ‘m in company with James Washington, my first Cusin and another free Colord Man, left the town near the Woolen Mills and proceeded up the road leading to Falmouth[,] Our object being to get right opposite the “Union Camp,” and listen to the great number of “Bands” then playing those marching tunes, “the Star Spangled Banner,” “Red White and Blue,” etc.

We left the road just before we got to “Ficklin’s Mill,” and walked down to the river. The long line of Sentinels on the other Side doing duty colose to the Waters Edge.

Very Soon, one of a party of Soilders, in a boat call out to the crowd Standing arround Me do any of you want to come over—Every body “Said No.” I hallowed out, “Yes I Want to come over.” “All right—Bully for you,” was the response. and they was Soon over to Our Side. I greeted them gladly and Stepped into their Boat. As Soon as James, Saw my determernation to go, he joines Me, and the other Young Man who had come along with us—

After we had landed on the other Side, a large crowd of the Soilders off duty, gathered around us and asked all kinds of questions in reference to the Whereabouts of the “Rebels” I had stuffed My pockets full of Rebel Newspapers and, I distributed them around as far as they would go greatly to the delight of the Men, and by this act Won their good opinions right away. I told them I was most happy to See them all that I had been looking for them for a long time. Just here” one of them asked me I Geuss you ain’t a Secessish,” then. Me “Said I,” Why know [sic] Colord people ain’t Secessh” why you ain’t a Colord Man are you “Said he.” Yes Sir I am “I replyed.” and a Slave all my life. All of them Seemed to [be] utterly astonished. “So you Want to be free inquired one.” by all Means “I answered.” “Where is your Master? Said another. In the Rebel Navy, “I said.” well you don’t belong to any body then, “Said Several at once” the District of Columbia is free now. Emancapated 2 Days ago. I did not know what to Say, for I was dumb With Joy and could only thank God and Laugh. They insisted upon My going up to their camp on the Hill, and continued to ask all kinds of questions about the “rebs.” I was conducted all over their camp and Shown Every thing that could interest me

Most kind attention Was Shown me by a Corporal in Company H, 21st New York State Volenteers. He Shared his meals and his bed with me and Seemed to pity me with all his Manly heart, his name was “Charles Ladd,” But our aquaintance was of Short duration a few Weeks thereafter the army advanced and had Several Skirmishes and I never Seen him again.

It was near night before I thought of returning home (for though there was not as yet any of the “Union Troops” in Fredericksburg) the Town was right under their Guns and a close Watch was being kept on the Town.

When My friends (the Soilders) and Me arrived at the River Side We found the Boat drawn out of the Water and all Intercorse forbiden for the Night. My cousin and his friends had recrossed early in the afternoon.

So I found I Should have to remain with my new found friends for the Night. However I was well aquainted in Falmouth and Soon found the Soft Side of a Wooden Bench; at Mrs Butlers who had given up an outside room for the use of Some Soilders and 3 or 4 of us. A good fire was kept burning at night in an old fashiond fire-place.

A Most Memorable night that was to me the Soilders assured me that I was now a free man and had Nothing to do but to Stay With. They told me I could Soon get a Situation Waiting on Some of the officers. I had already been offered one or two, and had determined to take one or the other, as Soon as I could go over and get my cloths and Some $30.00 of my own.

Before Morning I had began to fee[l] like I had truly Escaped from the hands of the Slaves Master and With the help of God, I never Would be a Slave no more. I felt for the first time in my life that I could now claim Every cent that I should Work for as My own. I began now to feel that Life had a new joy awaiting me. I Might now go and come when I please So I wood remain With the army until I got Enough Money to travel further North This was the FIRST NIGHT of my FREEDOM. It was good Friday indeed the Best Friday I had ever Seen. Thank God—

The Pathway to John Washington’s First Night of Freedom.

Occupation of Falmouth, Virginia

It is important to understand the role that the Union Army occupation of Falmouth played in the Underground Railroad, and we will go into more detail on that below. Even with the bridges down between Fredericksburg and Falmouth the crossing of the Rappahannock was easily done. Once on the Falmouth side of the river the Union Army, through Falmouth Station, readily transported the freedom seekers to Aquia Landing by railroad and then to Washington DC by Steam Ship.

Aquia Landing was a terminus of the R F & P RR (Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad) and figured prominently in a route taken by enslaved African Americans as freedom seekers traveling to points further north. These freedom seekers used this route prior to and during the Civil War. From Aquia Landing and steam ship up the Potomac to Washington, they endeavored to escape bondage.

Aquia Landing, The Underground Railroad & Henry Box Brown

When we visited the Conway House, there was a park directly across the street from it. It was just a short walk to the edge of the Rappahannock River. Wading across the river would not have been difficult. With the Confederate army removing themselves from this area, and with the Union Army providing the assurance that freedom was on the other shore of Fredericksburg, thousands of Freedom Seekers flooded Falmouth. Pictured below are both pictures of African slaves crossing during the time of the occupation of Falmouth and pictures we took showing how it looks today. It was obvious, and we can still see this today, that crossing the Rappahannock was not that difficult considering the Confederates had left the Fredericksburg crossing area and the Union soldiers were more than helpful in facilitating the crossing.

Word spread throughout the slave population in central Virginia that deliverance lay across the river. Thousands made their way across by foot, by cart, by skiff, or boat. Once on the other side they often found sustenance serving with the Union army.

Once on the Falmouth side of the river John Washington wrote of that moment in his life, “A Most Memorable night that was to me the Soilders assured me that I was now a free man and had Nothing to do but to Stay With. They told me I could Soon get a Situation Waiting on Some of the officers. I had already been offered one or two, and had determined to take one or the other.” John would serve the Union army as a servant for Major General Rufus King for a period between April and August. He eventually escaped to Washington, D.C., and was eventually joined there by his wife and newborn son, his mother, and her husband. Washington worked as a painter after the war and was active in the Baptist church. He wrote his narrative in 1873 and died at the Massachusetts home of one of his sons in 1918.

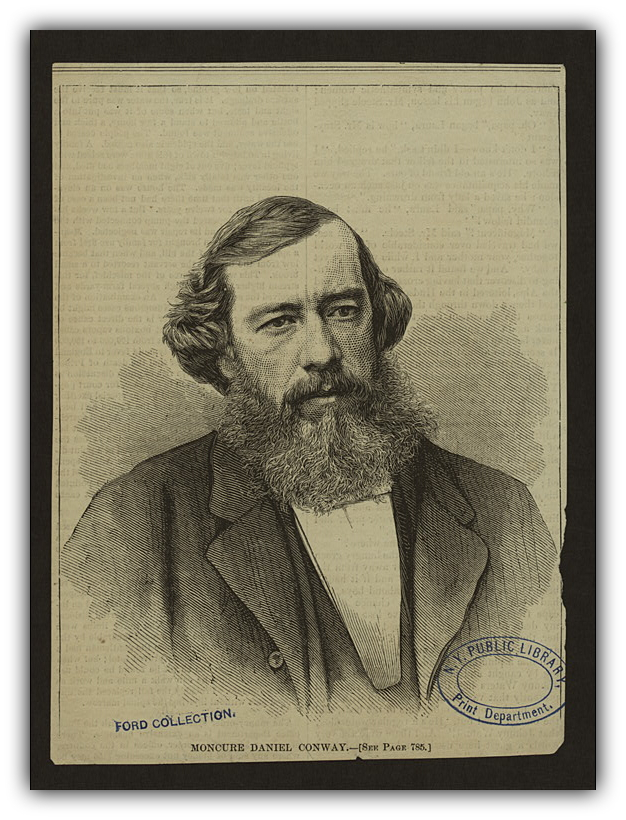

Moncure Conway and the Conway House

Falmouth’s residents included merchants, millers, and manufacturers. One such entrepreneur was James Vass, original owner of the Conway House.”2 Vass immigrated to Falmouth from Forres, Scotland.3 He was an influential and upstanding citizen of the town, serving as member and chairman of many organizations, associations, and committees throughout his lifetime.4 In addition to being a merchant of goods, Vass also owned a large wheat mill in town.5 As a leading businessman at the peak of Falmouth’s economic prosperity, Vass exhibited his success and influence by residing in the largest brick house in the town.6 It stood approximately 300 feet directly in front of Falmouth’s docks on the flood plain of the Rappahannock.7 This massive residential structure occupied a location clearly visible to passengers and tradesmen coming into the town. The house, grand in material and design, reflected an affluent inhabitant, and a prosperous community.

Falmouth’s prosperity declined as the Rappahannock River silted in, making the waters far too shallow for large ships to dock in the port town. Additionally, the first bridge was constructed crossing the Rappahannock in the early nineteenth century making two ports (Falmouth and Fredericksburg), one on either side of the river, unnecessary.8 These two factors essentially put an end to the growth of the town and effectively moved the center of commerce across the river from Falmouth to Fredericksburg. The economic base of the town began to dwindle, leaving residents to move their businesses across the river. Because the area’s economy was uncertain, residents were slow to finance grand homes such as the Conway House, which still remains grand in comparison to its surrounding buildings.

Although Falmouth’s growth as an important trading community had declined, the Conway House remained a distinguished residence for area citizens. William C. Beale, a close friend of Vass and wealthy fellow merchant, next purchased the home and lived there with his newlywed wife Jane Howison for the first few years of their marriage.9 Mrs. Beale, author of a journal recording her life in Falmouth from 1850 to 1862, writes that she spent five happy years in “that brick house on the bank of the river so shaded by trees.10 In 1838, Walker Peyton Conway purchased the property for his family.11 W. P. Conway, presiding justice of the Stafford County Court for over thirty years, and his wife, Margaret Daniel Conway, were devout Methodists and utilized a room in their basement as a place of worship.12 One of their sons, Moncure Daniel Conway, was a nineteenth-century internationally known author, lecturer, clergyman, and abolitionist.13

Moncure Conway the son of county magistrate Walker Peyton Conway, whose relatives included the families of former United States presidents James Madison and George Washington. His mother, Margaret Stone Daniel, was the granddaughter of Thomas Stone, Maryland signatory of the Declaration of Independence. An uncle, Judge Eustace Conway, served as an important states’ rights advocate in the Virginia General Assembly. His great uncle, Peter Vivian Daniel, was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (1842–1860) who sided with the majority in both the 1847 decision that affirmed the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and in the Dred Scott decision (1857), which ruled, in part, that African Americans could never become U.S. citizens.

His father was a wealthy slave-holding gentleman farmer, county judge, and state representative; his home, known as the Conway House, still stands at 305 King Street (also known as River Road), along the Rappahannock River. Although not an abolitionist or a formal supporter of woman’s rights, Margaret Conway, his mother, expressed moral reservations about slavery.

The Conway House was home to a family truly divided by the tragic struggle of the American Civil War. Walker Peyton Conway left Falmouth in the face of the advancing Union Army in April 1862, by crossing the river to Fredericksburg. Shortly afterward he supported the Confederacy by taking up residency in Richmond and engaging in the banking business.14 His wife, Margaret Daniel Conway, held antislavery views and went to live with their daughter Mildred and her husband in Pennsylvania.15 Moncure Daniel Conway was an abolitionist exiled from his home, while his two younger brothers served in the Confederate army. Peter Vivian Daniel Conway enlisted in the famous Fredericksburg Artillery.16 Richard Moncure Conway enlisted in the 5th Texas Infantry, and later joined Terry’s Texas Rangers (8th Texas Cavalry).17 The Conway family experienced a devastating division and separation by a tragedy of epic proportions.

Moncure Conway emerged as a rare abolitionist from the South. In Professor John d’Entrement’s biography of Conway, “There always had been a tension in Conway between his drive for independence and his need for interdependence, a compulsion to confront and a craving to reconcile, an impulse toward conflict and a longing for peace. For much of his life he had kept these competing needs balanced, though uneasily. The Civil War had disrupted the balance and forced him to take sides actively in the bloodiest conflict in American history. It had burdened him with the most macabre of ironies, compelling him to fight the violent subjugation of one people by violently subjugating another -his own people.”18

The following is taken from a manuscript by Moncure Conway, “Letter from Virginia,” October 1875.

“My old Virginian home… I departed 17 years ago under circumstances more grievous than any physical cloud or storm. I had offended against the despot slavery by thought and word, and the kindness of a few could not save me from the bitterness and wrath of the many. Under the threats of some who had once been my playmates and schoolmates I was compelled to leave the home of my parents, the land of my birth; and as I sailed away that day on the broad Potomac, and looked back on the state I passionately loved, its beauty was darkened by a sense of that impending tragedy which since has fallen upon it. On that soil of Virginia from which I was driven with heart full of love for those I was leaving, hosts were soon gathered with rifle and cannon. On the banks of that gentle and silvery river which to my childish eyes seemed far away from the great world, are now thirty thousand graves of young men who might have loved each other but for the remorseless decree of that fell power which held neither love nor life of value compared with its wild and guilty phantasy that man could hold property in man. These events have never changed my feeling towards my early home, my kindred, or even those who threatened me. I was never accustomed to look upon them in any other light than as more unhappy victims of a hereditary evil than I was. Their anger and alienation from me I traced beyond themselves to the tyrant institution which swayed with perpetual terror. It was perfectly true that even my poor presence was a danger. If human beings were to be held in bondage no one hostile to the wrong could move among them without danger of exciting the slaves to some outbreak. Fear can turn even soft hearts to stone. But I knew these hearts from infancy; and I knew that when the wrong was gone, and the danger, and the fear, they would again beat warm with love and generosity. And it was under this conviction that there drew within me that longing to revisit my old home which, for a space, has parted me from you.”19

During the Civil War the Conway House became a Union hospital in April 1862.20 Conway gives a fascinating account in his autobiography as follows:

“When the Union army under General McDowell entered Falmouth.. . The house was left empty and locked up, the house servants remaining in their abode in the back. Yet as the Union soldiers were filing past a shot was fired from a window of the Conway House, or from a comer of its yard, and a soldier wounded. It was never known who fired the shot; our Negroes assured me that the house was locked and watched. The Union soldiers alarmed and enraged, battered down the doors, and, finding no one, began vengeance on the furniture. It happened, however, that in my mother’s bedroom was hung a portrait of myself, and this caught the eye of a youth who had known me in Washington. He cried to his furious comrades to stop. The servants were called in, and were much relieved when they found that it was to speak of my portrait. Old Eliza cried, ‘It’s mars Monc the preacher, as good abolitionist as any of you!’. . . It was some consolation to me that, though long regarded as the black sheep of the family, my portrait saved Conway house from destruction, for that was contemplated. The house was of brick, and the largest in Falmouth; it was made a hospital, and the seriously wounded soldier was its first inmate…”

In the summer of 1862 Conway learned that about thirty of his father’s slaves had escaped to Washington, D.C. At great risk to himself he rushed to escort them to Ohio and posed for a time as their owner in the slave city of Baltimore. He helped to resettle the freed people on donated land near Yellow Springs, Ohio.

When describing the town of Falmouth when the Union Army entered it there can be no better source than the writings of Moncure Conway.

The Union Occupation of Falmouth that made John Washington’s freedom possible and a “Slave No More.”

Report of Brig. Gen. Christopher C. Augur, U.S. Army, commanding brigade.

CAMP OPPOSITE FREDERICKSBURG, VA., APRIL 18, 1862 – 12 M.

CAPTAIN: I have the honor to report the arrival on my command at this point at 7:30 o’clock this morning, but, I am sorry to say, not in time to save either of the bridges. All accounts agree in representing the bridges as being for several days prepared for burning, by having the cribs filled with light-wood and tar and shavings. These were lighted about a half hour before we came in sight of them, and after the enemy’s forces on this side of the Rappahannock had passed over. We could see a light battery, a regiment of cavalry, and one of infantry going to the rear as we arrived.

Our march has not been without incident. We came upon the first of the enemy’s pickets about 18 miles from Catlett’s Station, and were only defeated in capturing it by a little girl from a neighboring house discovering our men creeping through the woods and signaling them to the picket. I at the same time learned from some negroes and others that there was a camp of four companies of their cavalry near the Brick Church, about five miles from this place, and that a quantity of forage had just been sent there for their use. Although it would make my march a very long one, I determined, as they would learn from their driven-in pickets that we were on the road, to make an attempt to engage them at their camp, and, if practicable, to follow them immediately to Falmouth and try to save the bridges. I organized the light column as was suggested, and leaving Colonel Sullivan in command of the main body, pushed on. At arriving near their camp I directed the Harris Light Cavalry and one battalion of Bayard’s Pennsylvania cavalry, under Lieutenant-Colonel Kirkpatrick, to move rapidly forward and attack. This was handsomely done, and the camp and its forage and few horses captured.

I regret to report that Lieutenant Decker, of the Harris Light Cavalry, was killed in the charge. The enemy’s cavalry fell back about a mile upon a body of infantry. It being now quite dark, and the command very much fatigued by its long march of 26 miles, I determined to halt them some hours.

Some negroes taken in camp reported that an ambuscade had been prepared for us 2 miles in advance. Shortly after a citizen living in the vicinity came into my camp from Falmouth and reported the same thing, and that he had not been permitted to come up the main road, but had reached us by a by-road, on which there were no pickets, and which came into the main road near Falmouth, some 2 miles beyond the point to which they were reported as lying. He said he had left Falmouth just before sunset; that the bridge was prepared, as stated, for burning, and that he would conduct a command by the by-road and enable it to reach and save the bridge, and get in the rear of the enemy at the same time. I was satisfied from the reports of the negroes and from other evidence that he was a good Union man, and that it was advisable to venture the attempt, as I knew the desire of the general commanding the department to save the bridge.

I entrusted this enterprise to Colonel Bayard, of the First Pennsylvania Cavalry, who had one battalion of his regiment and two battalions of Harris Light Cavalry, under Lieutenant-Colonel Kilpatrick. He left me at 2 a.m. this morning. Unfortunately the enemy in the mean time changed his point of ambuscade to just beyond where the by-road entered the main road, where the command received a volley of about 200 infantry on the watch for them, and were then charged on by cavalry. The road had been barricaded, too, which prevented their farther advance. They wheeled and charged upon the infantry, killing and wounded several (the exact number not known) and capturing 1 man. Colonel Bayard extricated his command with a loss of 5 killed and 16 wounded and a loss of some 15 horses. Thus disappointed in my attempt to secure the bridge by surprise, I advanced at sunrise with my whole command prepared to fight, but with the exception of a few pickets, saw none of the enemy until my arrival at the river.

I am unable at this time to give you any reliable information on the points suggested in my instructions. I send this by the commandant of the squadron ordered to Aquia Creek per my instructions of yesterday. To-morrow I will send the entire train there with a battalion of cavalry.

I have no reason to believe Colonel Bayard was intentionally misled by our guide. for there is abundant evidence of his having suffered greatly in consequence of his Union sentiments.

I regret to add that our valuable scout (Britton) was severely wounded in the leg.

I am, captain, very respectfully, you obedient servant,

CC AUGUR, Brigadier-General, Commanding.

Capt. R. Chandler, A.A.G., Hdqrs. King’s Division, Catlett’s Station, VA.

Occupation of Fredericksburg – Important Action of the Citizens and City Councils, The Steamer St. Nicholas of Baltimore, Burned, Destruction of Railroad Bridges, &c.

ARRIVAL AT FALMOUTH

The command then drove the enemy’s forces, which fell back without further resistance, and which consisted of a regiment of infantry, one of cavalry and a battery of artillery, across the Rappahannock, but were unable to save the bridges, which were prepared for burning by having tar, shavings and light wood in the crib work, and which were fired as soon as the enemy crossed. They burnt the bridge used by the citizens, and also the Richmond and Fredericksburg Railroad bridge, one mile below.

The little town of Falmouth, on the north bank of the Rappahannock, immediately opposite Fredericksburg, was found almost entirely deserted. Several Union families remained to welcome the advance of our troops. The people generally received our soldiers in a friendly manner.

Our occupation of the place was a surprise. The mills were still running, and women and children engaged in ordinary domestic avocations when our cannon belched forth its thunder from the adjacent cliff.

General Augur and staff were courteously entertained by Mr. J. B. Ficklin, a wealthy citizen of Falmouth, whose loyalty rendered him obnoxious to the rebels.

Immediate preparations were made for the repair of the bridge, that had been only slightly damaged.

Washington, April 20 – Our forces under General Augur still occupy the heights of Falmouth, opposite and commanding the city of Fredericksburg.

From the citizens of Fredericksburg, who have crossed over to Falmouth by means of small skiffs, much valuable information has been derived. Most of these affirm that as soon as we take possession of the city, and there is no fear of the return of the rebels, a majority of the remaining citizens will be found loyal.

The railroad to Fredericksburg, with the exception of a mile of the track which had been taken up, and the loss of two bridges, easily reconstructed, is in good order.

The railroad bridge over the Rappahannock will require a considerable length of time to be repaired, as the piers are very high and wide apart.

- John Washington’s Civil War: A Slave Narrative by Washington, John, 1838-1918 – Edited Crandall Shifflett ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), p. 11. See also Stafford County Deed Book AA, pp. 268-270. ↩︎

- Correspondence between Mr. & Mrs. Norman L. Schools and James Vass’s great-great grandson, Lachlan Maury Vass, Jr., 102 Grande Hills Blvd., Bush, LA, November 18, 2002. ↩︎

- Various articles from the Fredericksburg Newspaper Virginia Herald name Vass as a merchant selling goods (5/21/1802); bank director (1/1/1807); Commissioner of the Falmouth canal project (8/5/1815); on the board for the Female Charity School (3/11/1820); on the Falmouth school board (12/17/1825); as well as owning the Thistle Mill (9/16/1812). ↩︎

- Johnson, John Janney, “The Falmouth Canal and Its Mills: An Industrial History,” The Journal of Fredericksburg History, vol. 2, (Fredericksburg, VA, Billingsley Printing and Engraving for Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc., 1997), p. 28. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), p. 11. ↩︎

- Eby, Jerrilynn, They Called Stafford Home: The Development of Stafford County, Virginia from 1600 until 1865, (Bowie, MD, Heritage Books, Inc., 1997), p. 298. ↩︎

- Felder, Paula S., “The Falmouth Story: A View From the Twentieth Century,” Fredericksburg, VA: Historic Publications of Fredericksburg, p. 5. ↩︎

- Stafford County Deed Book C O B, p. 306. ↩︎

- Beale, Jane Howison, The Journal of Jane Howison Beale, (n.p., 1995), For Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, Inc., p. 20. Jane Howison Beale’s journal covers the period 1850 to 1862 after the Beale family had taken up its new residency in the town of Fredericksburg. This journal provides a dramatic detailed account of her experiences during the battle of Fredericksburg. Interestingly on page 91 she records a personal visit from Mrs. W. P. Conway, the mother of Moncure Daniel Conway ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, Vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), 1904 ↩︎

- d’Entremont, John, Southern Emancipator: Moncure Daniel Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865 (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1987), pp. 5, 24-25. “Although most of the Methodist classes were segregated by sex, church records from 1846 show the class at Conway House to have been the only one composed of both sexes. Its thirteen women and six men reflected the sexual composition of the congregation as a whole.” For an additional account see Conway’s Autobiography, Memoirs and Experiences vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), pp. 19-20, where he writes, “.. .the basement of my father’s house in Falmouth was fitted up for evening prayer – meetings, which were held there twice every week.” In addition, “Some of those gathered in the basement he (Conway’s father) had picked up out of the ditch…. As I sang in the basement second treble to my mother, I dreamed of the distant beauties of Palestine, though the cedars of Lebanon were thick on our Falmouth hills, and no rose of Sharon ever equaled those of our garden. The wondrous Judas – tree at our door, and fig – trees, myrtles, fireflies, meadows, crystal streams, all the materials of a paradise were around me while I sang of things far off and never to be attained.” ↩︎

- Eby, Jerrilynn, They Called Stafford Home: The Development of Stafford County, Virginia from 1600 until 1865, (Bowie, MD, Heritage Books, Inc., 1997), p. 299. In another source. Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), pp. 190-191, Conway describes a harrowing experience in 1855, when he ” .. went up with a light heart to my dear old home in Falmouth…. Next morning as I was walking through the main street a number of young men. some of them former schoolmates, hailed me and surrounded me; they told me that my presence in Falmouth could not be tolerated. ‘There is danger to have that kind of man among our servants, and you must leave.’ By this time a number of the rougher sort had crowed up and there were threats. Then a friendlier voice said on account of their respect for my parents and family they wished to avoid violence, and hoped that I would leave…. It was a heavy moment when I left…. It was exile.” For a summary of Moncure Conway’s life and achievements see “Who Was Moncure Conway,” South Place Ethical Society, Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, London, WCIR 4RL. For an in depth work of Moncure Conway see d’Entremont, John, Southern Emancipator: Moncure Daniel Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865, (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1987). Mr. d’Entremont is Associate Professor of History at Randolph-Macon Woman’s College. His study of Moncure Conway received the Allan Nevins Prize of the Society of American Historians. ↩︎

- Hayden, Horace E., Virginia Genealogies, (Baltimore MD, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1979) p.284 ↩︎

- d’Entremont, John, Southern Emancipator: Moncure Daniel Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865, (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 152. ↩︎

- Krick, Robert K., Fredericksburg Artillery, (Lynchburg, VA, H E. Howard, Inc., 1986), p. 99. In addition d’Entremont, John, Southern Emancipator, (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 217 states that “The war had been hard on him (P. V.D. Conway), dealing him a nearly fatal bout with typhoid plus a leg shattered by an artillery shell. But he had survived, and now wore his wound as a badge of honor.” ↩︎

- Hayden, Horace E., Virginia Genealogies, (Baltimore, MD, Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1979), p. 287. According to Civil War Research and Genealogy Database, Historical Data System, Inc., the 5th Texas Infantry was assigned to the Department of Northern Virginia in the early part of the war. Its Division assignment was located at Dumfries, Virginia, just north of Stafford County. This may be the reason for Richard Conway joining a Texas organization. ↩︎

- d’Entremont, John, Southern Emancipator: Moncure Daniel Conway: The American Years, 1832-1865, (New York, NY, Oxford University Press, 1987), p. 219. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, “Letter from Virginia, October 1875,” Columbia University Libraries, Special Collections, Manhattan, New York, NY. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel, Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway, vol. 1, (New York, NY, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1904), p. 11. Conway states that the house was used as a hospital 1862 – 1865. An additional reference by Conway appears in ” Hunting a Mythical Pall Bearer,” Harper’s New Monthlv Magazine, vol. LXXII. (New York, NY, Harpers & Brothers Publishers, 1886) p. 211. For an account of the first occupation of Falmouth by Union troops see Noel G. Harmon’s Fredericksburg Civil War Sites, (Lynchburg, VA, H. E. Howard, Inc., 1995), pp. 68-69. Additionally, there is evidence in the Conway House that spikes and Civil War bayonets were driven into the back of two fireplaces and the back of a built-in closet and utilized as hangers by the soldiers. ↩︎