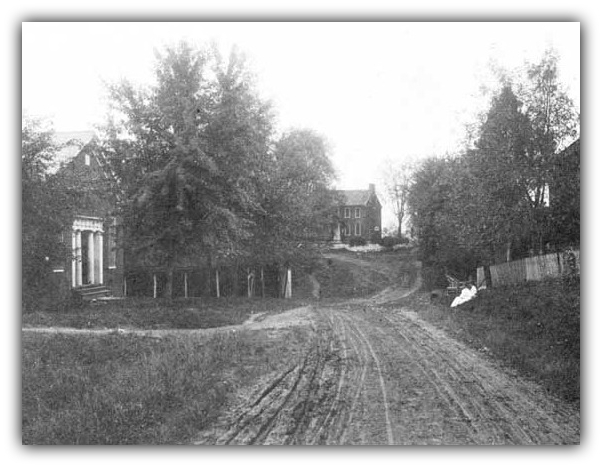

Waterford Baptist Church, High & Church Streets, Waterford, Loudoun County, VA

Mairi and I had a strong fascination with Waterford, Virginia. As Civil War historians we knew that it was a town of Union sympathies, however, upon our first visit to the town we were enthralled by its preserved 19th architecture and aura, and by its fascinating history, especially during the Civil War.

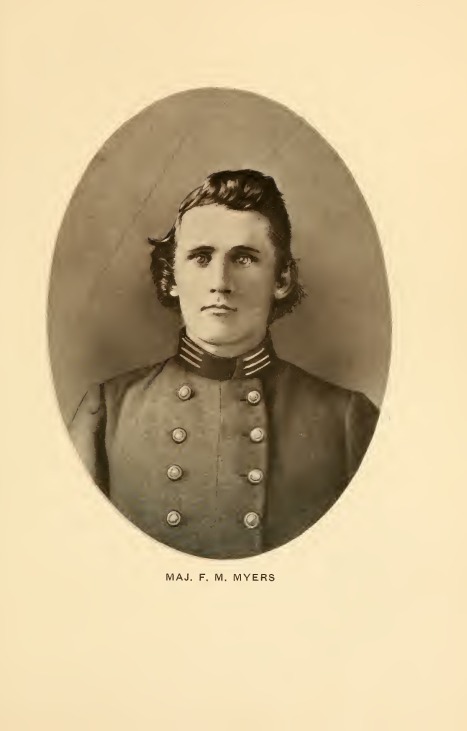

In this recount of that history, we have chosen the writings of two first-hand accounts. The first was written by Briscoe Goodhart, Company A, Independent Loudoun Rangers, who actually was in the church when the skirmish was being fought. The below excerpt is from his: History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers: U.S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts) 1862-65. The second account is by Frank M. Myers Captain, 35th Virginia Cavalry. His work is a comprehensive account of the skirmish with an amazing amount of detail from the Confederate perspective. The below excerpt is from his book The Comanches A History of White’s Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Laurel Brig., Hampton Div., A.N.V., C.S.A.

In between these two accounts is a short account of Maggie Grover, who through her courageous efforts might have actually saved the town in Waterford in March of 1862.

Lastly, there is a New York Times article reporting this action dated September 1, 1862, with the news article Thursday August 28, 1862.

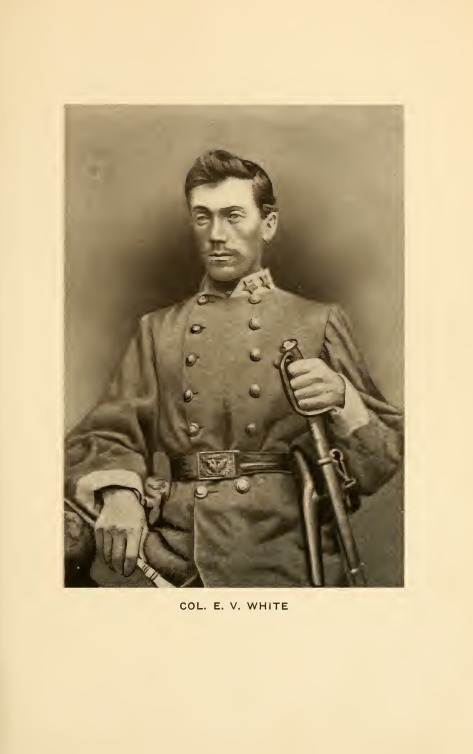

The Fight at Waterford was a small skirmish during the American Civil War that took place in Waterford, Virginia on August 27, 1862 between the local partisan cavalry units of White’s Comanches led by Lieutenant Colonel Elijah V. White, fighting for the Confederates, and the Independent Loudoun Rangers, led by Captain Samuel C. Means, fighting for the Union. The Rebels surprised and routed the newly formed Loudoun Rangers in their camp at Waterford, capturing nearly the whole unit before subsequently paroling them, thus resulting in a Confederate victory. The action was the first significant partisan fighting in Loudoun County.

History of the Independent Loudoun Virginia Rangers: U.S. Vol. Cav. (Scouts) 1862-65

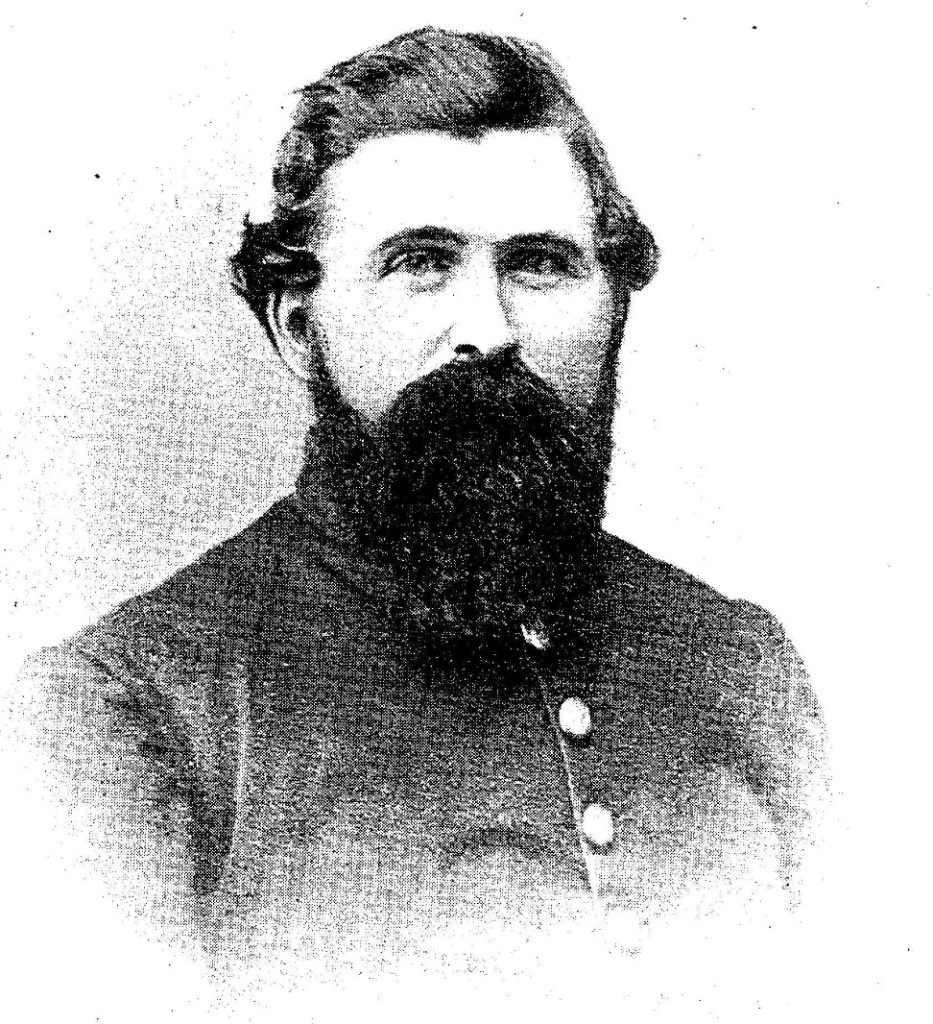

by Briscoe Goodhart, Company A, Independent Loudoun Rangers

Back row from left: John Densmore, George Michael Wilt, Robert W. Hough, John Davis, John Lenhart, Daniel Harper, Thomas Harrison. Front row from left: Charles W. Virts, Briscoe Goodhart, John Hickman, Joseph T. Divine, George Davis, Samuel Tritapoe, Isaac Hough.

Chapter III.

Samuel C. Means goes to Maryland—Gets a Commission to

RAISE A Company of Cavalry—Recruiting at Lovettsville ETC.

ELECTION OF OFFICERS — The WATERFORD Fight.

Samuel C. Means, a prominent citizen and a successful businessman, owned and operated a splendid flour mill at Waterford, the largest in the county. He and his brother (Noble B. Means) owned and conducted a large mercantile business at Point of Rocks, Md., and in addition to this was station agent of the B. & O. R. R. at the latter place. He wagoned the product of his mill to Point of Rocks, and shipped it thence by rail, to Baltimore market. There were very few men in Loudoun County doing a better business than Mr. Means. He went from his mill to his store daily, attending to his business as manufacturer, merchant, and railroad agent. The Confederates had repeatedly made very complimentary offers to Mr. Means, to enlist his sympathy for their cause, but without success. They next tried a system of coercion, with the same results. Finally, he was notified that he must support the Confederacy or else he would be compelled to leave the State, and if he left the State, it would be presumed he was an enemy to the Confederacy, and his property would be confiscated. To all their coaxing and threatening he emphatically said: “No, gentlemen; you are waging a cruel and malicious war, without the slightest pretext, or excuse, upon the best government that ever existed. No, gentlemen, I will never take up arms against the United States; I will not be guilty of such disloyalty to my country.” Mr. Means was a passionate and a positive man, and when presenting a statement would often grow emphatic, as was the case in this instance. The Confederates now determined to carry out their threats and took a quantity of his flour for which they promised pay, but never paid. They also took some of his stock. The crisis had come. Mr. Means went to Maryland about July 1, 1861, leaving his family behind. The Confederates took all his property that remained, consisting, in part, of 28 head of horses, 2 wagons, 42 head of hogs, large quantities of flour, meal, etc. It should not be forgotten that it was no small sacrifice on his part, and also let it be well understood, it was for patriotism, for a lofty principle, that this self-sacrifice was made. When Mr. Means left home, he had no intention of going into the army, he so stated to his wife, and so wrote her after his arrival in Maryland. He had a brother in the rebel army and did not wish to appear in a personal attitude on that account. After the first battle of Bull Run, where the Union army met with defeat, and the President called for 300,000 troops, the question of duty presented itself so forcibly that he could not resist. He broke the news first to his wife by letter, which almost broke her heart. Mr. Means made Point of Rocks his headquarters, attending to his private affairs.

It had been reported, during the fall of 1861, that Mr. Means had crossed the Potomac into Virginia, in disguise, and visited his home in Waterford, and had been concealed in his house for several days at a time. Capt. William Meade’s company of the Loudoun Cavalry (Confederate), encamped in the latter village, received special instructions to capture Mr. Means at all hazards. A picket was stationed on Main Street, in full view of the Means residence, with orders to rigidly guard it. On October 18, at twelve o’clock, midnight, as there was noticed a dim light going from room to room, in the Means house, the officer of the guard deemed it of sufficient importance to call Capt. Meade—and there was also noticed a man approach the Means residence and enter from the back door. This was abundant evidence to Capt. Meade that Mr. Means was at home, and that the time to capture him had arrived; so with a squad of men he immediately surrounded the Means residence, and when all was ready to enter and make the capture, suddenly the back door opened and a person darted out through the garden in a somewhat hurried manner. Capt. Meade and Lieut. Len Giddings, with cocked revolver in each hand, rushed like a Kansas cyclone upon this person, yelling, “Surrender! Surrender! Sam Means, we have got you this time.” By the dashing and ferocious bravery of these two heroes of many battles, the person was captured, slick and clean, and without a shot from either side. The appetite for gore of these two battle-scarred veterans was abundantly satisfied. Capt. Means was not at home. The person thus captured was, it appears, a female nurse attending upon a member of Mrs. Means’ family, who was busy making arrangements to entertain a little stranger who had just come to town.

Capt. Meade well earned the title of “Granny Meade.”

The 28th Pennsylvania Infantry, in command of Colonel, afterwards Gen., John W Geary, lay at Point of Rocks, Md., and the 6th Independent Battery, New York Artillery, lay at Brunswick. Mr. Means spent much of his time with these two commands. Col. Geary was formerly a large real estate owner of Loudoun, having owned a large interest in the Catoctin Furnace tract, opposite Point of Rocks.

These commands made repeated raids into Loudoun during the fall and winter for the purpose of capturing bands of rebels that were scouting in the county and annoying Union people. In December the 6th Independent New York Battery sent over into Virginia a raiding party of about twenty-five men, who crossed at Brunswick about 7 o’clock p.m., went by Lovettsville, capturing two rebels there, and, having traveled eastward, arrived opposite Point of Rocks about daylight, where they surprised a rebel picket post, capturing four and killing one, by the name of Orrison. While Mr. Means probably had nothing to do with these raids (Mrs. Means received a letter from her husband who was in Baltimore the night of the raid), the Confederates accused him of their origin, and charged that the damage inflicted on the rebels was directly traceable to his hands. Consequently, a reward of $5,000 was offered bv the Confederate authorities in Richmond for the head of Samuel C. Means, whom they characterized as the renegade, Sam. Means. The epithet renegade was in exceeding bad taste. It should be remembered that Mr. Means was simply one of a majority that refused to be defrauded out of his rights by the minority. A copy of the paper that contained the advertisement of a reward was sent to Mrs. Means from Richmond.

During January, 1862, Mr. Means received a letter from the Hon. Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, requesting him to call at the War Department. On his arrival the Secretary offered him a commission, with the request that he would raise a command for the Union army. He informed the Hon. Secretary he would be pleased to accept the honor but at present he could not, but just as soon as he could adjust his private affairs he intended to offer his services in defense of the Union. In the meantime, he transferred his business to his brother. During the month of March there was a forward move of the army all along the Potomac from Washington to Cumberland. Col. Geary crossed the Potomac with his regiment, the 28th Pennsylvania, at Harper’s Ferry, with Mr. Means as guide, and took possession of Lovettsville and Waterford.

This was the first time Mr. Means had returned to his home since he left it in July previous. He continued as guide to the army until May, when he returned to Washington and obtained a commission as captain, with instructions to recruit a company of cavalry to be known as the Independent Loudoun Guards. Capt. Means was mustered into the United States service as captain, by Col. Dixon S. Miles, at Harper’s Ferry, June 20, 1862. At the muster the name Rangers was substituted for Guards. Headquarters were immediately established at Waterford, where recruiting was begun. The first name enrolled after that of Capt. Means was James A. Cox, of Hamilton, and that was followed closely by Charles F. Anderson, Flemon B. Anderson, John S. Densmore, Jacob E. Boryer, Armstead Everhart, Luther W Slater, Daniel M. Keyes, James H. Corbin, David E. B. Hough, Temple Fouch, John W. Forsythe, Joseph T. Cantwell, Thomas J. McCutcheon, Daniel J. Harper, Robert S. Harper, Henry C. Fouch, James W. Gregg and Milton S. Gregg, W. H. Angelow, Charles F. Atwell, J. W and S. Shackelford, Michael Mullen, James T. Wright, Samuel C. Hough, William Hough, Henry C. Hough. About July 1 the company moved camp to the Valley church, near Goresville, where about one dozen recruits were enrolled.

Joseph Waters was accidentally wounded by the discharge of a carbine while encamped here. This being our first man wounded in the company, the boys gathered around Joe uttering sympathetic bravos.

Secretary Stanton had given Capt. Means instructions to mount the company on horses that belonged to parties that had gone into the rebel army. While encamped at the church Capt. Means learned of a stranger at George Smith’s residence, near Waterford, sick and apparently stranded. A detail was ordered, with instructions to bring this stranger to camp. He seemed to be much pleased at the change, but being an entire stranger, he was sent to Col. Miles at Harper’s Ferry, where he was questioned at some length, when the oath of allegiance was administered to him. He then returned to our camp and offered himself as a recruit, giving the name of Charles A. Webster. He was reticent as to his past history, but had evidently seen service before he came to us, being exceptionally well drilled in the cavalry tactics; was an excellent specimen of manhood, about five feet ten inches high, weighing about one hundred and eighty pounds, rather light complexioned, and about 25 years old; very quick and active, a splendid shot, and wielded a sabre with great skill and effect.

Up to this time there was not a man in the company that understood the first principles of drilling; so Webster proved to be just the kind of a man that was needed, and he was immediately appointed our drill master.

It having been learned that some parties were engaged in forwarding rebel supplies from Baltimore and crossing the Potomac near Leesburg, a detail was made, with instructions to arrest those parties if possible. The squad started early in the morning, about 7th of July, crossing the Potomac at Edward’s Ferry, where several parties were attempting to cross into Virginia with supplies for the Confederate army, consisting of arms, ammunition, clothing, etc. The parties thus engaged were arrested, and with the goods loaded on a canal boat and taken to Harper’s Ferry and turned over to Col. Miles’ command. The squad returned to the Valley church that evening, and having traveled about thirty-five miles that day, both men and horses were entirely exhausted.

About July 10 the company moved to Lovettsville and camped in the German Reformed church. This proved to be a very popular camp, being situated in the center of the German settlement, amongst friends. About twenty-five recruits enrolled their names here.

The company now numbered about fifty men, and was entitled to elect its officers. Capt. Means having been appointed captain, an election of officers was held, with the following result: 1st Lieut., Luther W Slater; 2d Lieut., Daniel M. Keyes; Quartermaster, Charles F. Anderson; First Sergt., James A. Cox.

There were no other officers elected, or appointed, on this occasion. Charles E. Evard, of Leesburg, had been with the company for several weeks and was a modest candidate for first lieutenant. After this election he seemed to take little interest in the command, and finally left it entirely after the Waterford fight.

About the 1st of August the company moved back to Waterford and camped in the Baptist church. The company continued to grow, and under the efficient drillmaster, Webster, began to obtain proficiency in the manual of arms. The company was now engaged in active scouting and succeeded in mounting all recruits on captured horses.

The Union army, under Gen. McClellan, had been compelled to retire from before Richmond, and the rebel army, somewhat elated over its dearly purchased temporary success, was moving northward. Quite a number had already returned to Loudoun and adjoining counties for the purpose of recruiting. Capt. Richard Simpson, of the 8th Va. Reg. Inf., with a detachment, was reported to be at Mount Gilead recruiting for that regiment. Capt. Cole, with a detachment of the 1st Md.. P H. B. Cav., came down from Harper’s Ferry on a contemplated raid to Middleburg and Upperville. Capt. Means and about thirty men joined the raid and suggested the route via Mount Gilead. The command left Waterford late in the afternoon and camped for the night south of Clark’s Gap. By making an early start an advance guard, consisting of Lieut. D. M. Keyes, Charles A. Webster, James H. Beatty, M.S. Gregg, and perhaps two others, was hurried off in the direction of Mount Gilead and arrived at Capt. Simpson’s rendezvous about 6 o’clock a.m. The building was surrounded, but the birds had flown. Lieut. Keyes ordered his men to proceed at once to Capt. Simpson’s residence, located a half mile distant in a hollow. As they approached the house Capt. Simpson made his exit from the back door and ran across a field towards the timber. He was commanded to halt, but kept running. Keyes, Webster, and Beatty fired several shots at him, one of which struck him in the leg, causing him to fall on his hands and knees, but he immediately jumped up and continued running towards the woods. Keyes gave chase across the field, while Webster, Beatty, Gregg, and others went around to head Simpson off at the woods. In the chase Keyes had emptied his revolver at Simpson, who had two revolvers, one of which contained several loads; and as Webster rode up he fired at Simpson, the ball taking effect in the body, bringing him to his knees, in which position he raised his revolver to shoot Webster. The latter, being very quick, wrenched one of Simpson’s revolvers from his hand and with this weapon fired again, striking him, Simpson, in the neck, and from the effect of these wounds he soon died. Simpson was brave to recklessness. Valuable Confederate papers were found on his person. Webster has been severely criticized, and perhaps to some extent justly, for the seemingly hasty methods used on this occasion; but Capt. Simpson had positively refused all demands made on him to surrender.

The advance guard waited for the column to come up, when the command proceeded via Aldie to Middleburg, where a squad of rebels was encountered and two captured.

The column moved on to Upperville where we arrived soon after daybreak. This was a secession stronghold. The women were even more pronounced in their views than the men, and grew eloquent in their denunciation of the Yankees.

Capt. Means and Capt. Cole rode through the streets of the village, calling out to the citizens to prepare breakfast. The officers entered the same house, but much to their surprise no breakfast was visible. Capt. Means asked for a cup to get a drink of milk. No heed was given to this request. Finally, Ed. Jacobs discovered some fine glassware on the sideboard and proceeded to pour out the milk for the temporary guests. This was more than the landlady could endure. In her rage she exclaimed: “Why, the very idea of a Yankee drinking out of a cut glass!”

The command moved by way of Bloomfield, Purcellville, and Hamilton, back to camp at Waterford.

The entire Confederate army of Northern Virginia was now marching northward, threatening an invasion of Maryland. Our little camp at Waterford was somewhat exposed, we being the only Federal soldiers in this section of the State. Reports of the approach of the enemy were whispered around camp, but as the same news had been circulated for several weeks previous no particular importance was attached to the rumor. Capt. Means had received private information that evening, August 26, which led him to believe that an attack that night was possible, although not probable.

The total strength of the company at this period was about fifty men, but a portion of that number were absent on a raid. There were six public roads leading into the village, and a picket of four men was posted on each, taking just twenty-four men, leaving about twenty men in camp in the church, the latter being largely recruits, having quite recently joined fully half of the camp had been enrolled less than thirty days.

Capt. Means was vigilant that night, endeavoring to learn of the accuracy of flying rumors, and visited the church as late as twelve o’clock midnight. When all seemed quiet he retired with his family, who lived in Waterford.

Lieut. Luther W. Slater had been absent at his home for several days, sick, and had returned to camp that evening, partially recovered. Owing to the small number of men in camp First Sergeant Cox was having some difficulty in mounting the guard, and Lieut. Slater, who was a very popular officer, saw the embarrassment of the sergeant and cast himself in the breach by assuming double duty, acting as corporal of the guard as well as officer of the day.

A few minutes before three o’clock a. m., August 27, the enemy, consisting of Maj. E. V. White’s 35th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, Ewell’s Brigade, by being dismounted, and piloted by citizens and crossing fields, evaded our pickets and succeeded in reaching our camp unobserved.

The first apprehension we had of the approach of the enemy was an unusual noise, caused by the enemy, ostensibly for the purpose of drawing our men out of the church. The men rushed out in the front yard, where Lieut. Slater hastily formed them in line. A body of men could barely be recognized on the bank in front and on each side of the Virt’s house and in the edge of the green corn. Lieut. Slater’s clear voice rang out on the early morning air in quick utterance, ” Halt! Who comes there?” and in answer received a terrific volley from the carbines of the enemy, which our men gallantly returned, notwithstanding over half had been wounded.

The rebels now took position behind buildings and in the green corn, and the Rangers fell back into the church. Lieut. Slater, although severely wounded, retained command until compelled by the loss of blood to relinquish that charge to Drillmaster Charles A. Webster, who continued the fight to its final termination, in a way that shed luster on his career as a brave and meritorious officer.

The rebels continued firing through the windows and the porch or vestibule of the church, a lath and plastered partition extending across the entire front. The bullets poured through this barrier as they would through paper. The Rangers returned the fire as vigorously as circumstances would permit. After continuing the firing for about thirty minutes Maj. White sent in a flag of truce (by Mrs. Virts) demanding a surrender, which was refused by Webster in rather emphatic language, that is not often heard in a church. The fight was continued, perhaps one hour longer, when the second flag of truce was sent in, making the same demand and sharing the same fate as the first, notwithstanding that one-half of the little band had been wounded and lay around in the church pews weltering in their blood, making the place look more like a slaughter pen than a house of worship.

Our ammunition was almost exhausted, yet we hoped against hope that possibly assistance might reach us. The cry of the wounded for “Water! Water! Water!” when there was no water to be had, will never be forgotten. The firing was kept up perhaps one hour longer, to about 6.30 or 7 o’clock, when the third flag of truce was sent in, making the same demands as the first and second. At this time our ammunition was entirely exhausted, and as there was no possible way of replenishing that all-important article, Webster consulted Lieut. Slater as to what was best to do under the very precarious and unfortunate circumstances. Lieut. Slater was lying in a pew on the north side of the church, being very weak from the loss of blood, which was still ebbing away, his underclothes being entirely saturated, and from the wound in his right temple his face was entirely covered with blood. But possessing great physical endurance he was able to dictate a reply to Maj. White’s demand for a capitulation, which was conditional. The conditions as demanded by Slater and Webster were that all should be paroled and released on the spot; the officers to retain their side arms.

These terms were immediately accepted by Maj. White.

It was exceedingly fortunate for the Rangers at this juncture that the enemy made this third demand for a surrender, as it was impossible to have held out any longer; and if he had only known it, he could have marched in and taken all prisoners and marched them off to Richmond. Maj. White asked that Webster meet him in the center of the street, under flag of truce, to arrange preliminaries. Webster drew his sword, and placing a pocket-handkerchief, belonging to John P. Hickman, on the point proceeded to the street to meet his antagonist. After exchanging greetings. White asked that Webster form his men in line in front of the church and surrender their arms, when all should be paroled and released. After all those that formed in line were paroled Maj. White went in the church, where those who were severely wounded were paroled. On approaching Lieut. Slater, he remarked: ” I am sorry to see you so dangerously wounded, Lieutenant.”

Before the capitulation had taken place Maj. White sent a detachment down town, where our new arms and ammunition were stored, and got that which we were so badly in need of at the church. After all had been paroled the enemy took the captured property and two prisoners, J. H. Corbin and Joseph Waters, and immediately left town, going south. Corbin and Waters were captured outside of the church, and not included in the terms of capitulation.

| The casualties of this engagement were: |

| Killed: |

| Charles Dixon |

| Wounded: |

| Lieut. Slater, five wounds—temple, shoulder, arm, breast, hand; a carbine ball passed through the top of his hat, but did no damage to his person. |

| Edward N. Jacobs, severely, ball passing through thigh bone. |

| James W Gregg, in both arms. |

| D. M. Keyes, in neck. |

| Henry C. Hough, in knee. |

| James A. Cox, in arm. |

| Robert W Hough, in hand. |

| Charles A. Webster, in side. |

| Colored man, company cook, in neck. |

Henry Dixon was taken to the residence of Mr. Chalmers, where he was very tenderly cared for until death relieved him of his sufferings.

Lieut. Slater was taken to the residence of Mr. Densmore, where he remained one week; from there he was removed to the residence of Mr. George Alders, “Scotland,” remaining there three weeks, when about ten of his neighbors came and fastened a pole on each side of his rocking chair, in which position they carried him to his father’s residence, near Taylortown. He was kept there about two weeks, and removed to Gettysburg, Pa., where he remained until his wounds healed sufficiently to allow him to travel.

While at Gettysburg he was again wounded, but by no means painfully. While smarting under the sting of “rebel bullets” he fell a victim to “Cupid’s darts.” The “Guardian Angel” that so often and so tenderly dressed his wounds and administered to his wants afterwards became Mrs. Slater.

Edward N. Jacobs was taken to the residence of John B. Button.

The others, whose wounds were painful, but not such as to prevent them from traveling, were taken to their various homes. The following is the list of prisoners taken and paroled:

| 1st Lieutenant L.W. Slater | John W. Forsythe |

| Charles A. Webster | T.W. Franklin |

| James A. Cox | Samuel Fry |

| Edward N. Jacobs | Joseph Fry |

| John P. Hickman | R.W. Hough |

| Henry C. Hough | George W. Hough |

| James W. Gregg | S.J. Harper |

| Charles H. Snoots | Charles L. Spring |

| Samuel E. Tritapoe |

After the first volley 2d Lieut. D. M. Keyes, Joseph T. Divine, Jacob E. Boryer, and Charles White succeeded in making their escape by going down in the basement and jumping out of the rear window on the south side of the church.

The venerable Dr. Bond very kindly and very tenderly attended all the wounded.

The author, who was in the church at the time, was not paroled. He had enlisted three days previously, but was so short legged that a uniform could not be found small enough; but he had drawn one and taken it down town to Mrs. Leggett’s to have it made smaller, and was wearing a suit of citizens clothes, and was not taken for a soldier. After the rest had been paroled, he was recognized by Lieut. R. C. Marlow, the latter probably supposing he was paroled.

| The casualties on the Confederate side, so far as known, were: |

| Killed.—Lieut. Brooke Hayes. |

| Peter J. Kabrich, mortally wounded, died a few days afterwards. |

Those that were able to be moved were taken South; their number and names have never been learned.

While the fight was in progress Mr. Kabrich ventured from behind the house and undertook to get one of the Rangers’ horses that stood near the well. While he was untying the animal Webster raised his carbine and fired and Kabrich fell, mortally wounded.

Many of White’s men and the Rangers had been schoolmates, and in some instances reared around the same fireside; one brother following the Confederate banner with a pitiable and delusive blindness, while the other brother stood firm in his allegiance to the Stars and Stripes.

In this fight brothers met. After the Rangers had been paroled Wm. Snoots, of White’s command, wanted to shoot his brother Charles, who belonged to the Rangers, but was fittingly rebuked by his officers for such an unsoldierly and unbrotherly desire. Charles, who had been deprived of his arms, keenly felt the advantage his brother wanted to take, and modestly suggested to brother Bill that if he would unbuckle his arms and lay them aside he, Charles, would wipe up the earth with the cowardly cur in less than two minutes.

The official records fail to show any reports of this engagement from either side, the only mention made is the following telegram from General Wool to Secretary Stanton:

“Harper’s Ferry, Va., August 27, 1862.

” Cole’s Maryland Cavalry returned from Waterford. The enemy, under Capt. White, by crossing fields and avoiding the pickets, attacked twenty-three of Means’ men in a church at daybreak this morning, who fought as long as they had ammunition. Two privates killed, 1st and 2d lieutenants and six privates wounded, fifteen surrendered on parole, two engaged in killing Mr. Jones carried off to Richmond to be held as hostages: also, thirty horses and all the arms of the company except those on picket. The enemy lost six killed and nine wounded.

“John E. Wool, “Maj. Gen., Commanding”

J. H. Corbin and Joseph Waters were taken to Culpeper Court House, where the latter was paroled, Corbin was placed in prison, charged with killing a Mr. Jones, which occurred previous to Corbin’ s enlistment; the latter remained in irons about ten days, when a loyal citizen of that place assisted him in making his escape.

The Confederates, under command of Maj. White, with White’s command, and Capt. Randolph, of the Black Horse Cavalry (4th Va.), and Capt. Gallaher, of Ashby’s Cavalry, the latter as scouts, the entire cavalcade numbering perhaps two hundred, left the North Fork of the Rappahannock River August 24, and marched through Fauquier County, entering Loudoun near Middleburg, taking the Mountain Road, and marched direct to Waterford, arriving about 2 o’clock a.m., August 27, dismounting near Robert Hollingsworth’s barn, where the horses were left, and marched direct to the church and. made the attack. The command was piloted by about a half dozen citizens—Henry Ball, J. Simpson, and others, who lived in Loudoun.

A few days before the fight there came to our camp at Waterford a Mr. Robertson and joined the company; a very quiet fellow, but apparently had his eyes open. An entire stranger to all, the only person he seemed to cultivate the acquaintance of was Joseph T. Divine, whom he asked to accompany him to the residence of Gen. Robert L. Wright, near Wheatland. He remained around camp until about the time of the fight, when he disappeared forever from the company.

It is believed that Mr. Robertson was a Confederate spy and belonged to the command of Capt. Gallaher, who accompanied White on this raid, and that he afterwards joined White’s company, as a man by that name joined that command in 1862.

The “Fearless Act” of Maggie Grove that Saved Waterford

Colonel John W. Geary’s 28th Pennsylvania Infantry intended a direct march on Leesburg, but late intelligence prompted a detour. On the night of 6-7 March 1862, as Captains White and Graves1 prepared to leave Waterford, Maggie Gover overheard the cavalrymen threaten to return and burn “the cursed Quaker settlement” before it fell into Federal hands. Her husband, shopkeeper Sam Gover, had fled to Washington the previous summer, and she was now living next to their boarded-up store with her mother-in-law, Miriam Gover. Determined to get help and “in the absence of any man who was willing to perform the perilous duty,” Maggie tried to borrow a horse from a neighbor to ride to Geary’s camp in Lovettsville. When the timid Quaker refused her request, she had a servant steal the mount. After a hazardous eight-mile ride past Rebel pickets in the dark, Maggie arrived at the Union headquarters and briefly paused to salute the “good old flag,” which she had not seen for nearly a year. Colonel Geary, on hearing her story, including details about the Confederates’ evacuation plans, complimented Maggie for her “fearless act” and agreed to divert his forces to save her village.2

The Comanches: a history of White’s battalion, Virginia cavalry, Laurel brig., Hampton div., A.N.V., C.S.A. – Frank M. Myers Capt., 35th Va. Cavalry.3

Pope made a stand on the Rappahannock, and while waiting for the Southern army to drive him back again Capt. White4 perfected his plans for the Loudoun expedition, and at Warrenton White Sulphur Springs got Gen. Ewell’s sanction to it. When, on the 25th of August, “Stonewall” left the main army and started on his flank movement to Manassas, White marched with him, crossing the river opposite Orleans, after which he made as fast time as possible in order to gain the front of Jackson’s corps, which he succeeded in doing at Salem. Just as his company passed the last regiment the men, who had halted to rest, called out, “you wouldn’t have caught up with us if the Colonel’s horse hadn’t given out.” At sunset the raiding party, having cleared all the troops, marched to the Bull Run Mountain, which point they reached about daylight, and where they proposed to lie over until night of the 26th. During the day the true-hearted citizens of the neighborhood brought in plenty to eat, and some of them spent a great part of the day in the camp, among them Mr. Ball, Mr. Simpson, Mr. Wynkoop and others.

When the dark came down over the mountain the Captain formed his men, consisting of about twenty of his own company, with Lieuts. Myers and Marlow, about twenty of Capt. Randolph’s company, with Capt. R. and Lieuts. Redmond and Mount, and half a dozen of Gen. Jackson’s scouts under that splendid soldier Dr. Gallaher. After the line was formed White made a short speech, telling his command that his object in the expedition was to whip Means’ men,5 and that no matter how much force they had he intended to do it; that he knew where they were, and if the expedition failed it would be the fault of his own men; closing by saying with King Henry, if any man among them had no stomach for the fight upon such terms he was now at liberty to return. The little force, augmented by the addition of Messrs. Henry Ball and J. Simpson, now took up the line of march for Waterford, passing along the mountain all the way, and arriving at Franklin’s Mill an hour before daylight, when a halt was ordered and scouts sent out to ascertain if any changes had been made in the disposition of Means’ command.

While lying here a party of eight was heard passing the road from Leesburg, who, from their conversation, were rightly judged to have been scouting all night to learn if there was any movements of the Southern army to the northward, and their words proved that they were perfectly satisfied and felt entirely secure, for among other things their leader was heard to declare, as they watered their horses within ten feet of one of White’s scouts, that “there wasn’t a rebel soldier north of the Rappahannock.”

As soon as this party passed beyond hearing, White moved his people to Mr. Hollingsworth’s barn-yard, where about twenty of them were dismounted, under command of Capt. Randolph, and ordered to march to the enemy’s quarters, which were in the Baptist meeting-house, about one hundred yards distant, with instructions not to fire until they entered the house, or, in case the enemy was outside, to get into the yard with them before firing, and then to rush upon them and go with them into the house. The Captain held the remainder of his men mounted, and rode to the brow of the hill in the road by Hollingsworth’s gate to wait for the movement of Randolph to drive the Yankee boys from their quarters, when the cavalry would dash down and capture them.

Dawn was just beginning to turn the black of night to the gray of early morn when the movement commenced, and on Capt. Randolph’s party getting near enough to see, they discovered Means’ whole force standing in the yard listening to the report of their scouting party, which had just come in, and though they looked wonderingly at the infantry advance of White’s army, not one of them said a word; but in spite of his orders, which could have been executed with perfect safety, Randolph ordered his men to fire as soon as they reached the corner of the palings around the yard, which caused the Yankees to break and rush into the house in great confusion, having their commander, Lieut. Slater, badly wounded; and now, instead of following them, as his orders required, Randolph retired to Virts’ house, just opposite; but the gallant Gallaher, with Jack Dove and a few others, tried to execute the order, and while Gallaher, springing into one window, fired his revolver bullets among the demoralized “boys in blue,” the others poured their buckshot in at the other windows.

As soon as the firing commenced White brought his cavalry down the road at a gallop, and halting long enough to fire a round or two at the side windows of the meeting-house, discovered quite a number of Means’ men leaping from the windows and making the fastest kind of time across the lots below the house, so calling on his boys to follow the Captain made a dash down into town, but only succeeded in capturing two of the fugitives. From here some of the men galloped down to Means’ house in the hope of getting that gentleman, but he was by that time “over the hills and far away,” according to his custom when rebel bullets were on the wing.

Returning to the meeting-house, in broad daylight, White found his infantry laying close siege to it, and standing in the vestibule was the daring Webster, who had assumed command of the Yankees, and who, seeing White’s mounted men riding up, supposed them to be a reinforcement for himself, and began firing upon Randolph’s men at Virt’s house, calling, as he did so, for his own men to come out and fight. A few pistol balls near him showed him his mistake, when he deliberately turned on the cavalry and emptied his revolver at them, after which he stepped back into the house and commenced to barricade the doors. White’s whole force now dismounted and opened a brisk fire at the windows, which was returned by Webster, Cox, and a few others, whom Webster succeeded in bringing from under the benches long enough to take a shot; but pretty soon it was discovered that ammunition was running short in White’s ranks, and knowing the impossibility of taking the place by assault now, the Captain prepared to withdraw his people, but on reaching the horses of the dismounted men he resolved upon shooting the horses of the Yankees, which had been tied in the yard during the fight, and presented to the gaze of the now baffled Confederates a prize well worth fighting for, composed as they were of the very best horses of Loudoun, a land always noted for fine ones, and equipped in the most superb style of the U. S. A. Previous to this, however, an attempt had been made to negotiate a surrender by sending Mrs. Virts, under a truce, to make the proposition, but on her second mission the enemy informed her that if she came again they would shoot her; and now nothing remained but to get away in safety, which could only be done by depriving the Yankees of the means of following; and collecting the remaining cartridges a detail was sent to kill the horses; but while this party was getting in position around Virts’ house it appears that the enemy were so badly frightened they were trying to force their commander to make terms, and a few shots from Ben. Conrad and Ross Douglass at some Yankees they saw by a window, precipitated matters and brought Webster out with a flag of truce. He demanded the usual terms in such cases, viz: his men to be released on parole, their private property respected, and officers to retain their side arms; which White immediately granted, and the affair was concluded as soon as possible, the victors getting fifty-six horses, saddles and bridles, about one hundred fine revolvers and as many carbines, with a vast quantity of plunder which they were unable to carry off; and paroling twenty-eight prisoners, which, with the two previously captured, made thirty in all.

White lost Brook Hays, killed, and Corporal Peter J. Kabrich, mortally wounded; both gallant soldiers as ever drew a sabre. A few others were slightly injured. The enemy lost about seven or eight in killed and wounded.

The scene at the surrender, when Means’ men, after being formed in line, laid down their arms, was a curious one. Many of them were old friends, and had been schoolboys with some of White’s men; and in one instance, brothers met: one, Wm. Snoots, being a Sergeant in White’s company, and the other, Charles, a member of Means’ command. Rebel and Yankee had swallowed up the feeling of brotherhood, or rather, that feeling had intensified the bitterness and hatred with which enemies in the hour of conflict regard each other; and the rebel would have certainly shot his Yankee brother, even after the surrender, but for the interference of one of the officers. As soon as possible, after getting everything in movable shape, and arranging for the care of Kabrich, who was too badly hurt to be moved, and for the burial of Hays, the raiders turned their faces towards the South again, expecting to rejoin Gen. Jackson that night. At the point where the line of march diverged from the Leesburg road, Capt. White left Lieut. Myers in charge of the column, and taking with him a small detail, galloped into Leesburg, where he created quite a commotion, causing a few Yankee soldiers there to depart in the shortest time imaginable, and making the Southern people of that extremely Southern town almost wild with joy.

They had been under the galling rule of Yankeedom, as administered by such as Geary, until simple endurance had almost culminated in despair, and the advent of White, so unexpectedly, among them, was hailed as an omen that their day was beginning to dawn; and consequently, in their freshly blooming hope, they petted and lionized to their heart’s content the little band of boys in gray who came to assure them that soon they would be free from the rule of their hated tyrants.

The two parties united about sunset, at Aldie, where all partook of an excellent supper at Mr. Henry Ball’s, and where the Captain again met his wife, but not for long could he remain in this earthly Eden, for while here the Rev. John Pickett notified the command that he had found a brigade of Yankee cavalry at the Plains, on the Manassas Gap Rail Road, and immediately the overloaded little band prepared for a night march to Manassas, making the third night of sleepless travel.

AFFAIRS AT HARPER’S FERRY – NEW YORK TIMES MONDAY SEPTEMBER 1, 1862

Harper’s Ferry Va.,

Thursday, Aug. 28 1862

Affairs in this locality are beginning to wear a decidedly warlike aspect. Troops are arriving; (another New-York regiment, One Hundred and Twenty-sixth, is just in sight,) additional guns mounting, intrenchments completed, and on every side is heard the din of preparation. Nor has this activity been in vain. Should “Stonewall,” now that he has so suddenly disappeared, turn up again here, he would certainly meet with a warm reception. Yesterday the village was filled with painful rumors to the effect that Col. MEANS’ famous company of Virginia cavalry, numbering one hundred men, had been surrounded by a large band of guerillas at Waterford, about 16 miles from here, and cut to pieces, only five escaping. The Captain, for whom Richmond authorities had offered a reward of one thousand dollars, was reported as among the prisoners. Such was the statement brought by one of the members who, being on picket duty, had escaped. All of the cavalry here were sent immediately in pursuit. Toward night, a dispatch was received from Capt. MEANS announcing that he was safe at Point of Rocks. This occasioned great joy, inasmuch as the worst fate was anticipated for him and the immense number of the company who had previously deserted from the rebel service, into which they were impressed. About 10 o’clock in the evening, our cavalry returned reporting Capt. MEAN’S men fought the rebel force until their ammunition gave out, with the loss of one killed and several wounded. None were taken prisoners. The bodies of six dead rebels were found. This was at first supposed to be a part of White’s cavalry force, but it has since been ascertained that they were bushwhackers. These “irregular fighters” are overrunning this part of the State. We hear of their operations in every direction, and during the past week they have become unusually bold. Last Friday a party of them suddenly darted into Smithfield, a small village some twelve miles from here, and captured seventeen out of twenty cavalry who were stationed here.

- Confederate Cavalry ↩︎

- The Civil War in Song and Story, 1860-1865 by Frank Moore 1865 ↩︎

- The Comanches: a history of White’s battalion, Virginia cavalry, Laurel brig., Hampton div., A.N.V., C.S.A. – Frank M. Myers Capt., 35th Va. Cavalry Pages 70-75 ↩︎

- Elijah Viers “Lige” White (August 29, 1832 – January 11, 1907) was commander of the partisan 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry during at the skirmish. His men became commonly known as “White’s Comanches” for their war cries and sudden raids on enemy targets. ↩︎

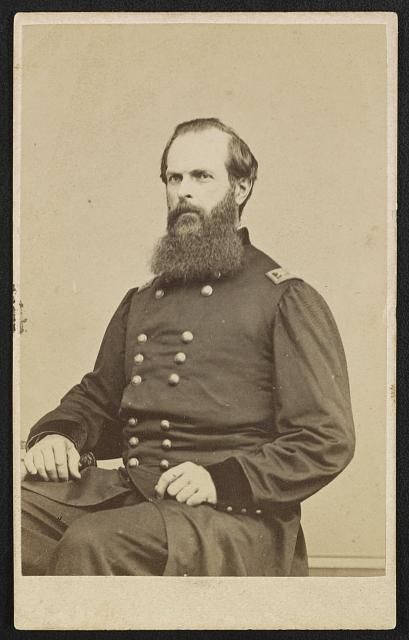

- Samuel Carrington Means (1828–1891) was the founder and first captain of the Loudoun Rangers, a Union Army unit from Virginia ↩︎

2 Comments Add yours