Union soldiers at Massaponax Church, May 21, 1864. This view looks west from Telegraph Road. Many of the soldiers who appear in this photograph belong to the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers, a regiment that was then serving as headquarters guard for the Army of the Potomac.

Grant’s Counsel of War, Massaponax Baptist Church, and the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

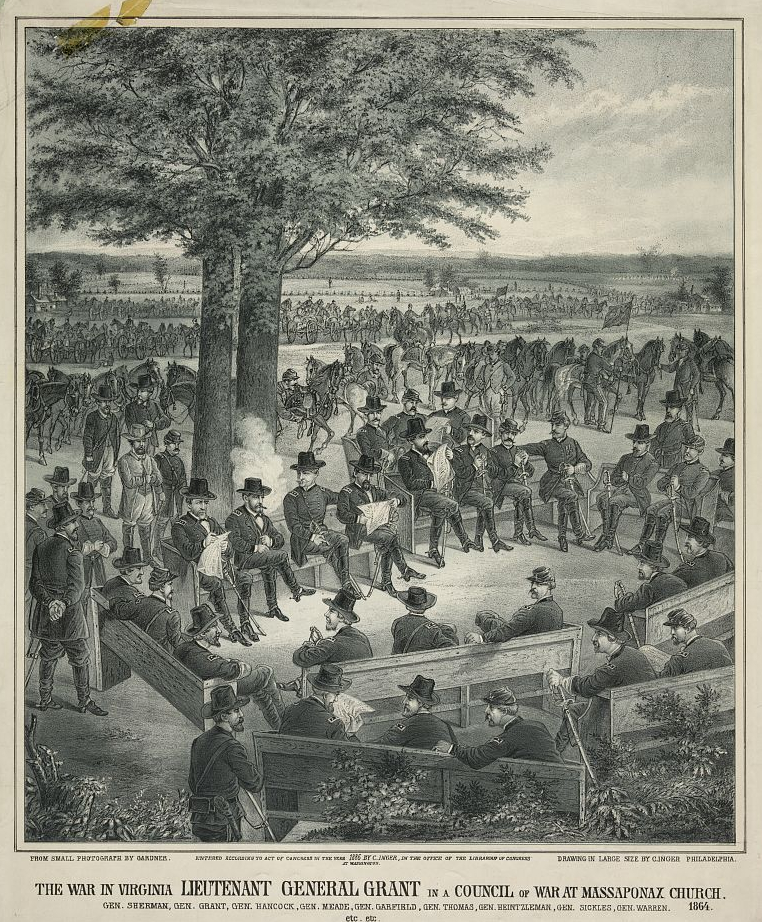

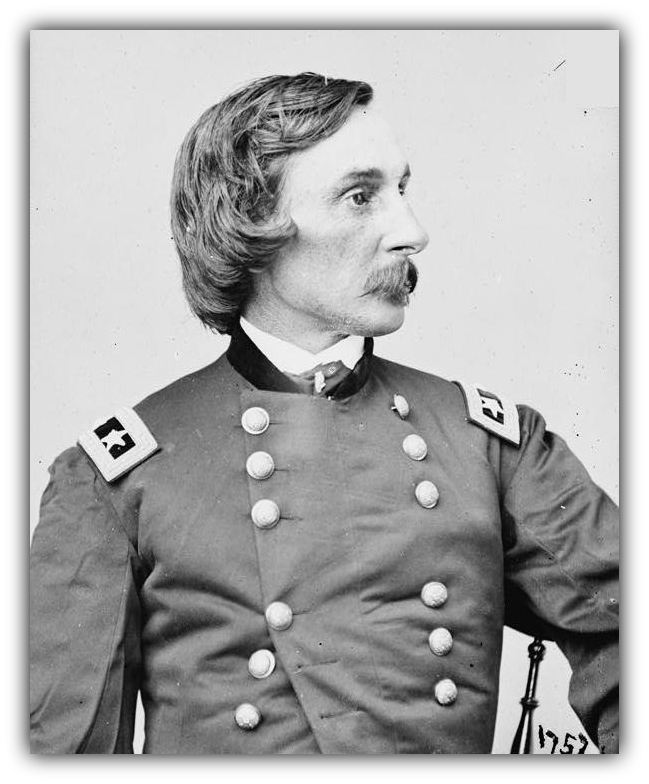

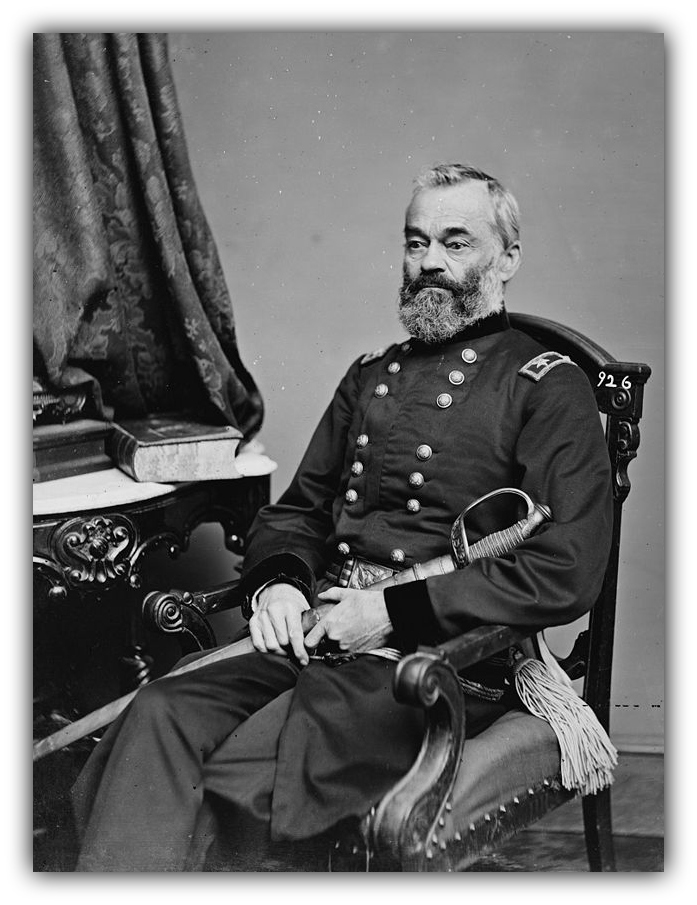

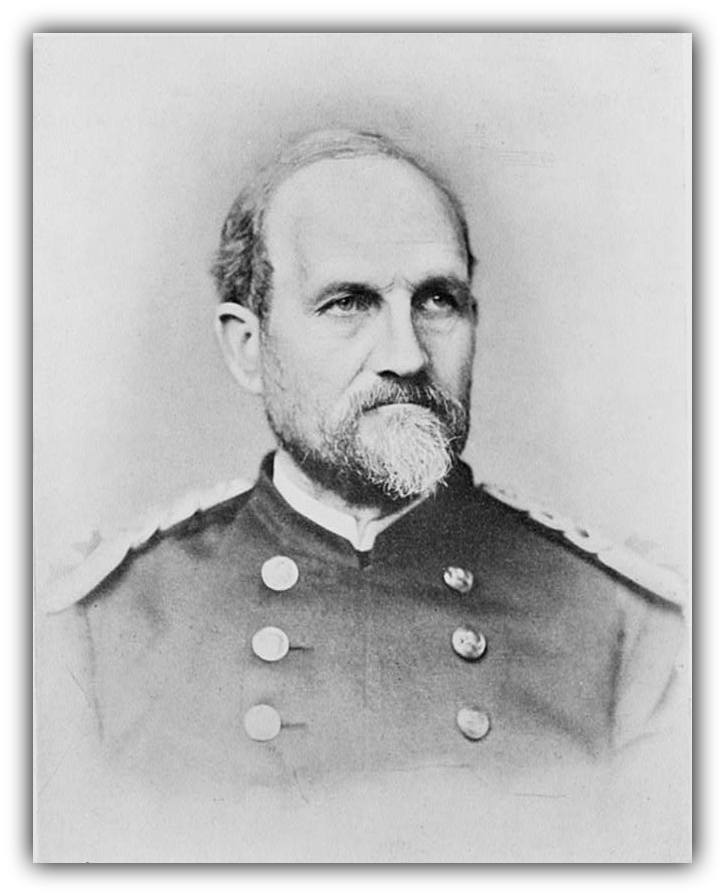

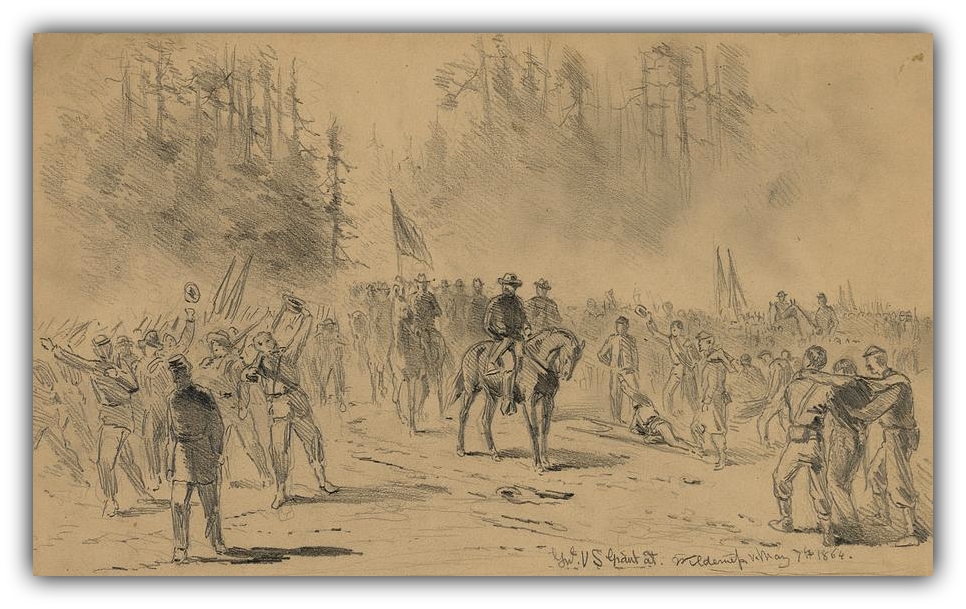

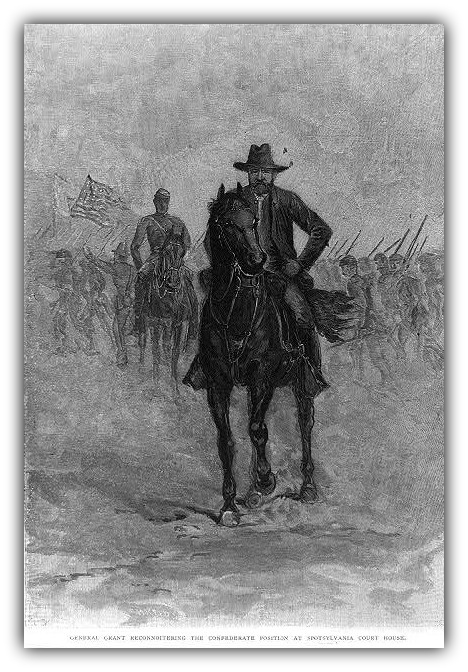

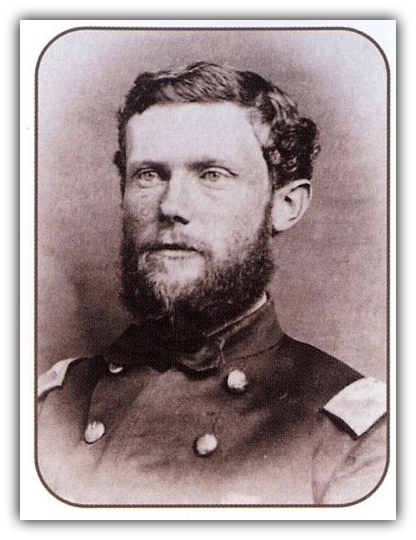

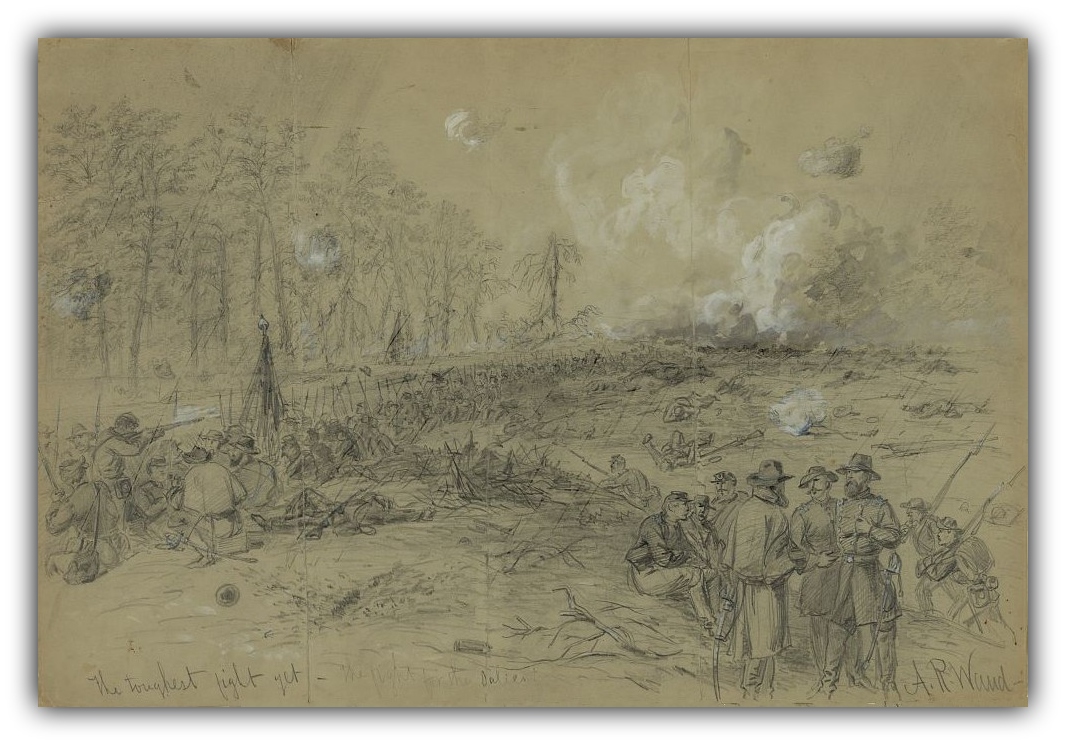

Our trip to Massaponax Baptist Church, Fredericksburg, VA was triggered by it being on the National Register of Historic Places and after reading the descriptive Registration Form. The historic aspect of the Registration Form was Lieutenant General Grant’s Council of War held May 21, 1864. Digging deeper the only information that was connected to it was the on-site photography of Timothy O’Sullivan. The Registration Form clearly states: “Grant, Meade, Dana, and their staffs left no tangible evidence of their conference in the churchyard other than O’Sullivan’s photographs.” The photograph pictured below was created “FROM SMALL PHOTOGRAPH BY GARDNER”. In actuality it was a photograph by Timothy O’Sullivan, who worked for Gardner. The caption is titled “THE WAR IN VIRGINIA LIEUTENANT GENERAL GRANT IN A COUNCIL OF WAR AT MASSAPONAX CHURCH. GEN. SHERMAN, GEN. GRANT, GEN. HANCOCK, GEN. MEADE, GEN. GARFIELD, GEN. HEINZLEMAN, GEN. SICKLES, GEN. WARREN, etc. etc. 1864.

The History of Massaponax Baptist Church – National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Massaponax Baptist Church was constructed in 1859 as the second church to be occupied by a congregation founded in 1788. The first church probably was a log structure located on the banks of Massaponax Creek, about three miles southeast of the present church.

The church constructed in 1859 is a well-preserved example of the Classical Revival style that was popular in antebellum rural churches. It retains many of its original features, including the pews. The church may be more important, however, for its association with the Civil War, and in particular with the use of a twenty-five-year-old invention – photography – during that war.

Documentary photography began to come of age in the United States during the Civil War. Although some photographs exist of American troops in the Mexican War (1846-1848), the Civil War was the first conflict on the continent in which the cumbersome camera, which was far better suited to making portraits, landscapes, and still lifes, was used to convey the sense of combat action to the American public. To accomplish that task the photograph produced by the camera offered a double illusion – an image of reality with the appearance of immediacy – that was not possible with other visual media such as engraving and painting.

In fact, the “action” almost always was posed, and the “event” usually occurred hours, days, or weeks before the photographer exposed his film. Furthermore, the photograph usually was seen as an engraving in Harper’s Weekly or some other newspaper or magazine. The photographer himself was limited in what he could produce by the size and awkwardness of the camera and other paraphernalia, as well as by the slow responsiveness of the wet plates that captured the scenes before him.

Despite the technical problems they confronted, however, the photographers of the Civil War produced a remarkable visual record of that struggle. They wrung the most they could from the technology available to them and overcame many of the constraints imposed by their equipment. One of the most impressive examples of their achievements are a series of photographs taken at Massaponax Baptist Church on 21 May 1864.

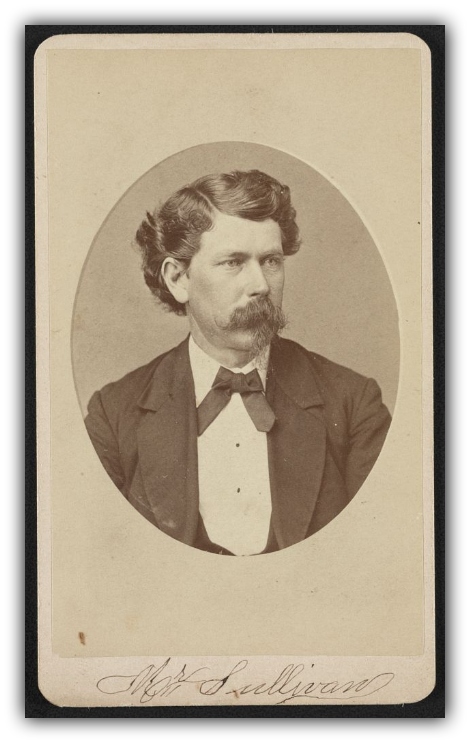

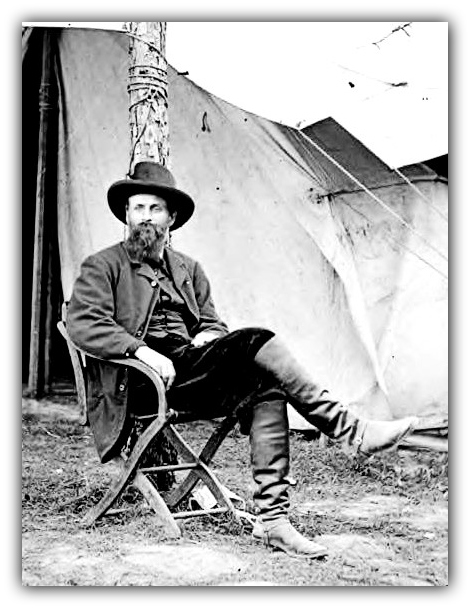

The photographer, Timothy O’Sullivan, is one of the outstanding photographers of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, not only for his record of the Civil War but for his subsequent images of the American West. In May 1864 he was in the employ of Alexander Gardner, another excellent photographer of the period.

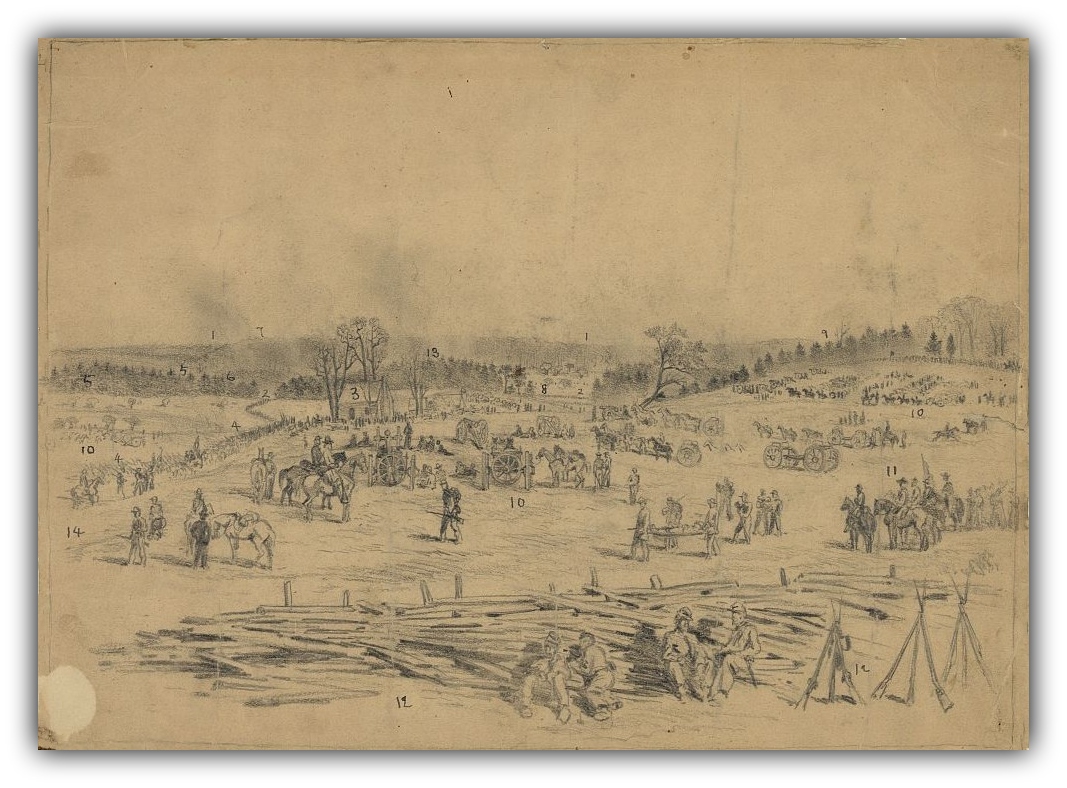

On 21 May 1864 Grant halted his army at Massaponax Baptist Church for a council of war with General George Gordon Meade, the victor at Gettysburg in 1863. Soldiers carried pews from the church and arranged them in a circle in the churchyard. The generals and their staffs met in the pews, where they conferred, studied maps and newspapers, and wrote dispatches. O’Sullivan photographed the church and its yard twice, then hauled his heavy equipment inside the building and climbed the stairs to the balcony. He set up his camera in a window overlooking the churchyard and exposed three plates after he focused on the scene below.

Although the exact sequence of exposure is not clear, O’Sullivan’s photographs show Grant sitting and thinking, leaning over a staff officer’s shoulder to study a map, and scribbling an order. The only order in Grant’s handwriting to be found in Civil War records for that day is datelined “Massaponax Church” and directed to Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside. This order probably is what Grant was writing when O’Sullivan photographed him.

Besides Grant, O’Sullivan’s photographs include images of Meade and Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, who had just returned to the army that morning from a quick visit to Washington. Dana’s presence in the field, his role as liaison between Grant and the national government, and the fact that he is seated next to Grant in one of the photographs, are striking reminders of the tight political control that President Abraham Lincoln exercised over his generals.

Grant, Meade, Dana, and their staffs left no tangible evidence of their conference in the churchyard other than O’Sullivan’s photographs. Several of the private soldiers who either were there that day or were treated at the church when it served as a hospital were not as reticent, however. They scribbled their names, and sometimes their units and opinions, on the walls inside the church. Both physically and in images, then, Massaponax Baptist Church serves as a reminder of the warriors who once stood on its grounds.

THOSE KNOWN IN ATTENDENCE

ALTHOUGH THERE IS NO RECORDED OFFICIAL HISTORY OF THIS COUNCIL, THERE WAS AN URGENCY TO CALL IT

Upon studying the Registration form, the conclusion it reached that Grant, Meade, Dana, and their staffs left no tangible evidence of their conference in the churchyard other than O’Sullivan’s photographs, was perplexing. So, we started digging, and yes, we could no recorded official history of this Council, no dispatches in its regard, and through our research, no mention of it in Grant’s extensive memoirs or the writings of any of those that attended. We did find a newspaper report from the field by someone that was there at the Council giving us his insights. The important question to be answered, however is why it was held, and we will try to make that clear from the writings of Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, Aid-de-Camp to General Grant, in his book Campaigning with Grant.

Following this will be an overview of the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House mainly recorded from the field by newspaper reporters. Spotsylvania was the second major battle in Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant and Major General George G. Meade’s 1864 Overland Campaign. This was following the bloody but inconclusive Battle of the Wilderness. Fighting at Spotsylvania, occurred on and off from May 8 through May 21, 1864, as Grant tried various strategies to break the Confederate line. In the end, the battle was tactically inconclusive. Understanding this battle and the importance of it in Grant’s tactics to reach Richmond, the inconclusiveness of its outcome, and Grant’s understanding from the field that General Sigel had been badly defeated at New Market and was in retreat; General Butler had been driven from Drewry’s Bluff, though he still held possession of the road to Petersburg; and that General Nathaniel Banks had suffered defeat in Louisiana, was pivotal in Grant’s decision to call the Council. We will start off with a newspaper report from the field. This will be followed by Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter, Aid-de-Camp to General Grant’s assessment of Grant’s determination to stay the course.

A first-hand account conveyed to The Pittsburgh Commercial by letter from the Reverand Herrick Johnson. Published Monday, June 06, 1864 · Page 2

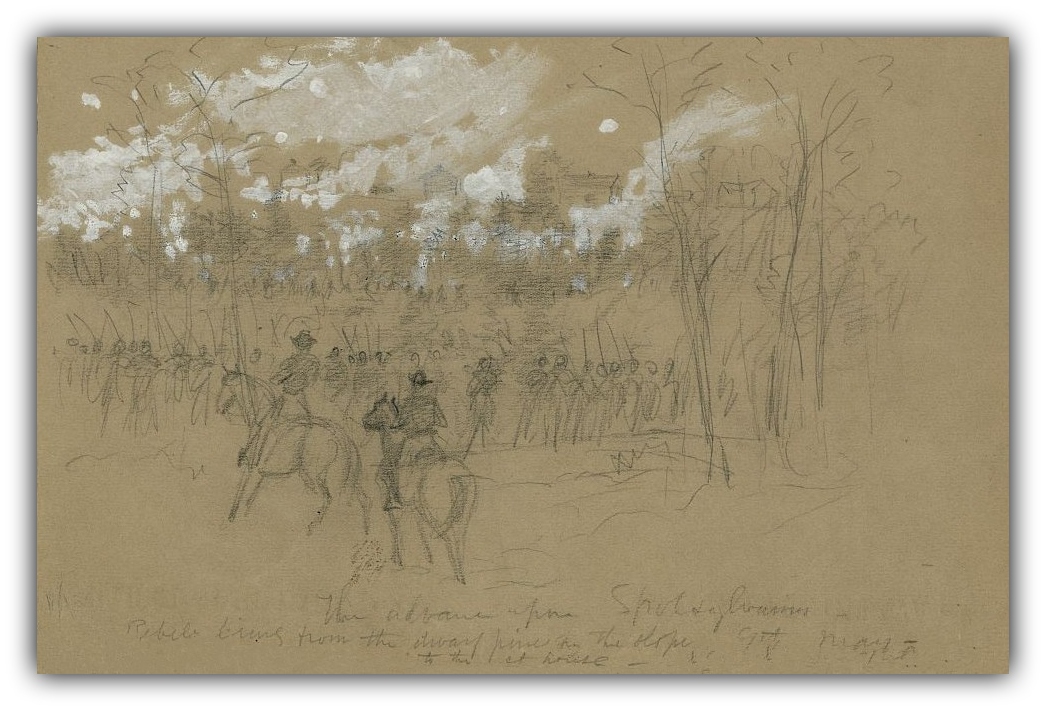

Writing of the movement of Hancock’s Corps at night on May 20, 1864: “The advance of Hancock’s Corps was already far to the left, on the great flank movement to the North Anna. The rumbling of the wheels of artillery and army wagons was the music with which we lay down our sleep under the still stars. The next day the whole army swung around to the left. On they went, tens of thousands upon tens of thousands, in one vast stream, far to the right of the road, far to the left of it, on either side of it, and in it, cavalry, artillery, infantry, army wagons and ambulances, in the midst of all the apparent confusion and chaos and wide separation of forces held well in hand by the ordering genius of the Commander-in-Chief. The man that moves the Army of the Potomac as Ulysses S. Grant does, must have pluck and dash and daring not only, but brains.

A halt was ordered at Massaponax Church, to await tidings from Hancock. And here a fine opportunity was afforded to look into the faces of the men who seem to be the instruments, under God, of determining grand issues in this crisis-hour of the nation. Grant, Meade, Adjutant General Williams, Assistant Secretary of War Dana, and lesser lights constituted the group. Not three minutes after they were seated, chancing to look toward the church, a characteristic scene presented itself. There in the gallery at the front window was “our own artist,” this time literally “on the spot,” with his camera leveled at the starred shoulders, “taking a picture.” (Timothy O’Sullivan)

The mail was just in from the base, and Grant was reading a letter. His is not a presence that would command attention on the instant. He has no prominent striking feature. But look more closely. See the knit of the facial muscle. What a quiet determination settles there in the eye. How all the lines of the face speak of firmness. The lip tells you of dash and daring – the eye of resolution – the whole countenance of tenacity. You see the spirit that resolutely kept the army facing toward Richmond after that two day’s awful havoc in the Wilderness.

He finished his letter and stepped to the side of Meade, who, with a member of his staff, was studying a map. Meade is a larger man than the Lieutenant General, with more marked features. His spectacles rest well on that large prominent nose. His head indicates breadth, comprehensiveness, solidity, power. He fights the Army of the Potomac, his decisions, of course, being subject to modification by the supervision mind of his superior officer, with whom he is always in close counsel. He is called George the Meade, by the soldiers, and they love him. As I studied the features of those two men, it seemed as if I stood on firmer ground. I felt that there was the combination that through a favoring Providence would give us victory.

This feeling pervades the entire army. It has gone far toward buoying them up in the arduous toils of the present campaign. It has nerved them in the shock of battle. If they are ordered into the jaws of death, they know it is no needless slaughter. If they are sent on some wearisome marches, they believe it is to secure a more effective blow to treason. The have confidence in their Generals. They trust their leadership. They expect success, and they crossed the Rapidan to secure it or die. There is very little old-time lightness and “Hurrah boys,” and wild enthusiasm of other campaigns. A serious, sober, determined purpose has settled down upon the army. Some of the men are stern to awfulness; and every day’s advance has deepened the conviction among the rank and file, that a master mind is at the head of affairs. The people may be sure of this. Our soldiers are hopeful and confident. They will swerve not. They will falter not. If their prowess wring not victory from the rebel host, it will be because God has a still bitterer baptism with which to baptize the nation.

From Massaponax Church the army advanced to Guinea Station and so on to the left, meeting with no material opposition until reaching the North Anna.

The assessment of Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter of Grant’s convictions, leading to Grant calling the Council of War

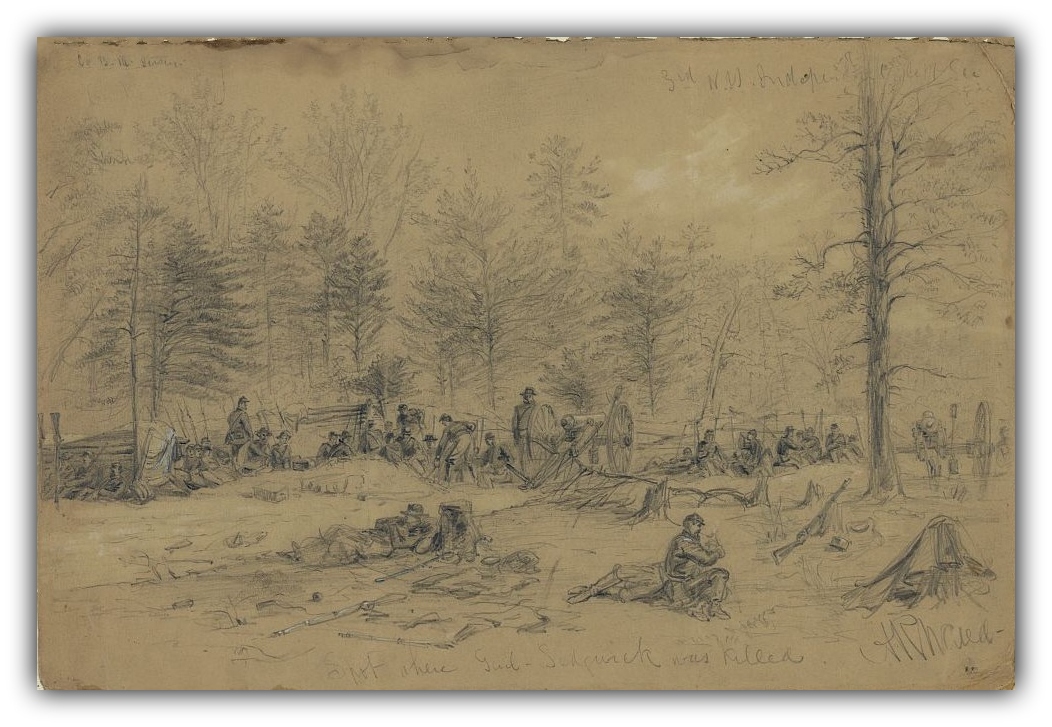

Headquarters were this day moved about a mile and a quarter to the southeast, to a point not far from Massaponax Church. We knew that the enemy had depleted the troops on his left in order to strengthen his right wing, and on the night of the 17th Hancock and Wright were ordered to assault Lee’s left the next morning, directing their attack against the second line he had taken up in rear of the “angle,” or, as some of the troops now called it, “Hell’s half-acre.” The enemy’s position, however, had been strengthened at this point more than it was supposed, and his new line of intrenchments had been given a very formidable character. Our attacking party found the ground completely swept by a heavy and destructive fire of musketry and artillery, but in spite of this the men moved gallantly forward and made desperate attempts to carry the works. It was soon demonstrated, however, that the movement could not result in success, and the troops were withdrawn.

When General Grant returned to his headquarters, greatly disappointed that the attack had not succeeded, he found dispatches from the other armies which were by no means likely to furnish consolation to him or to the officers about him. Sigel had been badly defeated at New Market, and was in retreat; Butler had been driven from Drewry’s Bluff, though he still held possession of the road to Petersburg; and Banks had suffered defeat in Louisiana. The general was in no sense depressed by the information, and received it in a philosophic spirit; but he was particularly annoyed by the dispatches from Sigel, for two hours before he had sent a message urging that officer to make his way to Staunton to stop supplies from being sent from there to Lee’s army. He immediately requested Halleck to have Sigel relieved and General Hunter put in command of his troops. General Canby was sent to supersede Banks; this was done by the authorities at Washington, and not upon General Grant’s suggestion, though the general thought well of Canby and made no objection.

In commenting briefly upon the bad news, General Grant said: “Lee will undoubtedly reinforce his army largely by bringing Beauregard’s troops from Richmond, now that Butler has been driven back, and will call in troops from the Valley since Sigel’s defeated forces have retreated to Cedar Creek. Hoke’s troops will be needed no longer in North Carolina, and I am prepared to see Lee’s forces in our front materially strengthened. I thought the other day that they must feel pretty blue in Richmond over the reports of our victories; but as they are in direct telegraphic communication with the points at which the fighting took place, they were no doubt at the same time aware of our defeats, of which we have not learned till to-day; so probably they did not feel as badly as we imagined.”

The general was not a man to waste any time over occurrences of the past; his first thoughts were always to redouble his efforts to take the initiative and overcome disaster by success. Now that his cooperating armies had failed him, he determined upon still bolder movements on the part of the troops under his immediate direction. As the weather was at this time more promising, his first act was to sit down at his field-desk and write an order providing for a general movement by the left flank toward Richmond, to begin the next night, May 19. He then sent to Washington asking the cooperation of the navy in changing our base of supplies to Port Royal on the Rappahannock.

In discussing the contemplated movement to the left, General Grant said on the morning of May 20: “My chief anxiety now is to draw Lee out of his works and fight him in the open field, instead of assaulting him behind his intrenchments. The movement of Early yesterday gives me some hope that Lee may at times take the offensive, and thus give our troops the desired opportunity.” In this, however, the general was disappointed; for the attack of the 19th was the last offensive movement in force that Lee ventured to make during the entire campaign.

With all the Army of the Potomac had just endured during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, with the just received dispatches regarding Sigel’s defeat at New Market, Butler’s defeat at Drewry’s Bluff and Banks defeat in Louisiana, one would think that Grant would be reticent to move forward quickly. That, however was not in Grant’s character. As Porter recorded; Grant “determined upon still bolder movements on the part of troops under his immediate direction.” It was this resolute determination that demanded Grant call the Massaponax Church “Council of War”.

Plan of the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House

From May 8-21, 1864, Spotsylvania Court House was the site of possibly the most vicious hand-to-hand combat of the Civil War. The Photographic History of the Civil War, published in 1912, depicts the battle as “the most awful in duration and intensity in modern times…”4 with 18,000 Union casualties and an estimated 9000 Confederates killed or wounded. Grant’s object was to break Lee’s communications with Richmond. During early May 1864 the official correspondence of both Grant and Lee was postmarked “Spotsylvania Courthouse.” Grant was quoted in one of numerous diaries published after the war as saying “the Courthouse must be taken at all hazards.”1 Civil War maps indicate that one of the major defense lines of Lee’s forces ran immediately east of the village between the courthouse and the present Confederate cemetery.2 The consensus among historians of the battle is that neither side gained very much from the eight days of ferocious fighting. In describing the Union forces’ attack on the “Spotsylvania Salient,” a member of the 20th Massachusetts Regiment said: “it was the largest body of men ever organized on the continent to launch a single blow.3

By nightfall on May 6, 1864, the battle of the Wilderness had ended in a stalemate, and on May 7 the opposing armies skirmished while for the most part remaining behind hastily built earthworks. Union losses in the Wilderness were reported as 17,666 men killed, wounded, or missing, while Confederate casualties are estimated to have totaled about 11,000. The Union casualties exceeded those of the battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, which had ended with the Army of the Potomac under Joseph Hooker retreating across the Rappahannock River. Determined to continue the campaign until Lee was defeated, Grant issued orders on the morning of May 7 for the army to march that night to the crossroads at Spotsylvania Court House, ten miles to the southeast. 4

May 7, 1864 – Prelude to the Battle – Grant’s Orders to Position at Spotsylvania Courthouse

HEADQUARTERS, ARMIES U.S.

May 7, 1864 6:30 A.M.

MAJOR-GENERAL MEADE, Commanding Army of the Potomac

Make all preparations during the day for a night march to take position at Spotsylvania Court-House with one army corps, at Todd’s Tavern with one, and another near the intersection of Piney Branch and Spotsylvania road with the road from Alsop’s to Old Court House. If this move is made the trains should be thrown forward early in the morning to Ny River.

I think it would be advisable, in making the change to leave Hancock where he is until Warren passes him. He could then follow and become the right of the new line. Burnside will move to Piney Branch Church. Sedgwick can move along the pike to Chancellorsville, and on to his destination. Burnside will move on the plank-road to the intersection of it with the Orange and Fredericksburg plank road, then follow Sedgwick to his place of destination. All vehicles should be got out of hearing of the enemy before the troops move, and then move off quietly.

It is more than probable that the enemy concentrate for a heavy attack on Hancock this afternoon. In case they do we must be prepared to resist them and follow up any success we may gain with our whole force. Such a result would necessarily modify these instructions.

All the hospitals should be moved to-day to Chancellorsville.

Respectively, etc., U.S. Grant, Lieut.-General5

All preparations for the night march had now been completed. The wagon-trains were to move at 4 P. M., so as to get a start of the infantry, and then go into park and let the troops pass them. The cavalry had been thrown out in advance; the infantry began the march at 8:30 P. M. Warren was to proceed along the Brock road toward Spotsylvania Court-house, moving by the rear of Hancock, whose corps was to remain in its position during the night to guard against a possible attack by the enemy, and afterward to follow Warren. Sedgwick was to move by way of Chancellorsville and Piney Branch Church. Burnside was to follow Sedgwick, and to cover the trains which moved on the roads that were farthest from the enemy.: Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter from his memoir Campaigning with Grant, 1897

MOVEMENT FROM THE WILDERNESS

AN OVERVIEW FROM THE DAILY NATIONAL INTELLIGENCER AND WASHINGTON EXPRESS6

At noon on Sunday the headquarters of General Grant were at Piney Branch Church, six miles south of Chancellorsville. A dispatch dated at that place at twelve o’clock on Sunday May 8 says:

“The whole army moved out of the Wilderness last night and will be encamped to the right and left of Spotsylvania Court-House to-night. Our cavalry is covering the advance of the army encountered mounted forces of the enemy on several roads and skirmished with them all day, driving them steadily. The advance of the army southward will continue to-morrow. There is no sign of the main rebel army either on our flank or on our front. All the Western regiments in the Army of the Potomac were engaged in the last week’s battles. The 14th and 20th Indiana suffered very severely, the latter losing one hundred and eighteen killed and wounded, including six officers.”

THE BROCK ROAD, TODD’S TAVERN & PINEY BRANCH CHURCH MAY 8, 1864

A letter to the New York Herald dated at Piney Branch Church on Sunday, the 8th instant, says:7

“We left our last headquarters at Wilderness run last night at dark, and to our present position, reaching here at nine A.M. Gens. Grant and Meade came by way of the Old Brock road and Todd’s tavern, a distance of some twelve miles.

“The Brock road makes off from the Fredericksburg and Orange plankroad about a mile east of the intersection of the Culpeper and Fredericksburg and Orange Court-House turnpike and leading directly to Spotsylvania Court-House.

“The Second Corps at dark took up its line of march by way of Brock road, followed by Warren’s Fifth Corps on the same route. Sedgwick and Burnside took the old Chancellorsville road, and came forward, arriving on the field near Spotsylvania at noon to-day.

“Warren proceeded to a point about two miles from Spotsylvania Court-House, where he came up with the cavalry, who were engaging the enemy. He immediately set to work, and a terrific contest is now going on.”

The particulars of this fight are related by another correspondent, accompanying the Fifth Corps, from whose letter we extract the following:

“This corps has again been heavily engaged to-day. The closest and severest contest of the day has only just ended. Our column marched all night. It was the last to leave the entrenchments where the battles of the Wilderness were fought; and, first in the fight there, was first also in the fight here.

“Taking the Brock road, by way of Todd’s tavern, and moving separate from trains, our march was unobstructed and rapid. It was not known, of course, where we would meet the enemy. A rumor prevailed that only Ewell’s corps was staying behind, and that rest of the rebel army was hurrying, with all possible speed, to resist the advance of Gen. Butler’s forces on Richmond. The day’s events developed a different state of affairs.

“There had been a cavalry fight in front of us, and a report came to General Warren that only cavalry and some artillery had been seen, and prisoners said there was no infantry near us. The result showed this statement to be incorrect. Advancing from Todd’s tavern, on the road to Spotsylvania Court House, four regiments of General Bartlett’s brigade, of General Griffin’s division – the 21st Michigan, 44th New York, 83rd Pennsylvania, and 18th Massachusetts regiments-were sent ahead as skirmishers. As we passed down the road shells were hurled at us with great rapidity. General Warren and staff were advancing down the same road.

“As we advanced the enemy fell back, making only slight resistance. Reaching what is called Alsop’s Farm, we came into a clearing of about a hundred acres, and triangular in form. The rebel artillery had been stationed in this clearing. To the rear of the clearing is Ny Run, a small stream, affording no obstacle to the advance of the troops. The woods are a mixture of pine, cedar, and oak, but not so dense as the scene of our late battles. The wooded ground rises beyond the Run and is ridgy. At the opening into the clearing the road forks, both leading to Spotsylvania Court-House, some three miles distant from this point.

“The battle line as formed comprised Gen. Griffin’s division on the right and Gen. Robinson’s on the left. The enemy’s artillery was now located in a small clearing on the ridge fronting us. The line of battle advanced through the clearing. Having driven the enemy up to this point, two miles into the woods fronting us, our forces pushed them; and now began the serious opening of the day’s work. Our troops ran on to three lines of the enemy, the last behind earthworks. Two corps of the enemy – Ewell’s and Longstreet’s – as was afterwards ascertained, were here awaiting us. The fight was terrible. The remaining divisions of the corps – Gen. Crawford’s and Gen. Wadsworth’s, the latter now commanded by Gen. Cutler – were hurried forward rapidly. The fight became general and lasted four hours. Our troops behaved magnificently, keeping at bay more than treble their number. It will be understood that the remaining corps of the army, which had taken the road by way of Chancellorsville for this point, were still behind.

“This opening fight commenced about 8 A.M. In the afternoon there was a succession of other battles, the Fifth still being engaged. Just before night one brigade of the Sixth Corps went to the assistance of the corps, and, with this exception, the Fifth did all the day’s fighting. The closing struggle of the day was, if anything, more desperate than the one in the morning. The fiercest effort was made by the enemy to drive us back and get on our flanks; but the coolness and courage of our men repelled every effort.

“We have beaten the enemy, but it has been a most costly victory. Our losses are get down (sic.) as thirteen hundred – killed, missing, and wounded. To-night our division is commanded by a colonel. Brigades have lost their commanders, and I know of one regiment – the Fourth Michigan – that is commanded by a first lieutenant. Gen. Robinson, early in the engagement of his division, was shot through the knee. The bone is thought to be shattered, and that the limb will have to be amputated. Col. Coulter now commands the division. Col. Dennison, commanding the third brigade of the fourth division, is wounded in the arm. Capt. Martin is slightly wounded in the neck. His battery lost two killed and seven wounded. Among the killed is Col. Ryan, 140th New York. He was formerly Assistant Adjutant General of Gen. Sykes, was a graduate of West Point, and a young and most promising officer. Major Stark, of his regiment was also killed.

“Several regiments have suffered terribly. The First Michigan, which went in with nearly two hundred men, came out at the end of the closing fight with only twenty-three men left. The Thirty-second Massachusetts regiment, Col Prescott, captured the Sixth Alabama regimental flag.

“At half-past five o’clock P.M. both Lieut. General Grant and General Mead visited the scene of action. They road directly to the front. Not only did the troops not engaged cheer them lustily, but the men in battle, knowing their presence, fought with more determine desperation.”

THE FIELD OF BATTLE ON MONDAY MAY 9 – DISPATCH FROM THE CORRESPONDENT OF THE BOSTON JOURNAL8

The battle-field is a series of ridges mostly covered with woods and fine thickets, in which the rebels lay concealed with batteries masked. Standing in the centre of our line, between the Fifth and Sixth Corps, on Piney Grove (Branch) road, looking toward the Court-House, you see a gentle slope with a series of undulations, marked with rifle pits and batteries, which defends all approaches. To gain them there must be hard fighting at every step. The thickets are not quite so dense as in the Wilderness, but most of the ground is covered by forest.

Lee had pushed his troops rapidly into a strong position on the south bank of the Po. The Court-House is on elevated land, and the village is a collection of half a dozen houses. Three roads radiate – one northwest to Todd’s Tavern, one due north to Piney Grove (Branch) Church, and one northeast to Fredericksburg.

The Second and Fifth Corps covered the way to Todd’s, the Sixth the road to Piney Branch, and the Ninth the road to Fredericksburg. The Catharpen road, leading westward, was used by Lee to reach the position.

A FIGHT ON MONDAY MAY 9, 1864.9

Reports from the army state that on Monday all was quiet along our lines till late in the afternoon, when, a forward movement having been determined on, it was commenced at half-past five o’clock, the right consisting of Generals Birney and Gibbon’s divisions of the Second Corps and Carroll’s brigade on the left, joining Warren’s, the latter being the centre, with the Sixth Corps on the left. The right crossed a branch of the Po river and charged on a light horse battery which was posted to cover a small bridge, but which quickly limbered up and started off, the skirmishers supporting it also retreating. In front of Warren, on the left of Gen. Hancock, quite a lively engagement ensued. The enemy were driven back about three-fourth of a mile, and at dark the firing ceased. A few prisoners were captured. They belonged to Wilcox’s division of Hill’s Corps. It was believed that Longstreet’s Corps was the only one in our front, and that he was left there to impede our progress as much as possible.

On Monday night, about 11 o’clock, the rebels in front of Gen. Warren’s corps made an assault on a line of rifle-pits hastily constructed. Our men gave them a volley and fell back for the purpose of drawing them on to a second line. The ruse was successful, and as the rebels advanced, they were received by a destructive fire, which drove them back in disorder. But finding our men still retiring they followed and made a charge on the third line. Here the whole of our line gave them a raking fire and then charged and drove them back in utter disorder. Their loss was quite heavy, while our own was light. We also took a number of prisoners.

THE SITUATION ON MONDAY.

A letter to the Herald, dated on Monday, the 9th, this alludes to the situation at that time:

It appears by a dispatch of Mr. Secretary Stanton to Gen. Dix that Gen. Grant was preparing on Monday for a further advance. The Secretary, writing on Tuesday night, says:

“We have now been out six days and have been fighting continuously. We have succeeded in penetrating some fifteen miles into the rebel territory and have fifty miles further to go to get Richmond. We have eaten and used up a very large portion of the supplies which we took with us. If the rebels give us as much trouble on the rest of the route as they have thus far our chances for success are slim indeed. Our losses have been terrible. I hardly dare to give my own opinion as to the numbers; but I think I am within bounds when I give the estimates of those who are supposed to know, as follows; Killed, three thousand; wounded, eighteen thousand; missing, six thousand. Total, twenty-seven thousand.

PREPARATIONS FOR ANOTHER BATTLE.

“Dispatches have been received this evening from Major General Grant, dated one o’clock yesterday. The enemy have made a stand at Spotsylvania Court-House. There had been some hard fighting, but no general battle had taken place there.

“I deeply regret to announce that Major General Sedgwick was killed in yesterday’s engagement at Spotsylvania, being struck by a ball from a sharpshooter. His remains are at Fredericksburg and are expected here to-night.

“The army is represented to be in excellent condition, and with ample supplies. Gen. Robertson and Gen. Morris are wounded. No other casualties to general officers are reported. Gen. Wright has been placed in command of Sedgwick’s corps.

“Gen. Grant does not design to renew the attack today, being engaged in replenishing from the supply train, so as to advance without it.”

MOVEMENTS ON TUESDAY MAY 10, 1864 – OUR LOSSES

From a special dispatch to the Chronicle, dated at the Headquarters of the Army on Tuesday, the 10th instant, we extract the following:

“The Army of the Potomac has had a portion of a day to recuperate. Indications are that the rebels will fall back to their formidable fortifications near Hanover Junction.

“To-day Gen. Burnside began the attack on the left with great fury and an encouraging degree of success. He had a fight the day before, in which, to use his own words, he ’whipped old Longstreet.’

“A courier came in from Gen. Butler yesterday. About fifteen thousand cavalry, under Gen. Sheridan, started soon after. They will engage the rebel cavalry, circum-navigating Lee’s army, and join Butler. Our army could not be in a more cheerful condition. Every man is sanguine of success, and they count the days when they shall in triumph enter the rebel metropolis. All the battles thus far have been a series of attacks and repulses. Musketry was almost entirely used. The ground being swampy, artillery was impracticable.

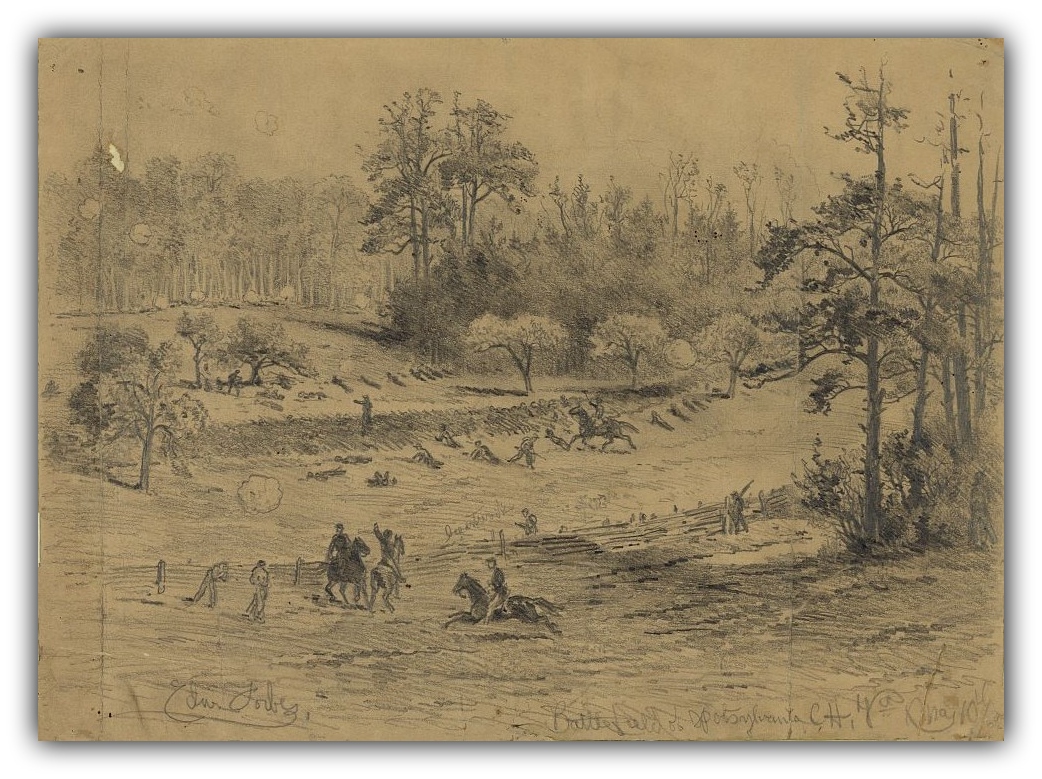

“Lee very absurdly claims a victory when he withdrew from our front and marched toward Richmond. Our army moved with them along parallel roads, coming in deadly contact with them at Todd’s Tavern, near Spotsylvania Court-House. Gen Torbett’s division of cavalry whipped the rebel cavalry near this place and drove them from Spotsylvania Court-House. But, reinforced with infantry, they drove our cavalry a short distance – the Maryland brigade, fourth division, sixth corps, coming in their support. The fighting was exceedingly fierce. Gen. Torbett and Gen. Robinson were both wounded and are now on their way to Washington.

“I regret to announce the death of so valuable and efficient an officer as Gen. Sedgwick. He was shot through the head this morning, while superintending the mounting of some heavy guns in an angle the men had just prepare. There was no skirmishing at the time, but an occasional sharpshooter sent a bullet in that direction, which caused the cannoneer to wince and dodge. Gen. Sedgwick was nearby, with some of his staff, and twitted the man about his nervousness. ‘Pooh! Man,’ he said, ‘they can’t hit an elephant at that distance.’ Immediately after, the ball struck him, and the blood began to ooze from his nostrils. He smiled serenely and fell dead in the arms of his assistant adjutant general. His body, and Gen. Hays’s, have been forwarded to Washington.

“The hemorrhage in the rebel army has been horrible, while our own is of no mean magnitude. All through the Wilderness they are strewn, and fires kindled by the bursting of shells consumed the mangled bodies of the antagonists. In these several encounters with the rebels we have lost the present use of over thirty-five thousand men. In Fredericksburg, at this writing, there are over twelve thousand of our wounded. Sunday morning, they began crowding into town. Mr. Slaughter, Mayor of the city, and Mr. Marye, of the celebrated heights near Fredericksburg, in the full zeal of their patriotic hearts, rallied a few guerrillas and marched three hundred of our wounded into the rebel lines. Poor fellows, theirs is a sad fate! Hungry, thirsty, and weary they were captured. How much worse are they now! Mayor Slaughter and several other prominent citizens are now in the guard-house at Fredericksburg. Pontoons float on the Rappahannock, below Fredericksburg. To Aquia Creek, where the transports lie, is eight miles. Guerillas abound throughout the country.

“This movement across the Rapid Ann is the most brilliant and daring in the annals of the war. Nothing could be more dangerous than a flank movement by our army while Lee was in front with his long heavy lines. Every officer and soldier is sanguine. The utmost confidence is reposed in Grant and Meade.”

THE BATTLE OF TUESDAY, MAY 10, 1864.10

On Tuesday skirmishing commenced at sunrise and continued through the forenoon along the whole line with increasing intensity. At first it was supposed that there was only a small force in our front, but at noon it became plain that Lee was making a most desperate effort with his whole army to beat our forces back.

Our position was a mile north of Spotsylvania Court-House. The rebels held a strong position on the south bank of the Po river.

The Second Corps had its right on the road leading to Todd’s Tavern. The Fifth and Sixth had the centre, and the Ninth held the left on the Spotsylvania and Fredericksburg road. The line of battle was six miles long.

Gen. Grant spent all the forenoon examining the positions and was frequently on the line with the pickets. He issued orders for a general attack at five o’clock, but the rebels grew uneasy – took the matter into their own hands and moved in heavy columns against Hancock’s left and Warren’s right. The first division of the Second Corps (Barlow’s) was fought back to the north side of the creek to a strong position. The rebels were elated and attempted to cross the creek but were repulsed. Up to this hour there had been little artillery used by either party, but battery after battery was brought into position against Hancock, and then against Warren, but were immediately rolled back. Gibbon, commanding the second division of the Second Corps, was withdrawn from Todd’s Tavern road and sent to Warren’s aid.

At 3:30 the rebels made a terrific charge against our right centre. Their hurrah was the war whoop of the Indians, but it did not intimidate the brave men of the Second and Fifth Corps. I never heard a heavier fire than that which burst from Birney’s, Cutter’s, Gibbon’s, and Barlow’s divisions. The rebel columns pelter away, and, after one of the most desperate fights of all time, were forced back under the tremendous fire and unflinching bravery of the divisions already named. Parts of other divisions were engaged, but not to such an extent as these.

It was Hancock’s turn. His troops advanced with cheers. Barlow’s division fell upon Heth’s division of Longstreet’s corps like a thunderbolt, cutting it all to pieces. Rebel prisoners say it was the greatest charge of the war. The rebels were literally piled in heaps.

The advance of other parts of the line not having been made at the appointed moment, the advantages gained were lost, and the Second returned to its former position. There was no further attempt on the part of the rebels to push the Second Corps.

Just before sunset Wright and Burnside attacked the enemy with great fury. Wright carried their rifle pits. The Second Vermont held one against all efforts of the rebels to retake it. They said they would hold it for six months, only give them plenty of ammunition and rations. Gen. Wright, at nine o’clock, went to headquarters and reported their gallantry, asking for instructions whether they should hold it. “Pile in the men and hold it at all hazards,” was Grant’s reply. Gen. Wright went back to execute the order, but found that some subordinate officer had ordered them back for fear they would be cut off. Glorious sons of a glorious state! Their honor is untarnished. Their laurels can never fade!

Burnside pushed the enemy back almost to the Court-House and held his ground when I left the field this morning. The colored troops were not in the charge!

Upton’s brigade, of the Sixth Corps, captured Dale’s brigade of Ewell’s Corps, but in the melee were able to bring off only twelve hundred. Three guns were taken and lost again. Thirty-seven officers and a large number of battle-flags were taken.

We have lost twelve Generals. Sedgwick, Wadsworth, Stevenson, Hays and Rie killed; Barlett, Getty, Robinson, Morros, and Baxter wounded, Seymour and Shaler missing. Our losses of men are very heavy. We have about four thousand prisoners.

Rebel prisoners report that they have been on half rations, and that rebel officers told them their next rations must come from Grant’s stores. None had been issued except to prisoners up to 10 o’clock this (Wednesday) morning. On the contrary, thirty of Lee’s wagons fell into our hands last night.

A dispatch to the New York Tribune gives the following account of this terrific engagement.11

At half past one o’clock yesterday (Tuesday) the most desperate of all the battles yet fought was commenced. It continued up to nearly eight o’clock. In dogged stubbornness, Waterloo and Solferino pale before the terrific onslaught of Tuesday afternoon on the banks of the Po.

Two divisions of Burnside’s corps held the right, the Fifth and Sixth Corps the centre, and the Second Corps the left. Our line stretched six miles on the northeast bank of the Po, the rebels occupying the southwest bank and the village of Spotsylvania.

At two our artillery gained a good range, and poured shot and shell, grape and cannister into the enemy’s ranks, as they, with frantic recklessness of life, charged forward upon our infantry lines. The enemy used but little artillery in reply. Prisoners state that they were deficient in ammunition and could not.

The impression prevailed at headquarters during the fore part of the day that Ewell’s corps had left for Richmond. All prisoners taken were from Longstreet’s and Hill’s corps, but before yesterday’s battle closed Ewell returned – if he had left, as is probable – and Lee’s entire army and our whole force were pitter for three hours at a hand-to-hand struggle.

Gen. Grant and Gen. Meade were in the saddle constantly, personally directing movements.

It was arranged that the entire Ninth Corps should charge the enemy’s right flank, but, pending the severest onslaught made by Lee just before dark, it was discovered that he had advanced around our right flank and was moving down in dense columns for a last and after dark struggle to break through our lines and dash upon our supply trains, then known to be packed on the plank road to Fredericksburg. This changed Gen. Burnside’s purpose, and he securely held his ground and threatened the enemy’s extreme right, while the Sixth Corps charged his right centre, and (at seven o’clock) drove him from his first line of rifle pits, capturing five guns and between two and three thousand prisoners.

The quick eyes of our chieftains, however, saw the rebel maneuver. Our men were faced about, our trains all moved to the rear, new positions instantly secured for our artillery, and the enemy’s expected coming patiently awaited during all the long hours of last night. No demonstrations were made, however, and, except the occasional shouts of pickets, all was quiet up to eight o’clock to-day (Wednesday) when I left.

It was believed that the enemy had suffered so severely that he could not, in his crippled condition, avail himself of the decided advantage he had gained. By others it was supposed he had attempted another flight, but as his communication with Richmond is believed to have been severed by Sheridan, and his flanks and rear constantly harassed by our forces, he must surrender or kill his “last man” in battle, as he seems determines in frantic rage to do.

In so horrible a strife it must not be supposed that we escape the severest punishment. Our losses in yesterday’s fight were much greater than in any of the battles of the previous week. It is true there is a smaller percentage of killed in proportion to the number wounded than in any previous battle, and a very large number are but slightly wounded. Roads, fields and woods are literally swarming with those suffering heroes, who have defied wounds and death that the nation might survive. So incessant have been the marching and fighting that many are being overcome with fatigue, and several have been sun-struck; yet never was seen so cheerful, so resolute, and even exultant a body of men on any of the world’s great battle fields. All honor to this sublime heroism, which so nobly welcomes death and wounds.

Rebel prisoners assert that Lee ordered all his wounded men able to hold a musket to take their places in the ranks again for yesterday’s battle.

Our wounded are conveyed with all possible dispatch to Fredericksburg, and thence, by way of Belle Plain, to Washington. But for a tender regard for these disabled heroes, abandoned to their fate and burning up in the woods, left on fire, (as the rebels also leave their dead unburied,) our army ere this have been thundering before the rebel capital. But we can afford to wait. Men who have faced musketry and cannon for a week, and fought better each succeeding day, are invincible, and they will soon with the complete triumph their valor so richly merits. Time after time did they hurl back in disorder the solid massed columns of the foe, and if perchance they staggered with the shock, it was only for more super-human energy to charge back upon him. The old guard at Waterloo pales before these men.

Our entire losses thus far, in killed, wounded, missing, &c, must reach near forty thousand. The enemy’s loss in killed is much greater than ours; his wounded about the same. He is supposed to hold some two thousand of our prisoners, and we must have at least five thousand of his men, while our scouts report the roads literally alive with his stragglers. It is a mathematical question requiring only a few more days to determine the limit of his endurance.

Thus far we have not lost a gun since the second day at the Wilderness, for a single wagon since the campaign opened. Up to Monday night the reserve artillery had not been brought into fire.

All prisoners unite in asserting that Lee is dumbfounded at the present conduct of our army. Immediately upon his getting orders from Jeff. Davis to return to Richmond, and withdraw from our front at the Wilderness, he dispatched a brigade across the Rapid-Ann, and planted artillery so as to command Germanna ford, supposing that we were to pursue our usual course of fighting and then falling back. The brigade remained there one day and two nights without any chance of attacking our retreating columns and only had the effect of turning back our wounded. The pertinacity with which Grant hangs to him is so unusual and so unexpected, that Leed is perfectly bewildered.

SKIRMISHING ON WEDNESDAY MAY 11, 186412

The army was comparatively quiet during Wednesday. A letter dated at seven o’clock in the evening says:

Our position is the same as at the close of yesterday’s battle. There has been active skirmishing nearly all day, but no general engagement. Our batteries at intervals have shelled the enemy to prevent his throwing up earthworks, which he attempted to do.

The story reached us that the enemy was going to make a general attack this afternoon, and if he failed to break or turn our lines, that he would give up fighting our army here and hurry to the rescue of Richmond. The attack, if any was contemplated, has not been made. At all events, it is the general opinion here that if Gen. Lee wants to go to Richmond, and take his army with him, that Gen. Grant will insist on having a word to say in that matter. If Gen. Lee attempts the draw game he will find an opposing general who is up in dodges too, and an army that can travel as fast as his. Our army is satisfied with the position the rebel army now holds, or any position it can place itself in. It is only a question of time and prolonged pounding; and which army has the most time at command can stand pounding the longest. Our army has no notion of giving up. It is no hackneyed stereotypism, but a stubborn fact, that the army is in excellent spirits.

The number killed is much below the usual percentage, and the number of officers killed and wounded, compared with the killed and wounded of the privates, bears nothing like the average proportion to the corresponding losses shown in other fights.

A refreshing thunder storm, the first rain we have had since the commencement of the present campaign, visited us this afternoon. It was most welcome, cooling the air, whose warmth and closeness has caused much suffering to our troops, and laying the dust.

On Wednesday evening the following dispatch of Gen. Sheridan to Gen. Meade was read to the troops.

HEADQUARTERS CAVALRY CORPS, May 10, 1864

Major Gen. Meade, Headquarters Army of the Potomac

GENERAL: I turned the enemy’s right and into their rear. Did not meet sufficient calvary to stop me. Destroyed from eight to ten miles of Orange railroad, two locomotives, three trains, and a very large amount of supplies. The enemy were making a depot of supplies at Beaver Dam. Since I got into their rear there has been great excitement among the inhabitants and with the army. The citizens report that Lee is beaten. Their cavalry has attempted to annoy my rear and flank but have been run off. I expect to fight their cavalry south of South Anna river. Have recaptured five hundred of our men – two colonels.

Very respectively, your obedient servant, P.M. Sheridan, Major General Commanding.

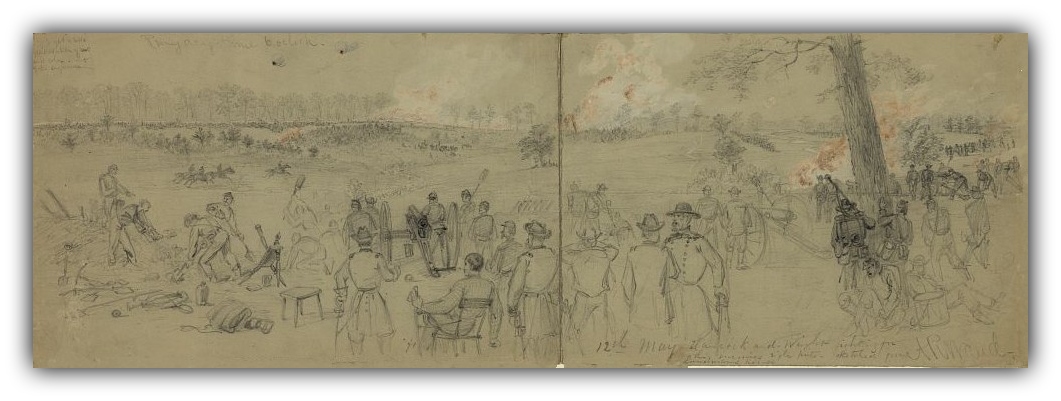

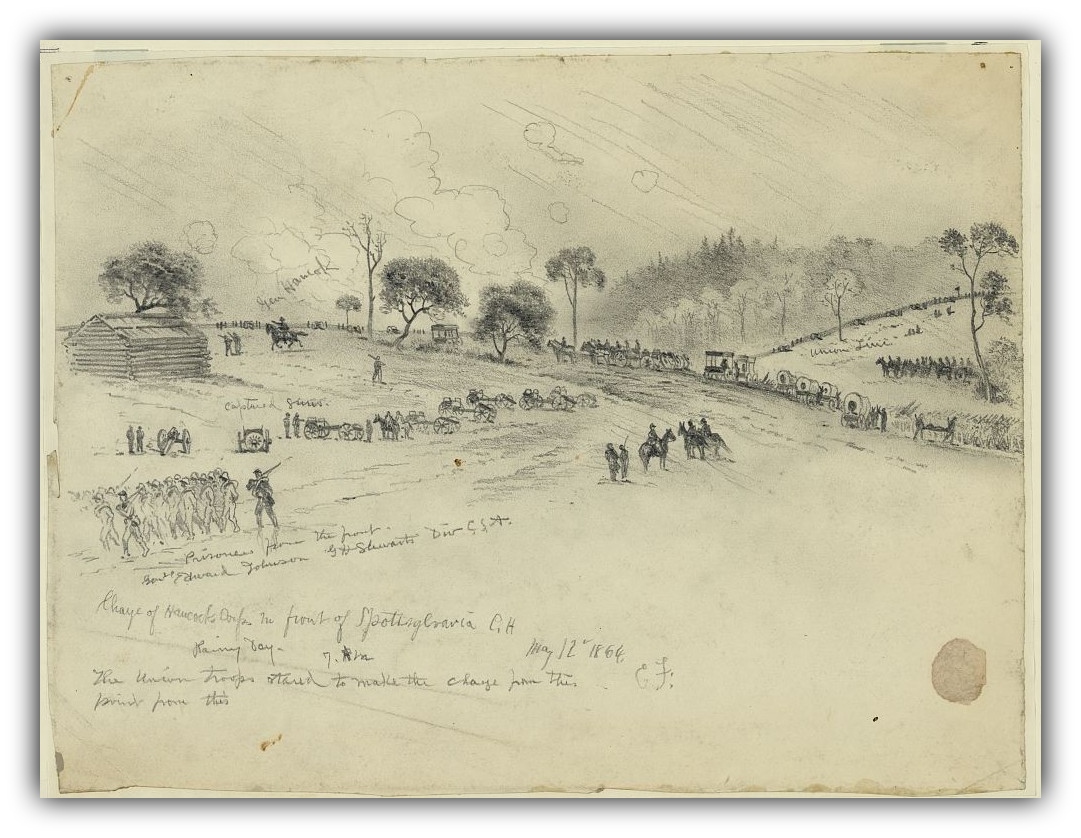

A GREAT SUCCESS ON THURSDAY, MAY 12, 186413

During Wednesday night Gen. Hancock changed his entire position, his operations being concealed under cover of the rain, darkness, and fog, and early on Thursday morning he gained a position from which he made a dash upon the line of the enemy’s entrenchments, completely surprising them and capturing many guns and a large number of prisoners.

A dispatch from the correspondent of the New York World, writing from the headquarters of the army on the field near Spotsylvania, relates some of the particulars, as follows.14

The enemy (during Wednesday evening) had been pushing troops toward our right, and ostentatiously erecting abattis in front of Hancock’s troops. It was shrewdly, and, as the event showed, rightly suspected that this was only a blind. The real attention of the enemy was therefore anticipated.

After midnight the Second Corps (Hancock’s) was pushed to the left of the Sixth Corps, (Wright’s,) between that and Burnside’s command, and on the left of the Spotsylvania road.

At half-past four o’clock this (Wednesday) morning Hancock attacked the enemy fronting him, our force opening a withering cannonade and making resistless charges against the very heart of his position. The cannonade was replied to with vigor. The charges of our men were as vigorously resisted; but the determination of the onset overwhelmed everything. The troops rushed in on the rifle-pits of the enemy, bayonetting them in their works, cutting their lines, and capturing on the first charge over three thousand men and several guns, including the greater portion pf the “Stonewall Brigade,” belonging to the division commanded by Gen. Ned Johnson, and forming part of Ewell’s corps. Gen. Johnson himself was taken prisoner. The assault was continued till nearly the whole division of the corps was captured and other troops, amounting in the aggregate to a thousand men.

A later dispatch from the same correspondent, dated at 11 o’clock on Thursday, says:15

A dispatch arrives at this moment announcing the capture of seven thousand prisoners and thirty guns. The battle is still progressing. The Sixth Corps, on the left of the Second, has moved into battle, and are also pushing the enemy. Gen. Warren, Fifth Corps, moves up to its support on the right. The battle is becoming general. Nearly all our artillery is engaged, and the clangor of the guns, the whistle of grape and solid shot, the roar of musketry, and the explosion of the enemy’s shells, fill miles of forest with awful tumult. The shells burst around me while I write.

A dispatch dated an hour later, at twelve o’clock noon, from the same correspondent, says:

It is just now reported that Hancock has turned the right flank of the enemy below Spotsylvania Court House and is pressing on. The battle is every where overwhelming in our favor. Terrific firing has just commenced on the left, very near Gen. Grant’s headquarters. The battle is going on with terrible energy, and our success is said to be certain. Prisoners are constantly coming in.

The following is a dispatch sent by Gen. Hancock this morning.

Near Spotsylvania Court House. May 12 – 8 A.M.

I have captured from thirty to forty guns. I have finished up Johnson and now going into Early.

W.J. Hancock

The dispatch from the correspondent of the New York World, writing from the headquarters of the army on the field near Spotsylvania, continues:

The guns captured have arrived at headquarters. Brig. Gen. Steuart, commanding a brigade in Johnson’s division, was captured.

Gen. Burnsides’s column is reported to have moved down on the railroad toward Fredericksburg, going in on the enemy’s rear. Gen. Warren, with the Fifth Corps on the right, is now sending heavy lines of skirmishers to feel the enemy’s works in his front, which are supposed to be abandoned.

It is impossible to ascertain all the particulars at the time of this writing, but our victory is considered to be going on to a decisive result. Gen. Wright is slightly wounded, but still in command of the Sixth Corps.

Further Particulars as Reported by the Weekly National Intelligencer for the Battle of Thursday, May 12, 186416

We have already given a detailed account of the splendid success which Hancock’s Corps ushered in the dawn of Thursday morning, resulting in the capture of an entire division and part of a brigade of the enemy, and from thirty to forty pieces of artillery. We are now able to complete the account of the great battle of that eventful day.

It will be remembered that very early in the morning of Thursday Gen. Hancock apprized Gen. Grant of his great success, and added: “I have finished up Johnson, and am now going into Early.” At half-past seven he was still fighting with his accustomed persevering intrepidity, although a furious rain storm, accompanied by heavy thunder and lightning, placed few difficulties in his path. At that hour Warren’s corps, composing the centre of our army, also became briskly engaged, the batteries of the enemy being opened in the meanwhile, and their shot and shell falling fast and furiously around the headquarters of Grant and Meade.

At ten o’clock our whole line was engaged, Hancock and Burnside on the left and front, and Wright and Warren on the right, the enemy fighting with the utmost obstinacy, but without being able to regain from our troops the ground they had taken, or to prevent them from steadily advancing.

At eleven o’clock there was a lull in the battle, with the exception of a vigorous cannonade, which was still kept up.

At one o’clock it became apparent that Warren’s attack on the right had not succeeded, our right wing was drawn back, and Gen. Meade massed our forces upon the left and a vigorous attack was made there.

At two o’clock it had been found impossible to dislodge the enemy from their position – Lee having formed his left in a strong position, his line being covered for its whole length by formidable breastworks.

Later in the day Ewell’s Corps attacked Hancock with furious energy, striving to reverse the success of that able commander in the morning, but without making any decided impression.

Elsewhere the fighting was violent but indecisive until five o’clock in the afternoon, when it became apparent that the enemy were growing weaker.

Towards dark, our centre, for the first time, occupied Spotsylvania village; and at dark we held decided advantages, our line having advanced two or three miles despite all the efforts of the enemy.

The results of the day’s fighting are thus summed up by Gen. Grant, in a dispatch to the Secretary of War, dated near Spotsylvania Court-House, at half past six o’clock in the evening of Thursday:

“The eighth day of the battle closes (he includes fighting in the Wilderness, May 5-12), leaving between three and four thousand prisoners in our hands for the day’s work, including two General officers and over thirty pieces of artillery. The enemy are obstinate and seem to have found the last ditch. We have lost no organization, not even a company, whilst we have destroyed and captured one division, (Johnson’s,) one brigade, (Dobb’s,) and one regiment entire of the enemy.”

The desperate struggle was, however, resumed in the night, after which the enemy commenced falling back. We quote the following dispatch of a correspondent of the Associated Press, dated from the Headquarters of the Army at noon of Friday:

“The Army of the Potomac has achieved the greatest victory of the war, after some of the severest fighting ever recorded in history. The battle of yesterday is acknowledged to be the heaviest of all, lasting from daylight to after dark, renewed about nine P.M. and continuing till three A.M., both parties, during the night, contending for the possession of a line of rifle-pits from which our men had driven the enemy in the morning. The rebels fell back early this morning, and skirmishing is now going on, our troops following them up through the woods.

“The scene presented to-day is entirely beyond description, the dead and dying of both armies lying in the breast works on each side in piles, sometimes three and four deep, and many of them pierced with holes in their bodies. The enemy had removed many of their dead and wounded, during the night, from some portions of the line, but there were pits where they could not reach, and in these places they lay thick as ours.

It was Birney’s division, of the Second Corps, that charged this position, and in doing so lost about seven hundred men. Every regiment in the division distinguished itself, and none bore a nobler part than the 93d New York. Col. Carroll’s brigade aided this division in the charge, and, usual, performed their share with great gallantry. Col. Carroll was wounded a second time, but still keeps on duty.

“The number of guns captures is thirty-nine. Many colors have been taken which have not been brought in, the men wanting to keep them. Carroll’s brigade took a number of prisoners and a stand of colors this morning from a rebel regiment, which they surprised in a piece of woods.”

“The same correspondent, under date of two o’clock in the afternoon, writes that the enemy were found to have fallen back to a new line, abandoning their works on their right, and apparently getting into position for another contest. He forwards the following congratulatory address, issued by Gen. Meade to his troops on Friday morning:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Friday, May 13, 1864

SOLDIERS: The moment has arrived when your Commanding General feels authorized to address you in terms of congratulation.

For eight days and nights, almost without intermission, in rain and sunshine, you have been gallantly fighting a desperate foe, in positions naturally strong, and rendered doubly so by entrenchments. You have compelled him to abandon his fortifications on the Rapid-Ann, to retire and attempt to stop your onward progress, and now he has abandoned the last entrenched position so tenaciously held, suffering a loss in all of eighteen guns, twenty-two colors, and eight thousand prisoners, including two general officers. Your heroic deeds and noble endurance of fatigue and privation will ever be remembered. Let us return to God for the mercy thus shown us and ask earnestly for its continuance.

“Soldiers: Your work is not over. The enemy must be pursued, and, if possible, overcome. The courage and fortitude you have displayed renders your Commanding General confident your future efforts will result in success. While we mourn the loss of many gallant comrades, let us remember the enemy must have suffered equal if not greater losses. We shall soon receive reinforcements, which he cannot expect. Let us determine, then, to continue vigorously the work so well begun, and, under God’s blessing, in a short time the object of our labors will be accomplished.

Geo. G. Meade

“Major General Commanding”

It appears that there was no more fighting either on Friday or Saturday. The Fifth and Sixth Corps had advanced by the left during Friday, and were to have attacked the enemy at daylight, but no enemy was found. Gen. Lee, it is supposed, has fallen back to his second line of entrenchments. The army on Saturday were taking a rest, and the new troops which have joined the army were being assigned positions preparatory to another move forward.

POSITION ON SATURDAY MAY 14, 1864

A correspondent of the New York World, who left the front on Saturday, sends a dispatch from Fredericksburg, bearing Sunday’s date, in which he says.

“Gen. Lee’s entire force fell back on Friday morning some distance, but whether to take up a new position or to make a general retreat was not ascertained up to a late hour in the afternoon of that day. Our army was all south of Spotsylvania.

“No battle was fought Friday, and there was but light skirmishing, which continued during the entire day and through a considerable portion of the night,

“The enemy has again gradually drawn away a portion of his left to a position nearer his base of supplies, but we are pressing him so closely that if he were to weaken his front materially it would be at a great risk.

“A reconstruction of our line was determined upon on Friday night, and before daylight yesterday morning our troops commenced an advance. The rain fell in torrents, and mud on the roads was literally knee deep. Notwithstanding all obstacles and the trying work of the past eight days, our men accomplished their advance with a cheerful alacrity and resolution that entitles them to the highest praise. As it would not be prudent to state with precision the line adopted, it must be sufficient to say that it is the more near the left”

A dispatch from the correspondent of the New York Times speaks as follow of the position of affairs on Saturday night:

“On Saturday night Lee’s forces were believed to be in line of battle about three miles beyond Spotsylvania Court-House, in a southwesterly direction. His sharp-shooters were within half a mile south of town, which was neutral ground.

“Several important changes have been made in the positions of our several corps. It would be improper to state what they are. Suffice it to say that Gen. Grant will bring to bear, in the next attack on the rebel position, superior forces on all sides. Fresh troops are arriving.

“General assault was to have been made on the enemy’s right wing on Saturday morning, but owing to the wretched condition of the roads, which had been rendered almost impassable by the storm, a portion of our army failed to get into position in time, and the attack had to be abandoned in consequence.

“Lee has his forces massed and will give us battle again as soon as we advance. His army, according to the statement of prisoners captured yesterday, is on quarter rations, and without hope of receiving any from Richmond or Lynchburg.”

Another dispatch dated in the field near Spotsylvania Court-House, at six o’clock on Saturday evening, says:

The glorious news of our successes on the 12th instant are fully confirmed by facts. Lee has been constantly, though slowly, driven from one position to another with great slaughter, but continues to fall back on new lines of defenses capable of offering resistance. His present one is on the right flank of the river in front of Spotsylvania Court-House, instead of its rear, as stated in dispatches to other papers.

Friday was incessantly rainy, and all movements were delayed or wholly prevented. The mud very deep, and the roads narrow and miry. The expected attack by us at daylight this (Saturday) morning was unavoidably delayed, owing to the impossibility of getting up artillery, trains, &c.

To-day Lee has been busy entrenching, and his position may have to be turned instead of attacked. Rain has been falling at intervals all day. No fighting of moment.

The enemy made a dash on Wright’s Sixth Corps, and gained momentary advantage at four P.M., but were gallantly repulsed in a few minutes with considerable loss. A battery was planted to annoy our centre, and a column is now marching to capture or drive it away. No general engagement probable to-day.

In a later dispatch from the same correspondent, dated two miles north of Spotsylvania Court-House at ten o’clock in the morning of Sunday he says;

At the date of my last dispatch a column was in motion, led by Gen. Ayres’s brigade, to recapture a strong position in front of our left centre, from which we had been driven by a sudden dash yesterday afternoon. The affair was brilliant and successful. The rebels were driven out precipitously; a large force was put in position, artillery, with infantry supports, planted to command it, and night closed with another decided advantage to our arms. Our loss was light. Gen. Ayres’s orderly and a sergeant commanding a company of the Second United States infantry are among the killed.

The Ny, Po, and Ta rivers form the Matapony, eight or ten miles southeast of this. Lee considered the intermediate country susceptible of defense, and erected substantial earthworks last year immediately in front of our present position. They are sodded and seem to mount heavy guns. Our troops are between the Ny and Po rivers, from one to two miles north of Spotsylvania.

The Second Corps has lost eleven hundred killed, seven thousand wounded, fourteen hundred missing. The Fifth Corps has lost twelve hundred killed, seven thousand five hundred wounded, and thirteen hundred missing. The Sixth Corps has lost one thousand killed, six thousand wounded, and twelve hundred missing. The total losses of these three corps amount to twenty-seven thousand seven hundred. Burnside’s losses are nearly the same proportion and swell the total to about thirty-five thousand. The proportion of slightly wounded is extraordinarily large.

The management of the field hospitals is admirable. The wounded are being sent to Washington by way of Fredericksburg and Belle Plain. Supplies and reinforcements are going forward by the same route.

The erection of the telegraph line from here to Belle Plain commenced to-day. At present dispatch boats run from Washington to the telegraph station, twenty miles below, every four hours. None but government dispatches are allowed to pass over the wires. Appearances indicate the making of Belle Plain a permanent base.

Among the latest unofficial information from this army is a dispatch from Mr. SWINTON, an intelligent and a candid correspondent of the New York Times, coming down to one o’clock in the afternoon of Sunday. He writes from general headquarters, and says that a Sabbath stillness had prevailed during the day up to that hour. On Saturday afternoon the rebels suddenly developed a line of battle on our left, coming through the woods and gobbling up several of our pickets, and driving back the reserve. Gens. Meade and Wright, with the Staff, were out beyond our front at the time, and had a very narrow escape from capture. Immediately afterward Gen. Wright threw forward a force, under cover of artillery fire, and retook the position, which was an important one. Mr. SWINTON also writes as follow:

Although I see announcements in the Northern papers of the rebel army having been driven beyond Spotsylvania Court-House, there is no truth in them whatever, as my dispatches from day to day will have informed you. On the contrary, the enemy continues to strengthen his works. It is fully expected, however, that a vigorous turning movement will complete the evacuation of the rebel lines without a battle.

“The repose of to-day and yesterday is much needed by this army, exhausted as it is by marching and fighting. The mere measurement of the map gives you no idea of the amount of marching the army has been compelled to do. Our lines are from six to ten miles in extent, and corps have been marched and countermarched from one wing to the other. This has ordinarily been done during night, fighting and skirmishing during the day, so that the physical and moral powers of the army have been on the strain for the past twelve days.

“We have met throughout the most obstinate resistance and have suffered much, but you will rightly credit the Army of the Potomac with a substantial success on the whole. The determination to crush out the rebel army is unflagging.”

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Monday, May 16 – 12M.

Our position is not materially changed from yesterday. The enemy has fallen back to a very strong natural position and have kept his forces constantly at work digging rifle-pits and entrenching, notwithstanding the deluging rains of yesterday. All this gives Grant no uneasiness. He is prepared to flank, if need be; and nothing would rejoice his heart more than a siege of Lee, who is weakened by every hour’s delay, while we are strengthened.

Our men need rest; the roads are hub deep with mud, seriously impeding artillery movements and ammunition and supply trains. But the copious rains have been as a cooling lotion upon the wounded. About five hundred of the worst cases of wounded were left in the Wilderness in charge of surgeons. These men have been sent for, and an ambulance train has just left.

It is well known here that we have every advantage to gain by delay, and Lee every thing to lose. Our fresh troops are now rapidly reaching the front and taking position in line. A few guns were fired on Sunday, but nothing of any consequence occurred. Our lines were in the position they occupied on Saturday.

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Tuesday Morning, May 17, 1964.

All rumors of the retreat of Lee’s army toward Richmond are unfounded in fact. The enemy still holds his line northwest of Spotsylvania Court House and is in apparent readiness to accept battle whenever Grant feels disposed to renew the attack.

The recent heavy rains, which have rendered the roads unfit for the passage of artillery, have precluded the possibility of aggressive movements by Grant for the last two days. The full supply of rations is kept up, and no delays of an advance need be apprehended on that score.

Late information gives the assurance that Breckinridge’s and the other rebel forces had not, as was supposed, joined Lee, but they are kept busy guarding the only means of communication left open to supply Lee’s army.

OPERATIONS ON MAY 17-20, 1864 – FROM GENERAL HORACE PORTER, CAMPAIGNING WITH GRANT17

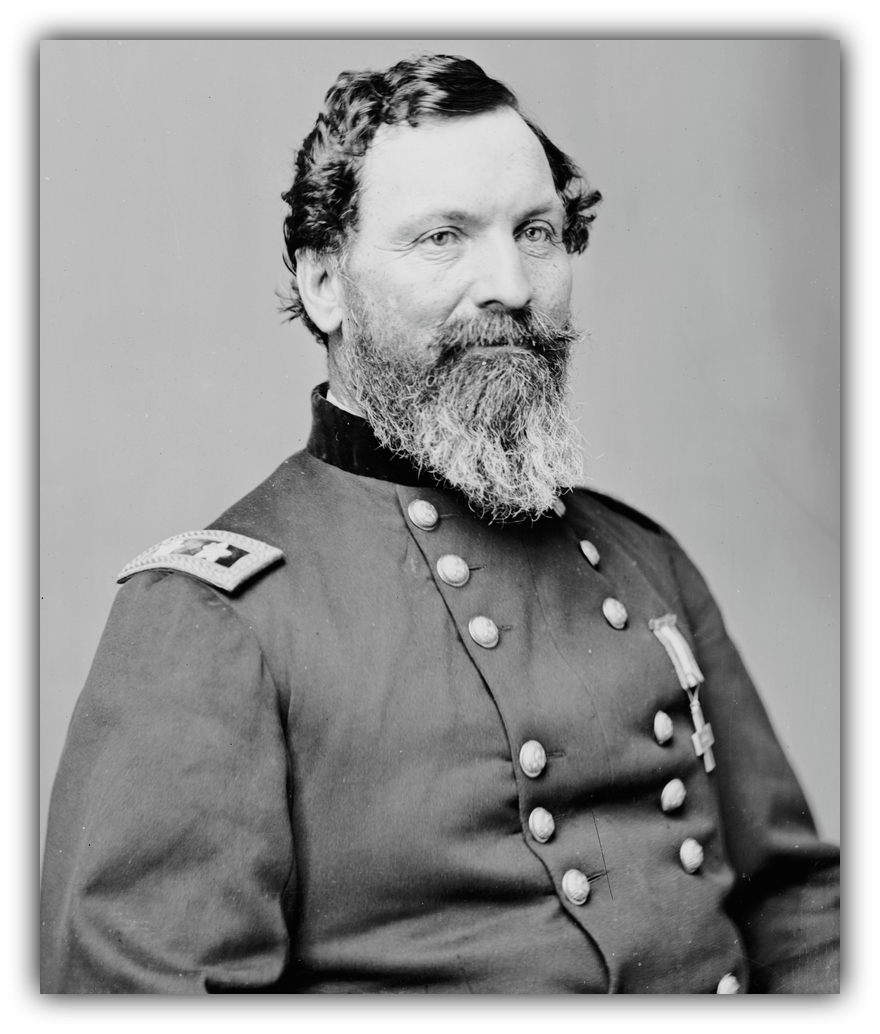

The weather looked a little brighter on May 17, but the roads were still so heavy that no movement was attempted. A few reinforcements were received at this time, mainly some heavy-artillery regiments from the defenses about Washington, who had been drilled to serve as infantry. On the 17th Brigadier-general R. O. Tyler arrived with a division of these troops, numbering, with the Corcoran Legion, which had also joined, nearly 8000 men. They were assigned to Hancock’s corps.

Headquarters were this day moved about a mile and a quarter to the southeast, to a point not far from Massaponax Church. We knew that the enemy had depleted the troops on his left in order to strengthen his right wing, and on the night of the 17th Hancock and Wright were ordered to assault Lee’s left the next morning, directing their attack against the second line he had taken up in rear of the “angle,” or, as some of the troops now called it, “Hell’s half-acre.” The enemy’s position, however, had been strengthened at this point more than it was supposed, and his new line of intrenchments had been given a very formidable character. Our attacking party found the ground completely swept by a heavy and destructive fire of musketry and artillery, but in spite of this the men moved gallantly forward and made desperate attempts to carry the works. It was soon demonstrated, however, that the movement could not result in success, and the troops were withdrawn.

When General Grant returned to his headquarters, greatly disappointed that the attack had not succeeded, he found dispatches from the other armies which were by no means likely to furnish consolation to him or to the officers about him. Sigel had been badly defeated at New Market and was in retreat; Butler had been driven from Drewry’s Bluff, though he still held possession of the road to Petersburg; and Banks had suffered defeat in Louisiana. The general was in no sense depressed by the information and received it in a philosophic spirit; but he was particularly annoyed by the dispatches from Sigel, for two hours before he had sent a message urging that officer to make his way to Staunton to stop supplies from being sent from there to Lee’s army. He immediately requested Halleck to have Sigel relieved and General Hunter put in command of his troops. General Canby was sent to supersede Banks; this was done by the authorities at Washington, and not upon General Grant’s suggestion, though the general thought well of Canby and made no objection.

In commenting briefly upon the bad news, General Grant said: “Lee will undoubtedly reinforce his army largely by bringing Beauregard’s troops from Richmond, now that Butler has been driven back, and will call in troops from the Valley since Sigel’s defeated forces have retreated to Cedar Creek. Hoke’s troops will be needed no longer in North Carolina, and I am prepared to see Lee’s forces in our front materially strengthened. I thought the other day that they must feel pretty blue in Richmond over the reports of our victories; but as they are in direct telegraphic communication with the points at which the fighting took place, they were no doubt at the same time aware of our defeats, of which we have not learned till to-day; so probably they did not feel as badly as we imagined.”

The general was not a man to waste any time over occurrences of the past; his first thoughts were always to redouble his efforts to take the initiative and overcome disaster by success. Now that his cooperating armies had failed him, he determined upon still bolder movements on the part of the troops under his immediate direction. As the weather was at this time more promising, his first act was to sit down at his field-desk and write an order providing for a general movement by the left flank toward Richmond, to begin the next night, May 19. He then sent to Washington asking the cooperation of the navy in changing our base of supplies to Port Royal on the Rappahannock.18

The fact that a change had been made in the position of our troops, and that Hancock’s corps had been withdrawn from our front and placed in rear of our center, evidently made Lee suspect that some movement was afoot, and he determined to send General Ewell’s corps to try to turn our right, and to put Early in readiness to cooperate in the movement if it should promise success.

In the afternoon of May 19, a little after five o’clock, I was taking a nap in my tent, to try to make up for the sleep lost the night before. Aides-de-camp in this campaign were usually engaged in riding back and forth during the night between headquarters and the different commands, communicating instructions for the next day, and had to catch their sleep in instalments. Hearing heavy firing in the direction of our rear, I put my head out of the tent, and seeing the general and staff standing near their horses, which had been saddled, I called for my horse and hastened to join them. Upon my inquiring what the matter was, the general said: “The enemy is detaching a large force to turn our right. I wish you would ride to the point of attack, and keep me posted as to the movement, and urge upon the commanders of the troops in that vicinity not only to check the advance of the enemy, but to take the offensive and destroy them if possible. You can say that Warren’s corps will be ordered to cooperate promptly.” General Meade had already sent urgent orders to his troops nearest the point threatened. I started up the Fredericksburg road, and saw a large force of infantry advancing, which proved to be the troops of Ewell’s corps who had crossed the Ny River. In the vicinity of the Harris house, about a mile east of the Ny, I found General Tyler’s division posted on the Fredericksburg road, with Kitching’s brigade on his left. By Meade’s direction Hancock had been ordered to send a division to move at double-quick to Tyler’s support, and Warren’s Maryland brigade arrived on the ground later. The enemy had made a vigorous attack on Tyler and Kitching, and the contest was raging fiercely along their lines. I rode up to Tyler, who was an old army friend, found him making every possible disposition to check the enemy’s advance, and called out to him: “Tyler, you are in luck to-day. It isn’t everyone who has a chance to make such a debut on joining an army. You are certain to knock a brevet out of this day’s fight.” He said: “As you see, my men are raw hands at this sort of work, but they are behaving like veterans.”