There was never a doubt, when we saw this Church on the National Register of Historic Places, that we would visit. This is a Church that has a long and complex history. It also has an unusual but sad ending. The Falmouth Union Church and Cemetery sits on approximately three acres. It contains the archaeological sites of the 1733 and 1750s Falmouth Anglican churches and the standing remains of the circa 1819 Union Church. The narthex of the Union Church, 40 feet wide by 10 feet in depth with the rear bricked up, is what remains of the original structure. It was most fascinating standing in front of it and imaging just walking up this Sunday, walking up to the front door and walking in for the service. So now we will tell you why you cannot do that this Sunday.

With a long history, nonetheless, Union Church, by 1935 had ceased to exist as a church body. The destructive storm of 1950, which is described below left collapsed walls and the roof. Without a vibrant, committed congregation there was little chance of it being rebuilt. Mentioned below is an effort by the Falmouth Civic Improvement Club to restore, however that was cancelled after the storm. This church, which since 1733 had reflected the Falmouth community and its history, would never be rebuilt as a functioning Church, however it would be saved as a landmark by being entered on the Register of Historic Places and by an organization called Union Church Preservation Project. After exploring the preservation effort, we will delve into the rich history of the Church through excerpts from the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.

Fredericksburg, VA Mon, Sep 11, 1950 ·Page 2

Heavy weekend rain apparently washed out all chances of restoring old Union Church in Falmouth.

Pounded and weakened by the torrential downpours, what was left of the roof of the historic building collapsed last night about 6:30 and down with it went the southern wall of Flemish brick.

Union Church, probably more than 200 years old, crowns the hilltop east of Falmouth and overlooks the village. It is believed that George Washington went to school conducted in the building by Master Hobby, a minister. The edifice also was used as a hospital for Federal troops during the War Between the States.

The Falmouth Civic Improvement Club, headed by Mrs. Thomas S. Morrison as president, had raised $1,200 toward the construction of a roof estimated to cost about $2,500 as the first step toward restoration.

Several hundred dollars of this came from individual donors whose gifts will be returned. The rest, raised by various benefits, may be used for the upkeep of the Falmouth cemetery and a clubhouse.

“Union Church Preservation Project”

As mentioned in The Free Lance-Star article the first attempt to renovate the church was by The Falmouth Civic Improvement Club prior to the storm. Virginia’s Most Endangered Historic Places Listed Union Church in 2006. It was listed because since the 1950s, little had been done to preserve the remaining structure with the exception of the remaining narthex being enclosed with brick to help preserve the interior of the building. Weather is still a major threat, specifically to the roof and bell tower, which still houses a bell from 1867 (the original bell was damaged in the Civil War). In 2009, a nonprofit group known as the Trustees of the Union Church Historic Site was formed to advocate for the preservation of the remaining structure. As recently as 2012, the Trustees were able to fix the numerous holes in the roof. In preparation for these repairs, the bell, which was in significant danger of falling and causing additional damage, was removed and put on display in the Stafford County Administration Building. In March 2013, one of the original pews from the church was donated to the Smithsonian Museum to be part of an exhibit at one of its newest museums the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The Union Church Preservation Project, a 501(c)3 nonprofit, was formed committed to preserving the structure and interpreting Union Church’s history. In an article in The Free Lance-Star dated July 29, 2019, they reported the following:

“After 200 years, Falmouth’s Union Church finally has a new bell tower. Early Thursday morning, a refurbished, 4,400-pound belfry was carefully craned directly over the historic Carter Street church in Stafford County. By 9:30 a.m., with guidance from workers positioned high atop the church, the crane operator slowly lowered the Colonial-era bell tower into place, precisely where the original had sat since 1819.

The following pictures are from their Facebook page.

On June 14th, 2019: In honor of the church’s bicentennial (1819-2019), a very generous donor has agreed to pay for a large preservation project at the church. It is by no means a complete overhaul, but it will certainly ensure that the church remains standing! Here are some of the pictures that went with the post.

The following, excluding photos, but including text and footnoted items, unless otherwise noted, have been taken from the:

THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM

The Falmouth Anglican Church

The earliest site was utilized solely by the Church of England. The town of Falmouth was created by act of the Virginia General Assembly in the year 1727. The said act called for parcels to be set aside for a “church and church yard.”1 At that time Falmouth was originally part of King George County and within Hanover (Hannover) Parish.2 A 1732 act of the Virginia Assembly split Hanover Parish with the upper part becoming a new parish named Brunswick. Accordingly, this same act called for “placing of the church of the said new parish of Brunswick…to be erected in the town of Falmouth, on the lot set apart for that purpose.”3

This first structure on the site was the Falmouth Anglican Church built in 1733 or shortly thereafter as a cruciform timber frame structure.4 It was located in an area that is part of the cemetery today. A ground feature exists, commonly referred to traditionally as where the old church was located, and appears centrally within the original boundaries of the “church and church yard.” A further indication of its location may be gathered from a newspaper article dated 1819 which states that the old Church is in “the Old Yard”, referring to the cemetery.5 The Historiographer of the Diocese of Virginia noted in 1916 “an old overgrown graveyard …covers the site of the first church.”6 Having no surviving above ground evidence, the site is an important archaeological site.

The Church’s Cemetery

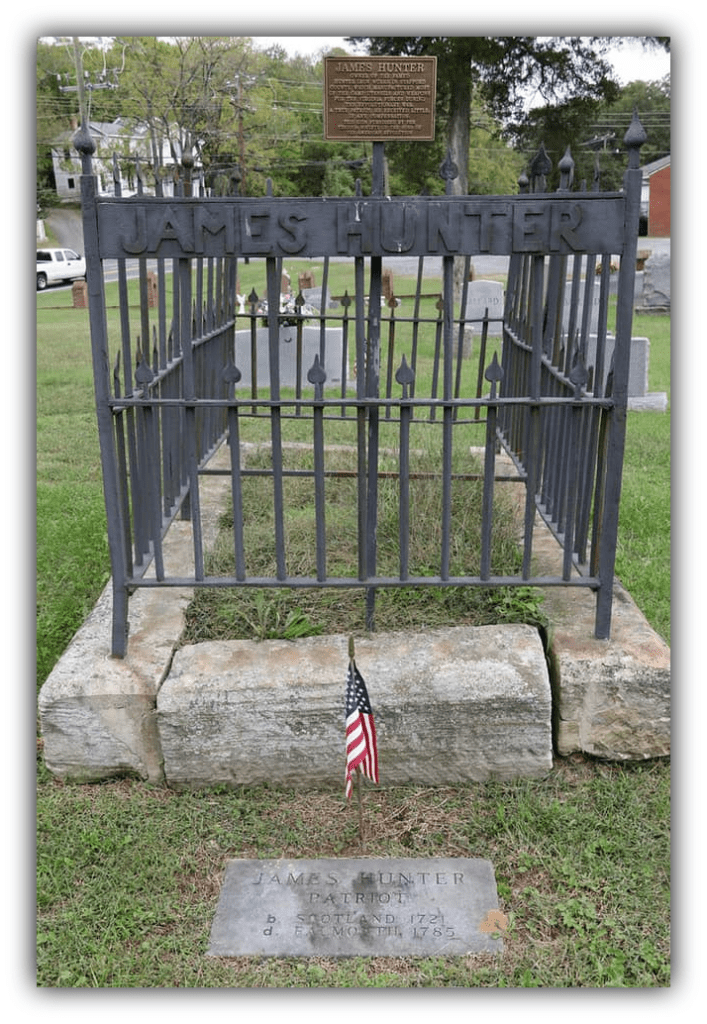

The Union Church Cemetery, also known as the Falmouth Cemetery, contains many early grave markers of hand-cut stone, some ornately carved, and with a few instances of funerary art. Among the graves of prominent individuals is the grave of James Hunter, owner of the eighteenth-century ironworks located nearby, which is surrounded by early wrought-iron fencing.7 The cemetery contains African-American graves, many of which are unmarked.8

The Union Church Cemetery became a burying ground during the Civil War starting with the burial of the soldiers killed in a skirmish on April 17-18, 1862, resulting in the first occupation of Falmouth by Union troops between April and August, 1862.9 Interments continued as the church and later the adjacent Conway House were utilized as hospitals10 and as soldiers died of their wounds resulting from the battles of Fredericksburg (1862), Chancellorsville, including 2nd Fredericksburg (1863), the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania Court House (1864). During the winter and spring of 1862-1863 the Union army occupied Stafford County including Falmouth and many deaths resulted from disease and the harsh winter. At the end of the war in 1865 part of the Union army commanded by General William T. Sherman marched from North Carolina to Washington stopping in Falmouth, again bringing convalescing wounded and sick soldiers. Given an accumulative 12 months or more of occupation and four major battles, the area was probably inundated with corpses needing burial.11 Nonetheless, no above-ground evidence remains today of Civil War interments in the Union Church Cemetery.

Soldiers’ graves were later moved to the Fredericksburg National Cemetery; however, it would not be uncommon to miss makeshift and unidentified graves. The names of twenty-four Union soldiers have been identified as buried in the Union Church Cemetery.12 Eighteen identified Union burials and thirty-nine unidentified soldier burials were recovered and re-interred in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery.13 Oral tradition contends there is an unmarked Confederate mass grave in the cemetery possibly from prisoner death or due to sickness when the area was Confederate occupied; however, there is no evidence to substantiate this claim.

Wisconsin soldiers reportedly desecrated graves in the cemetery in search of jewelry which had been buried with corpses, as a source of barter with army sutlers in the town of Falmouth. Soldiers vandalized existing markers for material to make makeshift memorials for their own dead.14 Headstones may have been utilized as makeshift fire hearths for winter huts during the 1862-63 winter occupation. The potential for many unmarked graves is significantly high.

An older section of the cemetery is situated northeast of the Union Church and contextually associated with the first Falmouth Anglican Church site. An apparent wide and odd distribution of earlier grave markers seems to indicate the probability that existing unmarked burials lay in between. Random low protruding stones without inscriptions may indicate a headstone or a plot boundary marker. This area contains one raised horizontal stone tablet and six horizontal stone tablets at grade.

The area of the cemetery that declines at the southeast corner contains fill dirt material deposited in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s.15 In an oral interview with an aged resident it was related this less desirable area was an early burial ground for African Americans. After the fill dirt was deposited “white” graves were placed above and over top of the African American graves.16

An oral interview with an elderly trustee of the cemetery identified an additional area of unmarked African-American graves in what would be considered the outer fringe of the cemetery. This area was pointed out as parallel and adjacent to current Butler Road and with some extension from the northeast corner southward. A deep ravine along the east side extended southward toward the river. Filled in around 1940, the area currently serves as a parking lot for the Ray Grizzold Community Center, formally an old Falmouth school building.17 The area identified as containing unmarked African-American graves includes two of the only three identified African-American graves within the cemetery.

An area of the cemetery closer to the Union Church contains predominately late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century graves, many of which are contained in separately maintained family burial plots evidently created in the post-Civil War era. Some of these plots are enclosed with some kind of small low concrete wall. A date of 1920 is scratched in one wall surface and would be fairly indicative of the time period during which these little enclosures were popular. One enclosure has a well-laid mortared stone wall with an iron gate, while another enclosure features round iron pipes. Enclosed or not, the appearance of these plots is neat and orderly.

In this area what can be termed “depression era” grave markers are found. These were made by a family member or by someone known locally who was skilled at making them. Cement would be mixed with gravel and poured into a mold simply made from carving out earth in the form of a grave stone, then smoothed over by a board. Smaller in mass, the markers had simply curved tops and were all that could be afforded by some residents. Several indicate an attempt was made to scratch an inscription on them; however, these inscriptions are all illegible today.

Grave markers of stone window sills appear as a convenient source of architectural elements salvaged from Falmouth’s abandoned structures or those damaged during the Civil War. Since the cemetery has remained in continual use, it contains the graves of veterans of American wars and conflicts from the American Revolution through the Vietnam War.

The cemetery is elevated along present day Butler Road and atop this area is placed an artillery gun dating from the first half of the twentieth century, pointed toward the road.18 In front of this artillery gun is a horizontal tablet denoting its donation to the Falmouth Cemetery by the U.S. Navy in 1963. This is accompanied by a tall flag staff proudly flying the American flag for the community. A ground light illuminates the flag at night. A modern brick two tiered raised platform with a tablet reads:

IN MEMORIAM IN MEMORY OF THOSE WHO LIE ON THIS HISTORIC HILL WHERE TIME AND NATURE HAVE ERASED ALL EVIDENCE OF THEIR FINAL RESTING PLACE FOUNDED 1727

A modern utility shed of portable type and barn shape is presently located at the back of the cemetery (south boundary). It is used for grounds keeping implements and storage of a riding lawn mower. The east boundary was previously identified by modern post and wire cable fencing running its length until, in 2007, it was replaced with a low brick wall containing intermittent brick columns. This low wall was designed to enable visitors to easily step over it. The wall was built with reproduction oversized brick using colored mortar and tooled joints. Within the cemetery are twenty-two tall stately cedar trees.

Prominent Graves

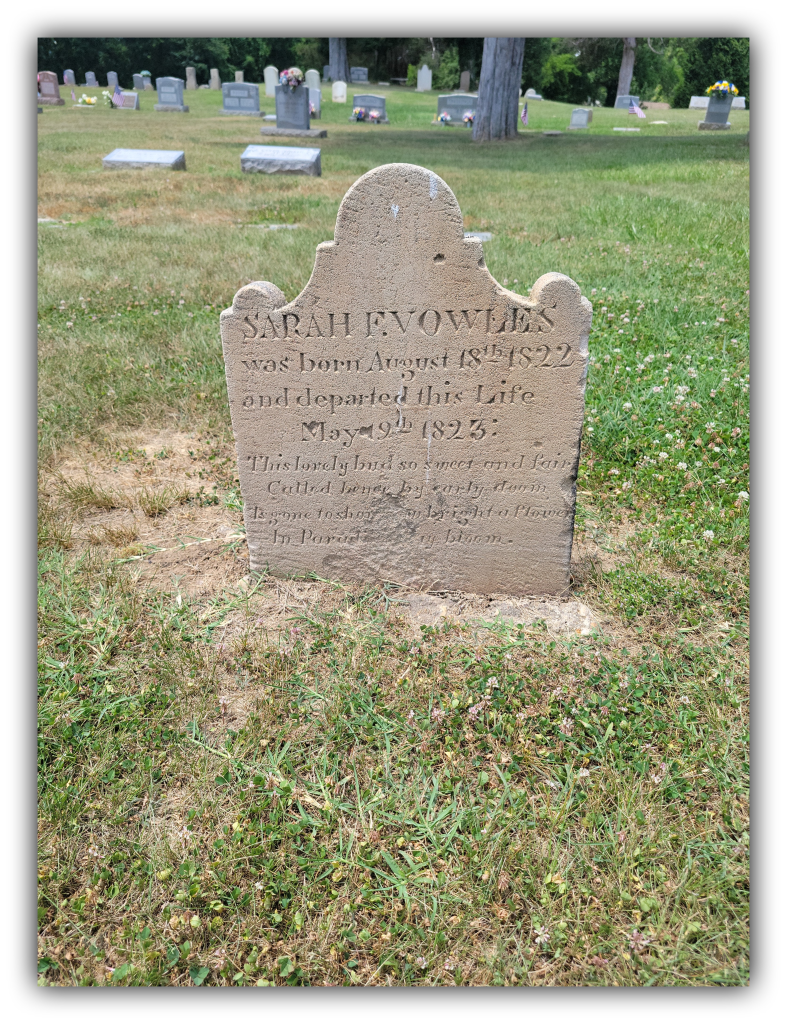

Three example grave stones have been chosen to demonstrate the cosmopolitan nature of Falmouth at an early period in its history. One grave stone is for an industrialist, one for an African American, and the last for an exile.

The first grave is enclosed with early wrought iron fencing and a twentieth-century plaque bearing the inscription:

James Hunter was the owner and operator of the Hunter Iron Works at Falmouth, which provided the overwhelming majority of muskets and iron cooking implements for the Virginia troops in the Revolutionary War. He produced: muskets, rifles, bayonets, swords, pistols, and large-bore wall guns. For the Virginia Navy he produced: anchors and ship fittings. He outfitted the Virginia troops who played a vital role in the Battle of Cowpens, and also those who were at Yorktown. Hunter’s Iron Works were so valuable that Governor Thomas Jefferson ordered special military protection for the industry. Hunter was never adequately paid for his services and he suffered serious financial setbacks as a result. James Hunter sacrificed his fortune for the cause of independence and is considered a true patriot.

The site of the Hunter Iron Works is situated on the Stafford County side of the Rappahannock River slightly upstream from Falmouth. It was listed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

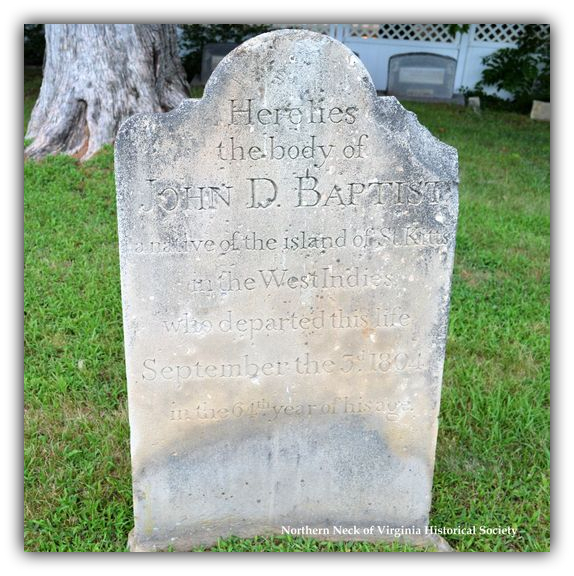

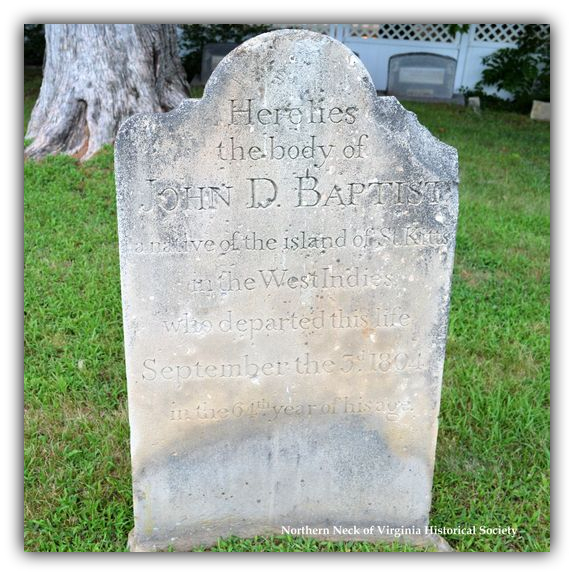

The second grave is that of John D. Baptist and has a stone with the following inscription:

Here lies the body of John D. Baptist a native of the island of St. Kitts in the West Indies. who departed this life September the 3d. 1804 in the 64th year of his age.

The following is taken from “African American History in the Rappahannock Region”:

John DeBaptiste…served as a sailor on board Fielding Lewis’ ship, The Dragon, which patrolled the Rappahannock River and parts of the Chesapeake Bay during the Revolutionary War. The Dragon was built in Fredericksburg in 1777. She had the distinction of having more African-Americans serve on her than any other ship during that time period. John DeBaptiste, a native of St. Kitts, served on The Dragon which later saw action in the Chesapeake Bay. He was later prominent in local business, owning much property and running the ferry at Falmouth.

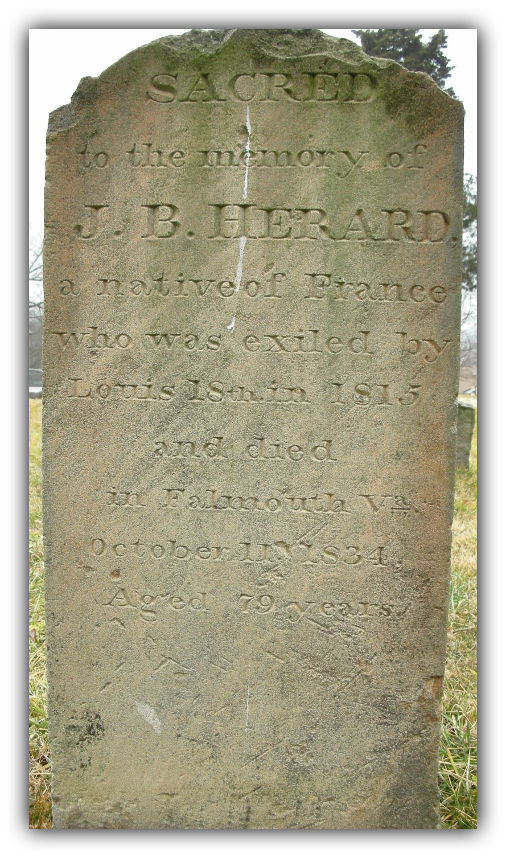

The third grave is that of J.B. Herard and has a stone with the following inscription:

SACRED to the memory of J. B. HERARD a native of France who was exiled by Louis 18th. in 1815 and died in Falmouth Va. October 11. 1834. Aged 79 years.

Herard must have found Falmouth a safe haven. He is reported to have been “one of the officers of Napoleon, a French nobleman, Count Herard, who fought through all the Napoleon wars…He and Lafayette embraced and kissed each other when they met on the occasion of Lafayette’s visit here in 1824.”19

Early Falmouth and Union Church History

The town of Falmouth was created by act of the General Assembly in 1727. This act instructed the town trustees to provide for a church and church yard and the site chosen, located in the northeastern section of the town, became known as “Church Hill” and the street running by the church was renamed “Church Street.” The placement of an elaborate church and cemetery on a hill overlooking the town is indicative of ecclesiastical practices in the early eighteenth century, as such placement “mystified the physical embodiments of religious ideology by setting it dramatically apart from ordinary people’s experiences.”20 The earliest church structure and cemetery are associated with the Carter family whose boxed pew was emblazoned with the Carter family coat of arms.21 This was no doubt for Charles Carter, son of Robert “King” Carter, father and son being original trustees of Falmouth town. Since the Carter family was the driving force behind the conception of the town of Falmouth, the first church built in cruciform plan may have been patterned after Christ Church in Lancaster County. As occurred in the first Christ Church, built by John Carter, the wooden form in Falmouth may have been intended for replacement by a brick cruciform church. As his father exerted a heavy-handed influence over Christ Church, Charles Carter probably did the same over the first Falmouth Church.

During the early to mid-eighteenth century, Falmouth reached a turning point with regard to a decline in its fortunes and population, while its neighbor across the river, Fredericksburg, grew and prospered. Robert “King” Carter died in 1732 and Charles Carter had moved away by 1752, leaving the General Assembly to act on behalf of the townspeople in stating that it was “necessary and expedient that the said town of Falmouth be supported and maintained, and the bounds and streets thereof properly ascertained.”22 Since all of the original town’s trustees had died except for Charles Carter, the General Assembly appointed new trustees, including Carter.23 The original wooden church structure may have suffered due to Falmouth’s economic decline during the mid-eighteenth century. Not long after the General Assembly acted on behalf of the townspeople and appointed new trustees, a second brick church was built between 1755 and 1760. This second brick church was built approximately 200 feet southwest of the wooden church.24

The American Revolution

Prior to the American Revolution the Anglican Church of England was the established church by law, supported by taxes and requiring all office holders in government to be Anglican.25 The Anglican Church spread along the length of the Atlantic seaboard with the largest concentration of congregants in the coastal South. The Church of England had an hierarchical form of governmental rule through ascending bodies of clergy, headed by bishops and archbishops. Virginia did not have a bishop, resulting in the gentry class dominating the church vestry. This arrangement allowed them to influence church affairs and enhance their power in the community. The Anglicans “have always favored elegantly constructed churches with ornately decorated interiors. The purpose of all this outward show is to instill those attending worship with a sense of awe and piety.”26

During the mid-eighteenth century the Great Awakening spread throughout British North America and popular support for Anglicanism suffered, while more evangelical Protestant congregations increased. The struggle for religious freedom paralleled the struggle for political freedom. In early December 1776 the Virginia Assembly passed an act stating:

That all and every Act of Parliament, by whatever title known and distinguished, which rendered criminal the maintaining any opinions in matters of religion, forbearing to repair to church or the exercising any mode of worship whatever, or which prescribes punishments for the same, shall henceforth be of no validity within this commonwealth. Whereas there are within this commonwealth great numbers of dissenters from the church established by law, who have heretofore been taxed for its support…Be it enacted,…That all dissenters from the said church shall from and after the passing of this Act, be totally free and exempt from all levies and impositions whatever towards supporting and maintaining the said church as it is now, or hereafter may be, established, and its ministers.27

The Disestablishment of the Episcopal Church in Virginia

Beginning in 1778-1779 the Virginia General Assembly started receiving petitions for complete disestablishment of the Anglican Church.28 Thomas Jefferson’s Statute of Religious Freedom, adopted January 16, 1786, ended all establishment of the Anglican Church in Virginia. During the American Revolution the second Falmouth Anglican Church witnessed a historic scene below the heights and at the river. An historian’s account follows:

General Count de Rochambeau and French troops transited Stafford in mid-September 1781. In fact, French Army troops of Rochambeau twice used Falmouth ford. Gen. George Washington, in New York, planned use of the 5,000 man French expeditionary force. When he became aware the French fleet was headed for the Chesapeake from the West Indies, he directed his forces to the Virginia Peninsula. Washington wrote to Rochambeau and his Continental troops on the march south: ‘From (Georgetown) a rout must be pursued to Fredericksburg, that will avoid an inconvenient ferry over Occoquan, and Rappahannock river at the Town of Fredericksburg. The latter may, I believe, be forded at Falmouth…’ After the Yorktown victory in October 1781, Washington and his French allies moved north through Falmouth. A French engineer sketched the ford at Falmouth. It is estimated that 4,000 French troops and 2,500 Continentals crossed at the ford.29

A French officer associated with Rochambeau’s troops passing through Falmouth in 1781-1782 noted visits to “a rather fine Protestant Church…”30

Nationhood and Antebellum Period

Falmouth was described in 1795 as “three quarters of a mile above Fredericksburg. It is irregularly built, and contains about 150 dwellings, and an Episcopalian Church.”31 The last rector of Brunswick Parish was Rev. Alexander MacFarland (or McFarlane) who was rector from 1792-1796.32 The Anglican Church transformed itself into the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States in 1789 and may have utilized the second Falmouth Anglican Church before it burned about 1818 according to a historiographer of the Diocese of Virginia.33 The probable dual use of the church by Episcopalians and other Protestants would have led to the structure being rebuilt by the community as a union church, one that was used by several different Protestant congregations.

The Union Church, built after the second Falmouth Anglican Church burned about 1818, is mentioned in the Virginia Herald in 1819 as “the erection of the new one …to be used by Christian Preachers of different denominations in all respects as heretofore.”34 The Union Church is depicted on a beaded purse attributed to a Falmouth resident and the belfry is shown displaying a French flag on the occasion of Lafayette’s visit to Falmouth and Fredericksburg in 1824.35 In Joseph Martin’s Gazeteer of 1835, the town is described as having “1 house of public worship free for all denominations…”36 From an account of childhood memories written by a visiting relative of a Falmouth family in the 1840s, the author states, “There was a church in Falmouth, of no particular denomination, open to the services of all, having been built by the common consent and contributions of the citizens… It had taken the place of an older structure and there was an old grave yard near by…”37

In 1851 the Union Church was the scene of one of the earliest sermons of the abolitionist Moncure Conway. He later was compelled to leave Falmouth under threat of bodily harm in 1854. Conway would later become the most outspoken and radical abolitionist produced by the South, causing him to be dismissed by a church in Washington, D.C. in 1856 and compelled to leave another in Cincinnati, Ohio. In his autobiography, Conway wrote:

The only church in Falmouth was (and is) a “union” house. Catholics and Unitarians were unknown in our region, and I remember no Episcopalian service in Falmouth; but between Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians the village had two and sometimes three sermons every Sunday. Now and then some peripatetic propagandist appeared. I remember the impression made on me by a female preacher, the only one I ever heard in Virginia. A good-looking man sat beside her in the pulpit, but uttered no word; the lady—middle-aged, refined, comely—arose without hymn or prayer, laid aside her gray poke-bonnet, and gave her sermon, of which I remember the sweet voice and engaging simplicity. I also remember that a hypercritical uncle, Dr. J. H. Daniel, praised the sermon.

The walls in the vestibule of Falmouth church were thickly covered with caricatures of various preachers and leading citizens penciled by irreverent youth while waiting to escort the ladies home. Probably the contrarious dogmas set forth from a “union” pulpit may have had a tendency to keep clever youths from taking any of them seriously.

Among our elders there was a keen interest in the controversies which I think must have usually characterized the sermons…. The congregations in Falmouth included the elite, but it was different in the Methodist conventicle in Fredericksburg.” He continued “….but the culminating event was my sermon in our own town, Falmouth. How often had I sat in that building listening to sermons—Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian—occasionally falling under the spell of some orator who made me think its pulpit the summit of the world! How large that church in my childhood, and how grand its assemblage of all the beauty and wealth of the neighborhood!38

Moncure Conway also provided an illustration of African Americans worshiping in Falmouth during this period:

The immersion of the colored people was always a picturesque and affecting scene. Dressed in white cotton…they moved under the Sunday morning sunshine across the sands opposite our house to the river, and there sang gently and sweetly. There was no noise or shouting. The rite was performed by a white minister. After immersion each was embraced by his or her relatives. There was more singing, and the procession moved slowly away.39

The Union Church Cemetery contains areas of African-American burials identified through oral tradition. Although unmarked and located along what was considered at the time the less prominent rear or sides of the cemetery, many of these graves probably date to the antebellum period.

The Union Church is a classic example of a southern church built with two distinct architectural components associated with African-American attendance. A balcony story is accessed by a narrow winding stairway inside the narthex against its left side interior wall. It was traditional in southern churches to have a balcony used as seating for slaves and free blacks and two separate front entrances–one used by slaves and free blacks and the other one used by white congregants. Since the access to the balcony was located to the left inside wall, slaves and free blacks would enter by the left entrance. Additionally, by incorporating the stairway in the narthex, separated from the sanctuary, the church’s floor plan minimized contact between the races. Other southern churches with a single front entrance incorporated a side door for this purpose.

During the antebellum period slaves and free blacks could not own church property; however, if a building was provided or given to them for purposes of worship, it had to have white trustees. In addition, an African-American congregation had to have a white minister. As there was no African-American church in Falmouth before the Civil War, most African-American residents probably attended Union Church.

The Civil War, 1861-1865

The Union Church and cemetery are strongly associated with the Civil War. The church itself was much used by Union troops during the conflict. The first occupation of Falmouth by Union forces occurred on the morning of April 18, 1862. Prior to this occupation a skirmish took place just above the village in which a Union officer was killed and the next day six other soldiers were killed and sixteen wounded. On April 23, 1862, a newspaper correspondent witnessed the following scene: “In the village of Falmouth there is one church which after the skirmish was used as a hospital. Stains of blood now cover it; some of the pews still remain; the floor near the pulpit is strewn with torn leaves from hymnbooks the remnants of the Falmouth S.S. Library. In the belfry the bell remains; the citizens not having responded to Beauregard a cry for bell metal.”40

The church bell would later disappear, apparently seized by Federal authorities and melted down for ordnance. In a post-war account, Walker P. Conway, a leading citizen whose property adjoined the Union Church, wrote to a niece that the church was used as a hospital during the war.41 There are no known accounts of citizens worshiping in the structure from this point until 1868. No accounts are found of soldiers attending services in the Union Church, as they did in other churches across the river in Fredericksburg.

The events of April 17-18, 1862 would also affect the town in another manner–Union soldiers would be interred within the town’s cemetery behind Union Church. On April 18 a slave named John Washington from Fredericksburg emancipated himself by crossing the Rappahannock River just above the Union Church, entering Union lines. In a post-war narrative, he remembers that on the early morning of April 19, 1862:

The soldiers had a sad duty to perform…The funeral was one of the most solemn and impressive I had ever witnessed in my life before. Their company (cavalry) was dismounted and drawn up in lines, around the seven new graves which had been dug side-by-side. The old Family Burying Ground wherein these new made graves had been dug contained the bones [of] some of the oldest and most wealthy of the Early Settlers of Falmouth. On some of the tombstones could be dimly traced the birthplaces of some in England, Scotland, and Wales as well as Ireland. And amidst grand old tombs and vaults, surrounded by noble cedars through which the April wind seemed to moan low dirges, there they was now about to deposit the remains of (what the rebels was pleased to term) the low born ‘Yankee’.

Side-by-side they rested those seven coffins on the edge of these seven new made graves. While the chaplain’s fervent prayer was wafted to the skies and after a hymn (Windham) had been sung those seven coffins was lowered to their final resting place. And amidst the sound of the earth falling into those new made graves, the ‘Band’ of Harris Light Cavalry broke forth in dear old ‘Pleyal Hymn’ and when those graves were finished there was scarcely a dry eye present. And with heavy hearts their company left that little burying ground some swearing to avenge their deaths.42

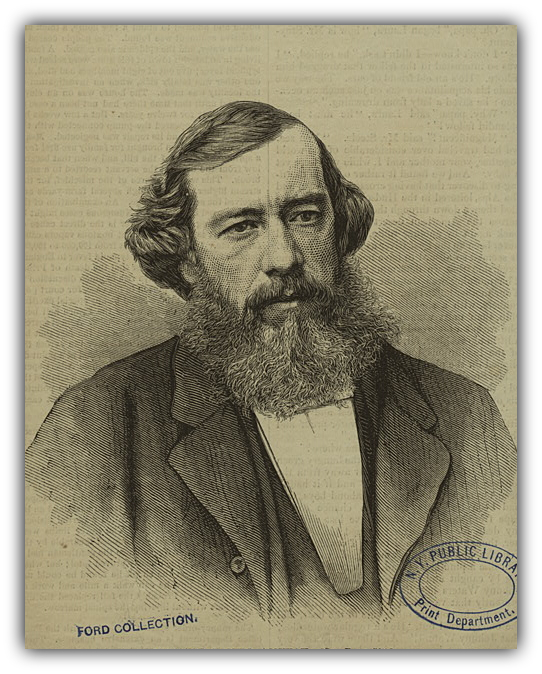

In another account, Lt. Charles Morton of the 2nd New York Cavalry writes home, “…the men that were killed were buried on Saturday with all the honors of war, escorted by the two regiments of cavalry and 14th Brooklyn.”43 Of the seven bodies interred, two were identified as being moved to the National Cemetery in Fredericksburg after the war. As un-identified remains were also moved, it can be assumed the other five remains were re-interred in Fredericksburg. All seven soldiers fallen on April 17-18, 1862 are known by name, and a carte de visite image exists of the officer killed, Lt. James Nelson Decker.44

Another soldier would die as a result of his wound and was described by Wyman S. White, a member of the 2nd United States Sharpshooters, “with his bowels protruding from a saber wound, still alive and conscious.”45 His companions erected a memorial “to the graves of those who fell in the advance on this place” with materials obtained from neighboring graves. Union officers ordered that the grave markers be restored along with “suitable head pieces placed over the heads of our men…”46 It may be noted that today the Union Church Cemetery contains a number of tall stately cedar trees perhaps similar to those “noble cedars” described by John Washington.

Additional interments in the cemetery would occur until Union forces vacated the area at the end of August, 1862. They returned again on November 17, 1862, preceding the Battle of Fredericksburg, and camped in Stafford County for the winter of 1862-63. Falmouth was occupied until June 15, 1863, during which time the Union Church Cemetery continued to serve as a burying ground for soldiers who died from wounds and illnesses.

During this second occupation, the Union Church was also utilized as a troop barracks. Oral tradition relates that during the winter: “The interior of the church was entirely destroyed by the Federals. The pews were all chopped to pieces and taken down and practically all the woodwork was cut up.”47 In addition oral accounts suggest the church was used again as a hospital during this time; however, no evidence of a primary source was found. Two primary sources support the use of Union Church as a barracks, but given the vast number of wounded and convalescing soldiers it can be assumed these were also quartered in the church, giving some credence to the belief that the church continued to be used as a hospital.

The United States Christian Commission was operating in Falmouth during that same time and an excerpt from one of its reports follows:

An old tobacco warehouse on the very banks of the river, within hail of the rebel pickets, was cleared of rubbish, the broken ceiling and windows were covered with old canvas, and a small table, borrowed from a neighboring cottage, served as a pulpit. Here, on Sabbath afternoons and on each evening of the week, meetings were held which were largely attended…The village itself was a ruin: its church used as a barracks for troops; its stores and factories closed. A large number of the inhabitants were still there, living as best they could…old men, women, and children. The [delegation’s] station agent …organized a Sabbath school for children, which came to be held every day in the week. Thirty or forty little rebels were gathered in…48

Because the Union Church was the only church in Falmouth, this is the building referred to as “its church used as a barracks” and the account further indicates the lack of an available sanctuary resulting in the use of a tobacco warehouse for religious meetings. The 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry performed provost guard duty in Falmouth and noted in its regimental history “an old grist mill was used…sometimes for prayer meetings…” with no mention of a church building.49

The diary of a member of the 7th Michigan Volunteer Infantry relates that after the Battle of Fredericksburg, “Our regiment is in a deserted village called Falmouth” and three companies of the regiment “are quartered in an old church building. Here we do picket.”50 The 7th Michigan was one of three regiments that crossed the Rappahannock River on pontoon boats on December 11th, 1862, and engaged Confederate troops holding the city of Fredericksburg. This diarist also wrote that, following the Battle of Fredericksburg, a great religious revival broke out among the troops; however, no mention of a church building being used for services may suggest that Union Church was used only as a barracks at that time.

Prior to the Battle of Chancellorsville the Union army moved up river to outflank Confederate forces as part of the strategy for the ensuing engagement. Quartered in the church, Company B of the 7th Michigan Infantry was left behind to continue its picket duty along the river. Pickets discovered a secret telegraph wire submerged in the Rappahannock River and operated from the nearby Conway House, reporting movements of Union troops.51 After the Battle of Chancellorsville the Union Church continued as a barracks until mid-June when the army moved north, following General Lee into Pennsylvania and participated in the Battle of Gettysburg.

Another member of the 7th Michigan Infantry left his name carved into the plaster on the interior wall of the balcony section of the church.52 The interior of the belfry reportedly contains carvings in its wooden framing that were left behind by soldiers. It is probable that Companies B, C, and I of the 7th Michigan Infantry were responsible for destroying the interior woodwork of the Union Church for firewood.

It is possible the Union Church came under artillery fire; however, it cannot be determined by whom or at what instance. On a few occasions either side may have temporarily fired upon the village of Falmouth. A fragment of a three-inch diameter ten-pound Parrott-type artillery shell was found twenty-nine yards from the southwest façade corner of Union Church.53 Since the church is situated on a prominence the shell may have targeted troops congregated there and exploded nearby. Union artillery batteries were positioned on heights overlooking the Union Church during the Fredericksburg Campaign. The site could possibly contain Civil War artifacts including those associated with a hospital. Oral history relates numerous such artifacts were found in 1958-1959 by local relic hunters.54

Just below the Union Church Cemetery hill was the camp of the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry in which one member kept a diary mentioning a visit to the cemetery. An entry for January 9, 1863, records the inscriptions of several grave markers which he found of interest.55 These same markers are present today. Local lore suggests some markers were used for target practice by Union troops with the bullets later dug out with pocket knives for souvenirs.56

During General Grant’s Overland Campaign of 1864, the Fredericksburg area was filled with wounded soldiers. As a prominent building not in use, Union Church was likely occupied again in some capacity during that time, given the massive number of casualties sustained at the battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House.

- Hening’s Statutes at Large, February 1727, Chap. XIV, pp.234-239. Falmouth was previously known as “The Falls Landing”. ↩︎

- Ibid, March 1623-24, pp. 122-123. Falmouth became part of Stafford County in 1776. ↩︎

- Ibid, May 5th and 6th, 1732, pp. 367-369. ↩︎

- Smith, Margaret L. “1720 Falmouth, Va.” ↩︎

- “Virginia Herald” August 14, 1819. Page 3 col. 3. ↩︎

- Brydon, G. MacLaren. A Sketch of the Colonial History St. Paul’s, Hanover, & Brunswick Parishes King George County, VA. 1916. Library of Virginia, 1 vol. 136 leaves typescript (accession number 19756) page 32. ↩︎

- This wrought iron fencing has been repaired with modern weld seams ↩︎

- Oral interview and site visit in 2007 with Mr. Herbert Brooks, Cemetery Trustee ↩︎

- Washington, John. “Memories of the Past”, Chapter 8, p. 21. See also Blight, David W. A Slave No More, Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation . 2007, pp. 195-196. ↩︎

- General McDowell commanded a secondary supporting force occupying Falmouth April 18, 1862 through August, 1862 while General McClellan conducted his Peninsular Campaign as the main drive before Richmond. General Lee’s victory at the Battle of Second Manassas, August 29-30, 1862, resulted in Union forces withdrawing from Falmouth. ↩︎

- “Falmouth was subjected to direct occupation by Union forces for about one quarter of the duration of the Civil War, and for about 80 percent of the middle period of the conflict from April 1862 to June 1863.” Dr. Kerri S. Barile, Dovetail Cultural Resources Group LLC communicated this information in 2008. ↩︎

- A record of the 24 soldiers identified is in Conway House Collections, Union Church File. This research was conducted in 2002 by Norman Schools with assistance from a historian with the National Park Service, Ms. Elsa Lohman, from Chatham. ↩︎

- United States Quartermaster General’s Office. Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defense of the American Union, Interred in the National Cemeteries, No. XXV. 1870. ↩︎

- Official Records . 1881-1902. XXIV p. 53. “Special Orders No. 65 Headquarters Department of the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg, Va. May 13, 1862”. ↩︎

- Information obtained in 2007 from Willie G. Shelton, Jr., cemetery trustee. ↩︎

- Oral interview in 2002 with Mr. Elliot Berry; an aged Falmouth resident now deceased. ↩︎

- Oral interview and site visit in 2007 with Mr. Herbert Brooks, Cemetery Trustee. The ravine was originally an early roadbed which ran down to the Falmouth Ferry, long disappeared. Remnants of this road’s embankment can be seen along one side and behind the parking lot of present Falmouth Baptist Church. This road from its opposite end turned out of Forbes Street to run down to the river. Remnants were pointed out by Mr. Brooks stating the road was abandoned long ago due to the steep terrain. The road was named Old Telegraph Road which name Forbes Street was also known as it ran north out of Falmouth. ↩︎

- On the breech of this artillery piece is stamped: U.S. Rapid Fire Gun Powder Co., Derby, Conn. Model 1908. U.S.R.F.G.&P.Co. 3 Po S.A. MOUNT MARKX No. 591 FHC WT 600 LBS; on the breech block: 3 Pdr. BR.MECH MK.XI GUN NO. 591. There are additional stampings on the breech and a side plate. The artillery piece is painted black. ↩︎

- Smith, Margaret L. “1720 Falmouth Va.” ↩︎

- Louis Berger Group, “Falmouth Historic District Nomination”, 2006, Section 8, p. 31. ↩︎

- Smith, Margaret L. “1727 Falmouth Va.”. The Carter Family investors in Falmouth included: Robert “King” Carter, Robert Carter Jr., John Carter, Landon Carter, and son-in-law Col. Mann Page. ↩︎

- Hening’s Statutes at Large, February 1752, pp. 282-283. ↩︎

- Hening’s Statutes at Large, February 1752, p. 282 ↩︎

- The 1755-60 dates are from the “Brydon Letter” dated September 3, 1948. Brydon was the Historiographer of the Diocese of Virginia and on page 2 of A Sketch of the Colonial History Of Saint Paul’s, Hanover, and Brunswick Parishes, King George County, Virginia 1916 , he states “The Vestry Books and Registers of all three parishes are lost…” further stating “a gleaning of the facts wherever they could be found…has made possible the putting together of at least an outline of the history of each Parish.” For the location of the second brick church Brydon states in the same work, “This second Church stood until shortly after the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was destroyed, and a union Church built upon the foundation of the old walls” page 32. For the location of the wooden church see endnotes 5 and 6. 37 “…two persons, one in Hanover Parish and one in Brunswick Parish, were presented by the Grand Jury in 1737 for not attending church services for one month, and were fined five shillings each. Ten years later, in 1747, the Grand Jury presented five or six persons in Brunswick Parish for non-attendance…” information from: Brydon, George MacLaren D.D. Virginia’s Mother Church . 1947, p.173, footnote no.12. ↩︎

- “…two persons, one in Hanover Parish and one in Brunswick Parish, were presented by the Grand Jury in 1737 for not attending church services for one month, and were fined five shillings each. Ten years later, in 1747, the Grand Jury presented five or six persons in Brunswick Parish for non-attendance…” information from: Brydon, George MacLaren D.D. Virginia’s Mother Church . 1947, p.173, footnote no.12. ↩︎

- Heyrman, Christine Leigh . “The Church of England in Early America”. National Humanities Center. ↩︎

- Brydon, George MacLaren D.D. Virginia’s Mother Church, 1607-1727 . 1947, p.403. ↩︎

- Brydon, George MacLaren, D.D. Virginia’s Mother Church Volume II, p.396. ↩︎

- Conner, Albert Z. A History of Our Own: Stafford County, Virginia . 2003, p.102. ↩︎

- Louis Berger Group, “Falmouth Historic District Nomination”. 2006, Section 8, p. 32. This nomination noted as a draft nomination subject to approval by DHR and intended to replace the original NR nomination for the district. Also see: Rice, Howard C. Jr. and Brown, Anne S.K., editors. The American Campaigns of Rochambeau’s Army, 1780, 1781, 1782, 1783 . 1972. The reference to a Protestant church may indicate the communities re-use of the structure as by this time the Anglican Church of England had fallen out of favor and many parson having returned to England. ↩︎

- Described by Joseph Scott, compiler of “The United States Gazetteer”. See Louis Berger Group. “Falmouth Historic District Nomination”. 2006, Section 8, p. 33. This nomination noted as a draft nomination subject to approval by DHR and intended to replace the original NR nomination for the district. ↩︎

- Brydon, G. MacLaren letter dated September 3, 1948. A Copy is in the Conway House Collections, Union Church files. ↩︎

- Library of Congress, “Religion and the American Revolution”. Brydon states in his Virginia’s Mother Church , Volume II, p. 28: “Under the act of incorporation adopted by the General Assembly in December 1784, the first annual convention of The Protestant Episcopal Church of Virginia assembled in May 1785, adopted its first code of canon laws, and elected clerical and lay deputies to a meeting of similar deputies from other States which had been called to form a general convention.” He also states the year for burning as 1818 in his “Brydon Letter” dated September 3, 1948. ↩︎

- “Virginia Herald” August 14, 1819, page 3 col. 3. ↩︎

- The beaded purse depicting the Union Church and the French flag was probably made as an accessory for attending a ball given in honor of Lafayette’s visit. This beaded purse is in the Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center Collections, Fredericksburg, VA. ↩︎

- Described by gazetteerist Joseph Martin. See Louis Berger Group. “Falmouth Historic District Nomination”. Section 8, p. 36. This nomination noted as a draft nomination subject to approval by DHR and intended to replace the original NR nomination for the district. ↩︎

- Crane, Lydia. “Falmouth A Virginia Village in the ‘Forties’ from a Child’s Point of View”. Free Lance, March 15, 1898. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel. Autobiography, Memories and Experiences . 1904. Vol. I, pp. 42, 43 and 102. ↩︎

- Conway, Moncure Daniel. Autobiography, Memories and Experiences . 1904. Vol. I, pp. 27-28. ↩︎

- Correspondent. “Janesville Gazette” Wisconsin, April 28, 1862 “H. Q. Seventh Regt. Wis. Vol. Camp No. 11 near Fredericksburg, Va.” ↩︎

- Crane, Lydia. “Falmouth A Virginia Village in the ‘Forties’ from a Child’s Point of View”. Free Lance, March 15, 1898. ↩︎

- Washington, John. “Memories of the Past”. Chapter 8, p. 21. See also Blight, David W. A Slave No More, Two Men Who Escaped to Freedom Including Their Own Narratives of Emancipation . 2007, pp. 195-196. ↩︎

- Letter dated April 22, 1862 from Falmouth and written by Lt. Charles Morton, 2nd New York Cavalry. The other regiment of cavalry was the 1st Pa., this and the 14th New York Infantry participated in the advance on Falmouth. ↩︎

- The original cart de visite image of Lt. Decker is in the Conway House Collections. An account of Decker’s death states: “Lieut. Decker from Orange Co.[Conn.], was gallantly leading his men, and coming up alongside of a rebel officer, made a cut at him, when he turned and shot him with his revolver through the heart. He fell and his horse followed the rebels.” The account is from a letter dated April 20, 1862 by another officer, Lt. Charles Morton, of the same regiment. The names of the other cavalrymen killed are as follows: Patrick Devlin, Co. M, 1st Pa.; Thomas Norton, Co. M, 1st Pa. Cal.; Michael Rudy, Co. M, 1st. Pa.; John Heslin, Co. L, 2nd N.Y.; Josiah Kiff, Co. H, 2nd N.Y.; and George Weller, Co. H, 2nd N.Y. ↩︎

- White, Wyman S. The Civil War Diary of Wyman S. White 2nd United States Sharpshooters , 1993, p. 59. ↩︎

- Official Records. 1881-1902, XXIV p. 53. “Special Orders No. 65 Headquarters Department of the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg, Va. May 13, 1862”. ↩︎

- Louis Berger Group. “Falmouth Historic District Nomination”. 2006, Section 8, p. 43. This nomination noted as a draft nomination subject to approval by DHR and intended to replace the original NR nomination for the district. Also see WPA report 1934. ↩︎

- Moss, Lemuel. Annals of the United States Christian Commission . Philadelphia 1868. pp. 377-378. ↩︎

- Bruce. The Twentieth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865 . 1906. p.228. ↩︎

- Rice, Melvin. Company B, 7th Michigan Vol. Inf. Copies of 1902 transcripts from his Civil War diary, privately owned. A copy is in the Conway House Collections. ↩︎

- Newspaper articles, “Philadelphia Inquirer” April 24, 1863 and “Boston Traveler” April 27, 1863, p. 2, col. 5. See also Official Records: Vol. XXV part 2, pp. 269-270, “Headquarters Army of the Potomac April 27, 1863” Joseph Hooker to Hon. E.M. Stanton, Secretary of War and Vol. XXV part 2, pp. 300-301, “Washington D.C. April 30, 1863-1:10 pm” Edwin M. Stanton to Major-General Hooker, Falmouth, Va. ↩︎

- “7 M Edward Wise Co. I” Edward Wise was in Company I, 7th Michigan Volunteer Infantry. Wise survived the war but returned to Michigan and hung himself in a barn. See photograph of the carvings included in extra photographs. ↩︎

- This shell fragment with its documentation is in the Conway House Collections. ↩︎

- Oral interview in 2008 with Mr. Charles Michael Shelton, a relic hunter and Falmouth resident at the time. This relic hunting activity probably correlated to some type of grading and debris clean up of the grounds behind the narthex. ↩︎

- Taylor, Isaac Lyman. Campaigning with the First Minnesota, A Civil War Diary . 1944, p. 241. See his entry for “Fri. January 9”. ↩︎

- Related in 2008 by Billy Shelton, Cemetery Trustee. ↩︎