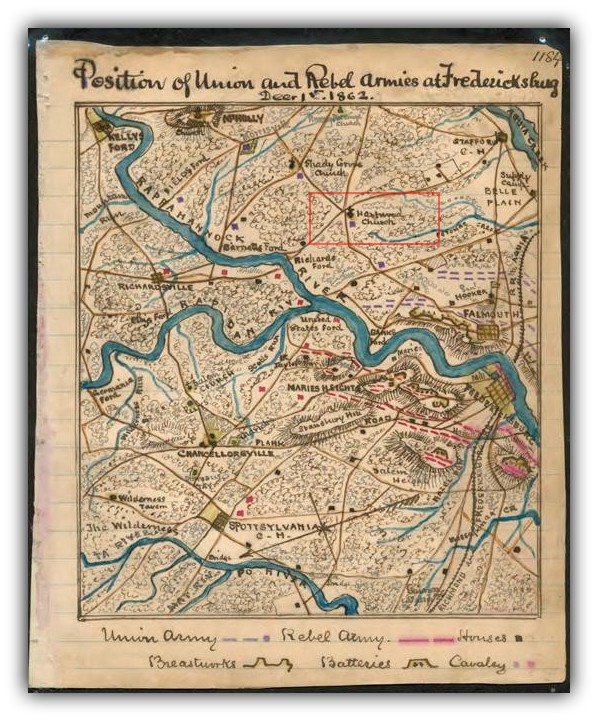

As usual when we decide to gallivant into the Virginia countryside, we first consult with the National Register of Historic Places, and guess what we found. We found an historic church that was significantly impacted by the Civil War. After a general historical background, we will cover the November 28, 1862 Wade Hampton’s operation when he captured 137 men of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry. After much research we found two fascinating newspaper reports from the field. One on December 1, and the other on December 2. We transcribed both from original copies and they are recorded below. Following we will continue to record how the impact of the Civil War did not end on November 28, 1862.

The History of Hartwood Presbyterian Church

The Church of England was legally established in the colony in 1619. In practice, establishment meant that local taxes were funneled through the local parish to handle the needs of local government, such as roads and poor relief, in addition to the salary of the minister. After independence from Britain the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom was passed in the Commonwealth granting Virginians religious freedom and the chance to worship as one chose. Originally in Hartwood, Anglican worshippers attended what was known as the “Chapel of Ease” of Brunswick Parish called Hartwood Chapel. History also has reference to the Yellow Chapel which apparently also existing on this site or was another name for Hartwood Chapel. The old church was definitely Presbyterian by 1807, and the Winchester Presbytery officially organized the Hartwood/Yellow Chapel Church on June 2, 1825. The Presbyterians eventually built a brick church nearby the original site, circa 1858. There is a small depression, about twenty by thirty feet, located about sixty feet west of the present church and is believed to be the probable site of the Hartwood/Yellow Chapel structure. During the Civil War, Hartwood Presbyterian Church was a point of contention between the two sides.

Hartwood Presbyterian Church was the specific site of Wade Hampton’s November 1862 capture of 137 men of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, most of whom were asleep inside the church building. This action was the first of two cavalry incidents which befell Hartwood Presbyterian Church. According to Dr. Douglas Southall Freeman, “It was the first independent operation in Virginia undertaken exclusively by cavalry from states farther south. The men and the leader (Wade Hampton) won high praise for this raid, (but it) started an angry hue-and-cry among the Federals.”1 The Union officer in charge, Captain George Johnson of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, on the other hand was dishonorably discharged for “negligence and disregard for orders” in connection with the capture. The church was location of five skirmishes in the fall of 1863.2 We will get to what is known about these additional actions at the church later.

The Movements of General Ambrose Burnside Toward Fredericksburg with Hartwood Church in His Path

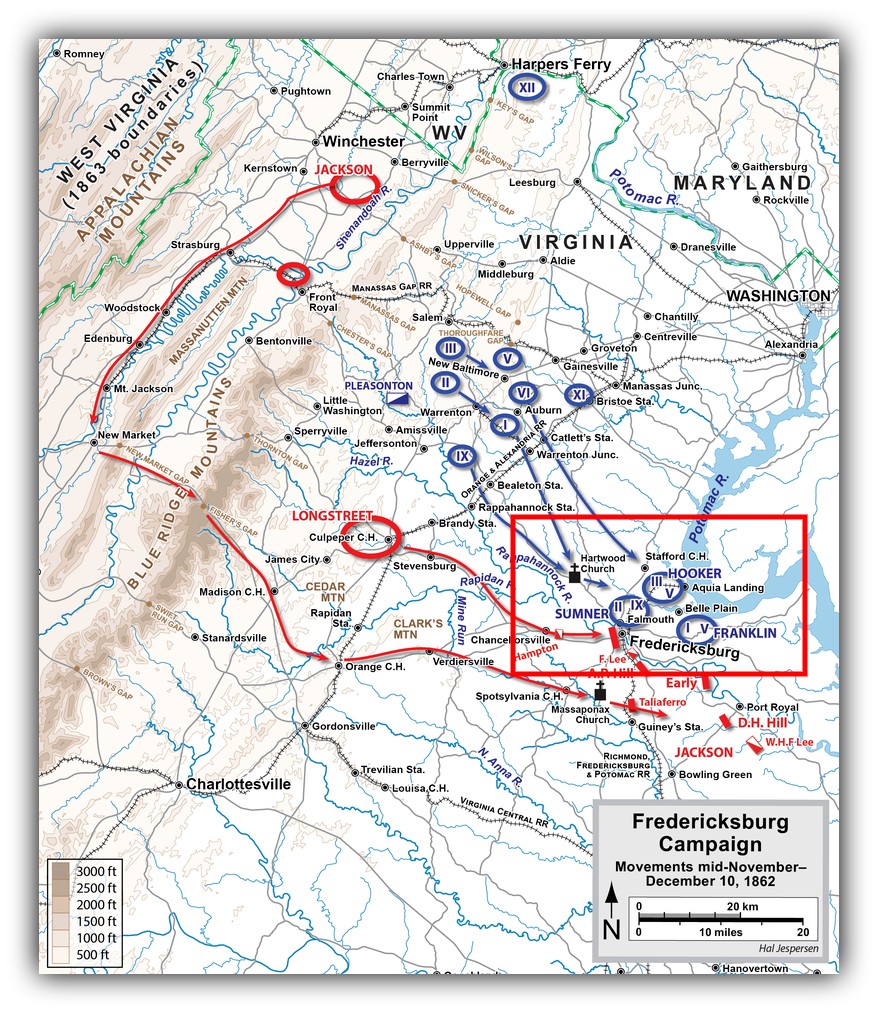

Leaving the Warrenton area on November 15, Burnside moved his 100,000-man army 35 miles to Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock in just two days. This movement was to weigh heavily on the residents of Hartwood and Hartwood Church. Situated at the intersection of so many important roads on the pathway to Falmouth and Fredericksburg this area could not escape occupation by the masses of Federal troops.

Many of the local residents were greatly burdened by the occupying Union forces. One of them was Robert Rogers, a merchant and postmaster, who also was the owner of “Hartwood Plantation” located near the church. According to one post-war affidavit, Rogers in the early years of the war had 100 acres of his property divided into five fields. When Burnside’s army moved through the area in November 1862, the Union Soldiers not only “used up the whole” of Rogers’ wood-rail fencing for fuel but also took his “livestock and property in the amount of $2210.” His claim for reimbursement was never paid.3

Another instance of the occupation’s impact was the house of William and Sinah Irving whose house was commandeered by the Federal garrison for use as an officers’ quarters. The family was forced to abandon the first floor of their home, recently furnished with a new piano and new rugs, the Irvine’s household, including their son, daughter, and two young friends, were relegated to the second floor. Unable to secure their possessions, the family later reported that when the Federals withdrew, the downstairs rooms, including the new furnishings, had to be cleaned out with shovels.4

The Situation Facing the Confederate Cavalry

The rapid movement by Burnside caught General Lee unaware. Lee, because of this, needed to engage every resource he had to counter this movement. On November 10, 1862, after assessing the situation of his cavalry forces, General Lee conveyed his concerns in two letters. In the first to Secretary of War George W. Randolph, Lee wrote, ” the diminution of our cavalry causes me the greatest uneasiness. General Stuart reports that about three-fourths of his horses are afflicted with sore tongue, but a more alarming disease has broken out among them, which attacks the foot, causing lameness….. Unless some means can be devised of recruiting the cavalry, I fear that by spring it will be inadequate for the service of the army. Horses are so scarce and dear that the dismounted men are unable to purchase them.”5

In the second letter, this one to Major General Gustavus W. Smith, Lee sounded the alarm even more dramatically. “The diminution of our cavalry from a disease among the horses is lamentable. I learned today that the colonel of the Ninth Virginia Cavalry reported only 90 effective men for duty. While the pressure of service is so great upon the cavalry, I see no means of recruiting it.”

With Union General Ambrose Burnside suddenly making a move on Fredericksburg on November 15, Lee needed to address this issue regarding the use of his cavalry. After this sudden and undetected movement by Burnside, Lee came to the conclusion that he needed to increase the army’s surveillance capabilities to prevent this from happening again. His solution was to develop a group of small detachments of scouts behind enemy lines. It fell to two brigade commanders, Brigadier General Wade Hampton and Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee.

This was Hampton’s mission since his arrival in the vicinity of Fredericksburg. Hampton’s brigade had been on picket near the confluence of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers above the city. For his mission, Hampton chose 50 troopers from the 1st North Carolina Cavalry and the Cobb Legion, 40 troopers from the Lieutenant-Colonel Martin’s Jeff Davis Legion and 34 troopers from the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry and Colonel William Phillips’ Georgia Legion. These were the troops that would infiltrate Union lines and arrive undetected at Hartwood Presbyterian Church on November 28.

The narrative below by Wade Hampton describes the nature of his men. He mentions their dedication and how they lived constantly within the lines of the enemy. The newspaper article, from the Philadelphia Inquirer below this, confirms this is how these men were able to work hand in hand with the citizens of Hartwood to bring about the capture of these two squadrons. Both the transcribed newspaper articles give details of the events of November 28.

Lieutenant General Wade Hampton, from the Connected Narrative of Wade Hampton III, Hampton Family Papers, South Carolina Library, University of South Carolina.

Mention having been made in my Report of the good conduct of my scouts, it is proper & just that in a narrative of the operations of the cavalry some acknowledgement should be made of the services of these men, who were so zealous, so bold & so intelligent. The mere record of their services would swell this paper to too great a size & to give even the names would occupy too much space, but I desire to declare that they were of incalculable use to me & that they were in general earnest, active & devoted. Living constantly within the lines of the enemy, no movement escaped their observations & I was kept regularly appraised not only of the position, but of the strength, organization, & often even the very purposes of the enemy. Nor were their operations confined solely to the collection of information for they were constantly engaged in active hostilities & several most brilliant affairs were conducted by them.

Two Squadrons Third Pennsylvania Cavalry Captured. Special Correspondence of the Inquirer. Falmouth, Va., November 29, 1862:

About daylight yesterday morning the first and third squadrons of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, belonging to General Averell’s Cavalry Brigade, while doing picket duty near the Hartwood Church, about twelve or fifteen miles from here, on the Warrenton road, were suddenly attacked by a very heavy force of Rebel cavalry, and, after a brief resistance, against overwhelming odds, were finally captured.

This unfortunate occurrence, and other of a like nature, are to be expected in a country like this, where every resident, male and female, are spies upon our actions, and take every occasion to injure us. There are a number of citizens, notorious in their rebel sympathies, residing in the neighborhood, who have free access in and about our lines. In fact, these men have more freedom than our soldiers. I have always been of the opinion that these are war times, and that we are here for the protection of those who, at any moment, would destroy us.

There is no doubt that the rebels who surprised the above cavalry force, were apprised how they were posted before the attack, hence their success. All attacks of this kind are made just at the dawn of day – the sleepiest part of the hour of rest – the time when men sleep the soundest.

The rebels came through the woods in a round about way, attacking the reserve pickets, without disturbing in the least the advance line. They came in the rear, a point that was deemed entirely safe, charging with their usual shouting and rapid firing.

The following companies compose the two squadrons that were captured: – Companies C and F, under the command of Captain Johnson, of Company F, Lieutenant Warren commanded company C, The Third Squadron, Companies G and M, under command of Captain Hess, of Company M. Lieut. Englebert commanded Company G. Lieutenant Heyt, of Company M, was also captured. This makes five commissioned officers and at least one hundred men. Some twenty-five men escaped, with the loss of their arms.

Captain Jones, of Company C, is acting Lieutenant Colonel, and was not out with his company, he thus escaping capture. Wes Fisher, a private of Company C, escaped, being chased for over five miles by a score of Rebel cavalry, who fired at least forty shots at him, two of them going through his clothes. This man drew his sabre, when his ammunition gave out, stopping the leading Rebel, who was not inclined to have a hand-to-hand fight. As far as we can ascertain, there are four men wounded and nine killed. The following are their names:

Adam Heigle, bugler, Company F, shot in the abdomen, not badly. This man was shot after he had surrendered, the Rebel who shot him not being over five yards off. Sergeant Morris, Company G; Michael McCullough, Company G, and Ed. Arthurs, of Company M.

Captain W. J. Gary, commanding another squadron of the same regiment, consisting of companies D and E, were also on picket, and as soon as he heard of the surprise, extended his pickets, and sent to Stafford Court House for reinforcements.

The surprise on the part of the rebels was a complete success to them. After getting possession of the camp and appendages, they, the Rebels, retired by various roads, scattering over the country, for the purpose of eluding our troops who went out to make a recapture, if possible. The wily enemy escaped to Warrenton. The Third Pennsylvania Cavalry is a first-class regiment, and the disgrace of this surprise will fall heavy on the officers by whose neglect it was committed.

Aquia Creek. November 29 – Yesterday morning, about daylight, two squadrons of the 3d Pennsylvania Cavalry, doing picket duty in the neighborhood of Hartwood Church, some fifteen miles from Falmouth, on the Warrenton road, were completely surprised by a large body of rebel cavalry, who got in their rear by a circuitous road, and no doubt piloted by a resident of that vicinity.

The two squadrons consisted of four companies, under command of Captain Johnson, of company F. Captain Hess commanded the Squadrons. Companies C, F, G and M were captured, consisting of at least one hundred men and five commissioned officers. Captain E. Jones, of company C, is the acting lieutenant colonel of the regiment, and thus was not with his company, and escaped capture. Lieut. Englebert commanded company G. Lieut. Heyl also was captured.

Out of the two squadrons about twenty-five escaped, with loss of their equipments. Wesley Fisher, a private of company C, was chased over five miles by a dozen rebels, they firing about forty shots at him, he returning the fire until his ammunition ran out. He then drew his sabre, but the enemy would not follow. Fisher received two balls in his clothes.

Four of our cavalry were wounded – Adam Heigle, bugler company F; Sergeant Morris, Company G; Michael McCulloch, company G; and Edward Arthurs, company M. The surprise, on the part of the rebels, was complete, taking our men at daylight, the sleepiest part of the hours of rest. It was the reserve camp attacked; the outmost pickets not being disturbed. Captain Garry, commanding another squadron, rushed to the scene at the sound of the firing, but the enemy, dividing the prisoners, escaped on different roads, carrying the prisoners away with them.

The First Battle of Fredericksburg

To be clear this operation by Wade Hampton was only one of several actions that impacted Hartwood Presbyterian Church and the greater Hartwood area. Subsequent to this action on November 28, 1862, the Battle of Fredericksburg was to be fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg and therefore Hartwood. The distance between Fredericksburg and Hartwood is less then 10 miles.

With nearly 200,000 combatants—the greatest number of any Civil War engagement—Fredericksburg was one of the largest and deadliest battles of the Civil War. The Union Army of the Potomac suffered more than 12,500 casualties. Lee’s Confederate army counted approximately 6,000 losses.

Leaving the Warrenton area on November 15, Burnside moves his 100,000-man army 35 miles to Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock in just two days. Falmouth is approximately eight miles from Hartwood. Opposite Falmouth is the river port town of Fredericksburg, occupied by only a few hundred Confederates. Located halfway between Richmond and Washington D.C., Fredericksburg has largely escaped the ravages of the war. The bridges across the river there have been destroyed earlier, however, so Burnside orders portable pontoon bridges to be sent forward to his army. Arriving in Falmouth, Burnside discovers that bureaucratic and logistical tie-ups in Washington have delayed the bridges and his carefully devised plan to surprise Lee is in jeopardy.6

The pontoons finally arrived November 25, 1862. In the pre-dawn of December 11, the Union Army finally made its move. Union Engineers would erect five pontoon bridges. Using the darkness and a thick fog as cover, Union engineers began to construct two pontoon bridges which would lead them to the upper town. A third pontoon bridge would lead to the lower end of town about one-half mile down river below the destroyed railroad bridge. Two additional pontoon bridges were erected a mile further down river; there were three crossing sites in total. At the Upper Crossing, the engineers came under fire from Confederate sharpshooters positioned along the riverbank, which prevented the completion of the bridge. A Union bombardment of the town failed to drive out the Confederates. Eventually, Union infantry soldiers were sent across the river in boats to clear out the Confederate sharpshooters. Fighting soon spread through the streets as the Union soldiers pushed the Confederates back. This allowed the engineers to complete the bridges. Union troops moved across the bridges and occupied Fredericksburg on December 12, 1862.

In February 1863, Confederate General Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry led raids in the area of Hartwood Church. The plan was for General “Fitz” Lee to lead troops from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Virginia Cavalry regiments to go behind Union lines. On February 24, 1863, Lee and his troops left Culpeper and crossed the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford. On February 25, they reached the picket lines near Hartwood Presbyterian Church, where they were able to overtake the troops, and then pressed on toward Falmouth. In the area near Berea Church, Union defenses were able to overtake the Confederate Cavalry, which then retreated across the Rappahannock River to Fauquier County.

The Civil War’s impact on Hartwood Presbyterian Church

The immediate impact to Hartwood Presbyterian Church was the damage to the building itself. A good testimony to start with is from Private John W. Haley, 17th Maine Infantry, in a diary entry dated June 11, 1863.

“Myself and another … decided to take shelter at Hartwood Church, a small brick structure. On entering, we were struck with a number of texts and embellishments executed in charcoal on the walls. The seats have been torn out, the windows and doors smashed, and the walls covered with obscene characters and writings. A body of Union Cavalry did this dastardly desecration in the house of worship – a sufficient commentary on the characters of these dirty caricatures of patriots. No matter if it is a Rebel house of worship, its character should be a protection against vandalism. Such treatment of churches is a disgrace to the much-boasted civilization of the nineteenth century.”

The consequences of Captain George Johnson’s “negligence and disregard for orders”.

“After the most careful and most comprehensive instructions and with a timely warning fresh in his memory, Captain Johnson permitted his command to be surprised and a greater portion of it captured, bringing disgrace and shame upon his regiment and the brigade to which it belonged, and our cavalry service into disrepute. I have the honor to request that the name of Capt. George Johnson, Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, be dropped from the rolls, or, if an opportunity shall occur to bring him to trial, that it may be done.” – Gen. William W. Averell, Nov. 29, 1862

- Hartwood Presbyterian Church website Civil War Years. ↩︎

- Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee’s Lieutenants. A Study in Command. Vol. II (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), pp. 398-399; History of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry (Sixtieth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers) in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Philadelphia: Franklin Printing Company, 1905), pp. 172-173; The War of the Rebellion; A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901), p. 407; E. B. Long with Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day Almanac. 1861-1865 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1971), p. 957. Robert K. Krick, Chief Historian, Fredericksburg-Spotsylvania National Military Park, Fredericksburg, Virginia, provided major assistance in research and commentary on the Civil War history of the site and area. ↩︎

- The church on the hill : a history of Hartwood Presbyterian Church – Taylor, George D. (George Douglass), 1905-1996. ↩︎

- The church on the hill : a history of Hartwood Presbyterian Church – Taylor, George D. (George Douglass), 1905-1996. ↩︎

- War of the Rebellion – Chapter XXXI. CORRESPONDENCE, ETC,-CONFEDERATE. ↩︎